April 23, 2017

Posted at 9:40 pm (Pacific Time)

Most people know what a hate crime is and many are aware that the FBI publishes annual statistics on such crimes. But fewer people know that those FBI reports are legally mandated by the Hate Crimes Statistics Act (HCSA), which was signed into law 27 years ago on April 23, 1990.

Here’s a brief summary of how the HCSA came to be the law of the land.

The Historical Context for Hate Crime Laws

Up until the 1970s, violence against gay and lesbian people wasn’t widely considered a problem in the United States. Heterosexual society generally regarded acts of violence as “natural” reactions to people who were homosexual or transgressed traditional gender norms. Victims were seen as deserving whatever harassment or violence they experienced — in effect, they were “asking for it” by being visible or by simply existing.

As the modern movement for sexual minority rights developed in the 1970s, however, and gay and lesbian communities organized and attained greater visibility throughout the United States, sexual minority advocates were increasingly successful in challenging this worldview. They called upon society to reject the idea that violence was a routine consequence of being gay and instead to view antigay attacks like other instances of murder, assault, robbery, and vandalism — that is, as crimes for which blame and punishment should be directed at the perpetrators, not the victims.

In response, elected officials, policymakers, and criminal justice professionals began to address sexual orientation-based violence as a social problem. As sociologists Valerie Jenness and Ryken Grattet explained in their 2001 book, Making Hate A Crime: From Social Movement to Law Enforcement, this development built upon American society’s prior recognition that violent acts against racial, ethnic, and religious groups were repugnant in a modern democracy and warranted state intervention.

Making Hate A Crime

Such crimes came to be called hate crimes or, alternatively, bias crimes. The FBI defines a hate crime as a “criminal offense against a person or property motivated in whole or in part by an offender’s bias against a race, religion, disability, sexual orientation, ethnicity, gender, or gender identity.”

Hate crimes are not only physical attacks on the victim, they are also attacks on a core aspect of the victim’s personal identity and community membership. These components of the self are particularly important to many sexual and gender minority individuals, who experience considerable stress as a consequence of societal stigma. Being a victim of any violent crime typically has negative psychological consequences, but hate crimes are different in that they appear to inflict greater psychological trauma than other kinds of violent crime. Hate crimes also send a message of fear and intimidation to the entire sexual and gender minority community.

Historically, the modern hate crimes movement emerged relatively recently, led by the Anti-Defamation League and other organizations. Early laws, such as the statute enacted by California in 1978, restricted the definition of hate crimes to crimes motivated by the victim’s race, national origin, or religion. During the 1980s, however, many state hate crime laws were written or revised to include sexual orientation as well.

Today nearly all states have some form of hate crime law. Most of them work by enhancing penalties for hate crimes, that is, increasing the punishment for criminal acts determined to be based on the victim’s group membership. Currently, statutes in 15 states and the District of Columbia directly address crimes based on the victim’s actual or perceived sexual orientation or gender identity. In another 15 states, laws include sexual orientation but not gender identity. Of the remaining states, 15 have laws that do not list sexual orientation or gender identity as victim categories and 5 states have no hate crime law or have a law that addresses bias crimes but lists no categories and is considered too vague to enforce.

The Federal Response to Antigay Crimes

At the federal level, the first steps toward recognition of antigay hate crimes came in the 1980s. On October 9, 1986, the first-ever Congressional hearing on antigay victimization was convened by Rep. John Conyers (D-MI), chairman of the House Judiciary Committee’s Criminal Justice subcommittee. The lead witness was Kevin Berrill, director of the Anti-Violence Project of the National Gay Task Force (later the National Gay and Lesbian Task Force, or NGLTF).

Berrill is a largely unsung hero in this story. Throughout the 1980s and early 1990s, he played a central role in changing how American society viewed and responded to hate crimes against sexual and gender minorities. He worked to raise public awareness about such crimes, took the lead in documenting their occurrence, and successfully advocated for local and national responses to them in law enforcement and the criminal justice system. Berrill’s behind-the-scenes efforts — along with those of Bill Bailey, a lobbyist at the American Psychological Association (APA), and with the assistance of Reps. Barney Frank (D-MA) and Howard Berman (D-CA) — were key to bringing about the 1986 hearings.

Other subcommittee witnesses included Diana Christensen and David Wertheimer, the directors of anti-violence community groups in, respectively, San Francisco and New York, as well as representatives of criminal justice agencies, and several victims of antigay violence. I provided testimony on behalf of the American Psychological Association (APA).

The importance of documenting hate crimes based on sexual orientation was well understood by the witnesses and was noted repeatedly throughout the hearing. Afterward, therefore, it was a logical step for the participants and allied groups to direct their focus to a pending bill called the Hate Crimes Statistics Act (HCSA). Supported by the Hate Crimes Coalition (a wide range of groups promoting racial, ethnic, and religious minority rights and civil liberties), it would require the federal government to collect data on crimes based on the victim’s race, ethnicity, or religion.

I first heard about the HCSA from Tim Bellamy, an aide to Rep. Bill Green (R-NY). During a meeting with Bill Bailey and me, he suggested that expanding the Act’s purview to include sexual orientation might be a strategy for encouraging research on antigay violence.

Congressional hearings had been held for the HCSA the previous year, but it had not yet been passed. The NGLTF, APA, and other advocacy and professional groups began working to have sexual orientation included in the bill’s language. These efforts were ultimately successful.

With sexual orientation added to the bill, however, the HCSA drew strong opposition from conservative members of congress, notably Senator Jesse Helms (R-NC). Nevertheless, the Hate Crimes Coalition remained committed to keeping sexual orientation in it.

Unable to have sexual orientation removed from the Act, Senator Helms proposed an antigay amendment to it:

“It is the sense of the Senate that:

(1) the homosexual movement threatens the strength and survival of the American family as the basic unit of society;

(2) State sodomy laws should be enforced because they are in the best interest of public health;

(3) the Federal Government should not provide discrimination protections on the basis of sexual orientation; and

(4) school curriculums should not condone homosexuality as an acceptable lifestyle in American society.”

In the mid-1980s, many senators were reluctant to vote against such an amendment, fearing the fallout when they next faced reelection. Indeed, when the Senate was debating an appropriations bill not long before the HCSA, Helms had successfully attached an amendment to it prohibiting federal funding for AIDS education and prevention programs that ‘‘promote, encourage or condone homosexual activities.” Only two senators — Daniel Patrick Moynihan (D-NY) and Lowell Weicker (R-CT) — voted against that amendment.

To save the HCSA, Senators Paul Simon (D-IL) and Orrin Hatch (R-UT) proposed an alternative amendment:

SEC. 2. (a) Congress finds that-

1. the American family life is the foundation of American Society,

2. Federal policy should encourage the well-being, financial security, and health of the American family,

3. schools should not de-emphasize the critical value of American family life.

(b) Nothing in this Act shall be construed, nor shall any funds appropriated to carry out the purpose of the Act be used, to promote or encourage homosexuality.

Importantly, the Simon-Hatch Amendment came to a vote before the Helms Amendment, giving senators political cover: Voting for the Simon-Hatch amendment allowed them to take a “pro-family” stance while subsequently opposing the Helms Amendment, which was defeated 77-19.

The HCSA ultimately was passed with strong bipartisan support (the Senate vote was 92-4) and signed into law by President George H. Bush on April 23, 1990.

Hate Crime Statistics

Subsequent to the HCSA’s passage, the FBI began compiling hate crime statistics. Its first report, released in 1992, listed 4,755 hate crime offenses in 4,558 separate incidents reported to local authorities during 1991. Of those, 422 (9%) were anti-homosexual or anti-bisexual crimes.

The 1991 statistics, however, are not considered complete. The first full report was issued in 1993 and reported data for 1992. From that year through 2015 (the most recent year for which data are available), more than 27,000 incidents based on sexual orientation were reported to the FBI. In any given year, sexual orientation incidents accounted for between 11% and 23% of all bias crimes recorded by the FBI.

Congress has since passed other legislation related to hate crimes, including the 2009 Matthew Shepard and James Byrd, Jr. Hate Crimes Prevention Act, or HCPA (PL No. 111-84). It expanded federal definitions and enforcement of hate crimes, bringing crimes based on sexual orientation and gender identity under the jurisdiction of the Department of Justice (DOJ), and authorized the DOJ to assist state and local jurisdictions with investigations and prosecutions of bias-motivated crimes of violence. It also expanded the FBI’s mandate to include collection of statistics about crimes based on based on gender and gender identity.

In 2013, the FBI began reporting hate crimes based on the victim’s gender identity separately from sexual orientation crimes. That year, 31 gender identity crimes were tallied. In the 2014 and 2015 reports, the number of gender identity crimes were, respectively, 98 and 114.

Limitations of FBI Hate Crime Statistics

Although the FBI statistics are among the most definitive sources on hate crimes, they are widely believed to significantly underestimate the true incidence of sexual orientation and gender identity crimes for at least three reasons.

First, participation by local law enforcement agencies is voluntary, and even many of the local agencies that participate routinely report no occurrence of hate crimes in their jurisdiction.

Second, to be counted, hate crimes must be detected and labeled as such by local law enforcement authorities. Many agencies haven’t created the necessary procedures for such detection or lack the resources to train personnel to use them. Consequently, many incidents reported to police that might be hate crimes are never classified as such.

Third, many hate crime victims never report their experience to police authorities. While nonreporting is a problem with all crime in the United States, sexual and gender minority victims may be even less likely to report a hate crime than a nonbias crime because they fear further victimization by law enforcement personnel or they do not want their minority status to become a matter of public record

The Significance of the HCSA

Despite these limitations, passage of the HCSA was an important milestone.

It was the first federal law ever to directly address problems faced by sexual minorities, or even to include a sexual orientation provision. Gay and lesbian activists were invited to attend the signing ceremony at the White House, another historic first. And by mandating the documentation of hate crimes based on sexual orientation (and, later, gender identity), it has helped to make such crimes visible to law enforcement agencies and the public, and to make their prosecution and prevention a priority for society.

* * * * * *

I expand upon some portions of this post in my article, “Documenting Hate Crimes in the United States: Some Considerations on Data Sources,” published in the June 2017 issue (vol. 4, #2) of Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity.

Here are some resources for more information about passage of the Hate Crime Statistics Act:

Herek, G. M., & Berrill, K. T. (1992). Introduction. In G. M. Herek & K. T. Berrill (Eds.), Hate crimes: Confronting violence against lesbians and gay men (pp. 1-10). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Vaid, U. (1995). Virtual equality: The mainstreaming of gay and lesbian liberation. New York: Anchor.

Harding, R. (1990, March 27). Capitol gains: A behind-the-scenes look at the passage of the Hate Crimes Bill, The Advocate, pp. 8-10.

Copyright © 2017 by Gregory M. Herek. All rights reserved.

Permalink ·

March 24, 2017

Posted at 8:34 pm (Pacific Time)

In 1972, private consensual sexual conduct between two adults of the same sex was illegal in all but a few states. Homosexuality was officially classified as a mental illness in the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. In a national opinion survey a few years earlier, 70 percent of respondents had said they believed homosexuals were more harmful than helpful to American life. Only 1 percent believed they were more helpful than harmful. From a long list of groups named in the survey questions, only Communists and atheists were considered harmful by more respondents than homosexuals.

Against this backdrop, consider the audacity of George Weinberg, a heterosexual psychologist who published a book in 1972 titled Society and the Healthy Homosexual. Not only did Dr. Weinberg propose that homosexuals could be healthy, he also argued that a person’s mental health was impaired not by homosexuality but rather by society’s hostility toward it.

In his book’s opening sentence he asserted, “I would never consider a patient healthy unless he had overcome his prejudice against homosexuality.” Weinberg labeled that prejudice homophobia, which he defined as “the dread of being in close quarters with homosexuals — and in the case of homosexuals themselves, self-loathing.”

George Weinberg died of cancer on Monday, March 20, in Manhattan. He was 87 years old. What follows is a brief account of the origins of homophobia.

* * * * *

In his psychoanalytic training at Columbia University, Weinberg had learned the then-current view that homosexuality is a pathology and a homosexual patient’s problems — whether they occurred in personal relationships, work, or any other facet of life — ultimately stem from her or his sexual orientation.

Weinberg had known some gay people previously. And after he began practicing as a psychotherapist, some long-time friends disclosed to him that they were gay. He experienced dissonance between his professional training and his personal experience.

“I valued these friends for their encompassing, loving vision of literature, their gentleness of spirit, their subtlety,” he later wrote. “It was hard to be one of the chosen people, the ‘heteros,’ when so many people whom I admired were not invited to the party.”

It didn’t take him long to resolve the conflict. By the mid-1960s, Weinberg was an active supporter of New York’s fledgling gay movement and an opponent of psychiatric attempts to “cure” homosexuality.

The concept of homophobia came to him in 1965, around the time he gave an invited speech, titled “The Dangers of Psychoanalysis,” at the September conference of East Coast Homophile Organizations (ECHO). As he reflected on his professional colleagues’ and heterosexual friends’ strongly negative personal reactions to being around a homosexual in nonclinical settings “it came to me with utter clarity that this was a phobia.” Preparing the speech, he later said, “set me to thinking about ‘What’s wrong with those people?'”

During a 1998 interview, he told me “I found that no matter who they met or how they reacted, I could not get them to accept homosexuals in any way, and that none of them had any homosexual friends.” It occurred to him that these reactions could be described as a phobia.

Weinberg’s circle of gay friends at the time included Jack Nichols and Lige Clarke, the activists who first used homophobia in print. They wrote a weekly column, “The Homosexual Citizen,” for Screw magazine. Screw, described by one historian as a “raunchy sex tabloid,” was published in New York by Al Goldstein, and had a circulation of approximately 150,000 by mid-1969. “The Homosexual Citizen” was a first: a regular feature directed at gay readers in a widely circulated, decidedly heterosexual publication. Goldstein gave Nichols and Clarke control over the content of their columns but he composed the headlines.

Drawing from their conversations with Weinberg, Nichols and Clarke wrote about homophobia in their May 23, 1969 column, to which Goldstein assigned the headline “He-Man Horse Shit.” They used homophobia to refer to heterosexuals’ fears that others might believe they are homosexual. Such fear, they wrote, limited men’s experiences by declaring off limits such “sissified” things as poetry, art, movement, and touching. Although the Screw column appears to have been the first time homophobia appeared in print, Nichols always credited Weinberg with originating the term.

Homophobia soon achieved currency in popular speech, as evidenced by its appearance a few months later in a Time Magazine article.

Weinberg’s first published use of the word came in 1971 in a July 19th article he wrote for Gay, Nichols’ newsweekly. Titled “Words for the New Culture,” the essay foreshadowed Society and the Healthy Homosexual. In it, he described homophobia’s consequences, emphasizing its strong linkage to enforcement of male gender norms:

“The cost of any phobia is inhibition spreading to a whole circle of acts considered dangerously close to the illicit activity. In this case, acts that might be construed as invitational to homosexual feelings, or that are reminiscent of homosexual acts, are shunned. Since homosexuality is feared more in men than in women, this results in marked differences in permissiveness toward the sexes. For instance, a great many men are withheld from embracing each other or kissing each other, or longing for each other’s company, as openly as women do. It is expected that men will not see beauty in the physical forms of other men, or enjoy it, whereas women may openly express admiration for the beauty of other women. Ramifications of this phobic fear extend even to parent-child relationships. Millions of fathers feel that it would not befit them to kiss their sons affectionately or embrace them, whereas mothers can kiss and embrace their daughters as well as their sons. It is expected that men, even lifetime friends, will not sit as close together on a couch while talking earnestly as women may; they will not look into each other’s faces as steadily or as fondly.”

The essay also made it clear that Weinberg considered homophobia a form of prejudice directed by one group at another:

“When a phobia incapacitates a person from engaging in activities considered decent by society, the person himself is the sufferer. But here the phobia appears as antagonism directly toward a particular group of people. Inevitably, it leads to disdain toward the people themselves, and to mistreatment of them. The phobia in operation is a prejudice, and this means we can widen our understanding by considering the phobia from the point of view of its being a prejudice and then uncovering its motives.”

The same year that “Words for the New Culture” was published also saw the first appearance of homophobia in an academic journal. Kenneth Smith, a graduate student writing his thesis under Weinberg’s supervision, published a brief research report on its psychological correlates.

Society and the Healthy Homosexual was published the following year.

* * * * *

Homophobia neatly challenged entrenched thinking about the “problem” of homosexuality. It encapsulated the rejection, hostility, and invisibility that North American homosexual men and women had experienced throughout the twentieth century. It shifted the locus of the “problem” from gay men and lesbians to heterosexuals’ intolerance. In doing so, it questioned the legitimacy of society’s rules about gender, especially for males. The very existence of a term suggesting that rejection and hostility were not natural human reactions to homosexuality but instead were symptoms of an underlying psychological disorder subverted a central assumption of heterosexual society.

Homophobia has important limitations, at least for social and behavioral scientists. And, of course, Weinberg was not the only advocate to challenge traditional thinking about homosexuality. Society might have become sensitized to antigay prejudice without the term homophobia.

But by creating this simple, memorable label and thereby helping to define prejudice based on sexual orientation as a problem for individuals and for society, Weinberg made a profound and enduring contribution to sexual minority rights.

* * * * *

Portions of this post are based on my article Beyond “homophobia”: Thinking about sexual stigma and prejudice in the twenty-first century, published in Sexuality Research and Social Policy (2004). Other sources include:

- Ayyar, R. (2002, November 1). George Weinberg: Love is conspiratorial, deviant, and magical, Gay Today.

- Nichols, J. (1997, February 3). George Weinberg, Ph.D., Gay Today. Retrieved from

- Nichols, J. (2002). George Weinberg. In V. L. Bullough (Ed.), Before Stonewall: Activists for gay and lesbian rights in historical context (pp. 351-360). New York: Harrington Park Press.

- Weinberg, G. (1972). Society and the healthy homosexual. New York: St. Martin’s.

Copyright © 2017 by Gregory M. Herek. All rights reserved.

Permalink ·

September 1, 2016

Posted at 8:52 pm (Pacific Time)

September 2, 2016, marks the 109th birth anniversary of Dr. Evelyn Hooker, the psychologist whose pioneering research helped to establish that homosexuality is not inherently linked to mental illness. Here’s a link to an earlier post about Dr. Hooker’s life and work.

Copyright © 2016 by Gregory M. Herek. All rights reserved.

Permalink ·

June 13, 2016

Posted at 12:28 pm (Pacific Time)

In the immediate aftermath of the Pulse Nightclub shootings in Orlando, as police confirmed that Omar Mateen had shot to death at least 49 people and wounded dozens of others during his attack on the gay dance venue, law enforcement officials avoided labeling the crime an act of terrorism or a hate crime, awaiting more information.

Meanwhile, news media quoted a member of the shooter’s family saying Mateen had recently been angered when he saw two men kissing in public. Interviews with coworkers and his ex-wife revealed a history of antigay statements. And reports emerged that he had pledged his allegiance to ISIS in 911 calls before and during the attacks.

Understanding Mateen’s motives, of course, is important. But regardless of his intent, focusing solely on what went on in his mind can divert us from considering how the attack is affecting lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender people, not only in Orlando but across the country.

This attack reinforces what LGBT people already knew — that they remain stigmatized in American society and are ongoing targets for violence, harassment, and discrimination.

Social scientists sometimes refer to this knowledge — shared by minority and majority group members alike — as “felt stigma” or “perceived stigma.” The essence of felt stigma is that whether or not we condone society’s hostility toward sexual minorities, most of us know that it exists and has serious consequences.

By highlighting the phenomenon of felt stigma, I don’t intend to minimize the harm done by violent attacks to individual victims and their loved ones. In addition to inflicting physical damage, they often exact a psychological toll as well. In my own research with lesbian and gay hate crime victims, I found that they often manifest greater psychological injury after their attack than do lesbian and gay victims of comparable crimes that weren’t based on their sexual orientation. In my study, hate crime survivors tended to be more depressed, stressed, and anxious, and they felt less in control of their lives. These feelings often became linked to their gay or lesbian identity.

But the consequences of these crimes extend beyond individual targets to all members of the LGBT community, in whom they are likely to create a heightened sense of vulnerability and felt stigma. A violent attack — especially one as horrific as the Orlando shootings — serves as a reminder that LGBT people are still widely considered legitimate targets for violence and hostility, even while an increasing portion of the heterosexual population comes to accept them.

This is where hate crimes converge with terrorism. Both target a particular population, usually selecting specific victims at random. Both serve as reminders to every member of that population that they too are potential targets — they may have escaped harm for now, but might not be so lucky next time. And “next time” can come any time without warning.

This month we’ll observe the 47th anniversary of the Stonewall Rebellion, the event that is now widely commemorated as marking the beginning of the modern movement for the rights of gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgender people. June 26th is the anniversary of three historic Supreme Court decisions, one that declared state sodomy laws unconstitutional (in 2003) and two that accorded same-sex couples the right to marry (in 2013 and 2015).

In the wake of those decisions and the dramatic changes in public opinion that have accompanied them, it’s tempting to assume that stigma and prejudice targeting sexual minorities are relics of the past and are on the verge of extinction in a society that now celebrates sexual and gender diversity.

In many states, however, people can still be fired from their job for being gay. Some government officials still resist issuing marriage licenses to same-sex couples. Transgender children and teens have lately become the focus of a newly revived culture war.

Perhaps we’ll eventually know more about Omar Mateen’s motives for his murderous attack. But regardless of what we learn about him, we should remain aware of the Orlando shootings’ cultural backdrop and the fact that many LGBT people are experiencing this crime as an act of terrorism.

* * * * *

The original version of this essay appears on the Boston Globe website.

Copyright © 2016 by Gregory M. Herek. All rights reserved.

Permalink ·

September 21, 2015

Posted at 5:24 pm (Pacific Time)

As I discussed in a previous post, the mental health establishment classified homosexuality as an illness until 1973. That year, the American Psychiatric Association removed it from their Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM). The American Psychological Association soon followed suit.

The classification had always reflected value judgments and assumptions about homosexuality. There never was an empirical basis for it.

Another important event roughly coincided with the DSM change. In 1972, against the backdrop of a growing national gay rights movement, a new book was published, Society and the Healthy Homosexual. Its author, psychologist George Weinberg, began his first chapter with a provocative statement:

“I would never consider a patient healthy unless he had overcome his prejudice against homosexuality…. Even if he is heterosexual, his repugnance at homosexuality is certain to be harmful to him.”

A few pages later, Weinberg introduced a term he had coined during the late 1960s: homophobia, which he defined as heterosexuals’ “dread of being in close quarters with homosexuals” and homosexuals’ “self-loathing.”

Homophobia was a radical concept. It redirected society’s focus from what was then widely regarded as the “problem of homosexuality” to the problem of heterosexuals’ prejudice and hostility toward people who were gay. It communicated the idea that something was wrong with heterosexual people who dislike homosexuals.

To be sure, the legitimacy of anti-homosexual hostility had already been questioned by homophile activists after World War II in the United States and decades earlier in Europe. Those critiques, however, didn’t achieve widespread currency. With this new term, Weinberg gave the hostility a name and helped popularize the notion that it was a social problem that merited analysis and intervention.

The term homophobia soon became an important tool for lesbian and gay activists, advocates, and allies. Today, more than 40 years later, it’s more popular than ever.

And, in a 180-degree turn from the DSM’s classification of homosexuality, some people now argue that homophobia should be viewed as a form of mental illness.

It’s a proposal that follows logically from labeling sexual prejudice a phobia, which certainly invites people to think of it as a sickness. And it appeals to some (perhaps many) people.

But is it a good idea, one that could prove useful in eliminating prejudice against sexual minorities? Is homophobia, in fact, a form of psychopathology?

Are Homophobes Mentally Ill?

Labels and terminology can shape how we think about a phenomenon. For several reasons, I believe that embracing homophobia as a diagnostic label has negative effects on our ability to think clearly about sexual prejudice.

To begin, consider what constitutes a mental disorder. In 2001, the 4th edition of the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) provided this definition (I’ve emphasized some key phrases):

“a clinically significant behavioral or psychological syndrome or pattern that occurs in an individual and that is associated with present distress (e.g., a painful symptom) or disability (i.e., impairment in one or more important areas of functioning) or with a significantly increased risk of suffering death, pain, disability, or an important loss of freedom.“

Many — probably most — heterosexuals who harbor prejudice against sexual minorities don’t experience distress or obvious impairment from it. Nor does it put them at greater risk of death or other negative consequences.

And labeling homophobia “clinically significant” can blind us to the important fact that, in a society that still stigmatizes homosexuality, prejudice against sexual minorities isn’t a maladaptive pathology restricted to a small portion of the population. Rather, it’s part of the routine socialization that — at least until fairly recently — nearly everyone has undergone in the course of growing up.

Ironically, labeling homophobia a mental disorder has something in common with the erroneous classification of homosexuality as a sickness prior to 1973. In both cases, a diagnostic label is used to stigmatize a disliked pattern of thought and behavior. Using the label misrepresents what really is a subjective value judgment as a scientific, empirically grounded conclusion.

Moreover, by equating psychopathology with evil, it also reinforces the stigma that historically has been attached to mental illness.

Yet another problem with labeling homophobia a clinical disorder is that doing so frames heterosexuals’ hostility toward homosexuality as a purely individual phenomenon. This limits our ability to understand the social processes through which sexual prejudice develops and is reinforced. It encourages us to focus on the prejudiced individual while ignoring the larger culture that stigmatizes homosexuality.

This is not to deny that sexual prejudice (like other form of prejudice) is observed in some people with severe psychological problems. But that doesn’t mean homophobia is itself a pathology.

But What About the Newest Scientific Data?

Web and media coverage of a recently published research study by Dr. Giacomo Ciocca and his colleagues from several Italian universities could lead you to believe that we now have evidence that homophobia is linked to mental illness.

So could the study’s title, “Psychoticism, Immature Defense Mechanisms and a Fearful Attachment Style are Associated with a Higher Homophobic Attitude.”

And so could remarks by the study’s senior author, Dr. Emmanuele Jannini, who was quoted as saying “The study is opening a new research avenue, where the real disease to study is homophobia” and “we have the final proof that [homophobia] for sure is” a disease.

Published in the Journal of Sexual Medicine, the study involved administering a measure called the Homophobia Scale (HS) and several other questionnaires to a sample of Italian college students, and then assessing whether and how the scores were intercorrelated.

In brief, the researchers found that HS scores were significantly associated with scores on two checklists of psychological symptoms — “psychoticism” and “depression.” Overall, students with higher HS scores (more prejudice) tended to score higher on a Psychoticism scale, whereas students with lower HS scores (less prejudice) tended to score higher on a Depression scale.

Students with higher HS scores also tended to respond differently from low HS scorers on a questionnaire designed to reveal the types of psychological defense mechanisms a person is likely to use when experiencing anxiety. The high HS scorers tended toward a cluster of defenses that are often labeled “immature,” while the low HS students tended toward “neurotic” defenses.

Finally, when responses to another questionnaire were used to categorize students according to their attachment style — a general psychological pattern that characterizes an individual’s close relationships with others — the students classified as having a “fearful” attachment style had higher HS scores, on average, than those whose attachment style was categorized as “secure.”

A Closer Look

Many Web and media reports accepted the study’s findings at face-value. Here’s a sampling of headlines:

Examining the study’s methodology, however, makes clear that it doesn’t provide support for thinking about prejudice against lesbian, gay, and bisexual people as a disease.

Let’s begin with the sample.

The study participants were 551 psychology students, mostly female (about 71%) and Catholic (74%). The sample wasn’t representative of a larger population so there’s no way of knowing whether the findings can be generalized to anyone else.

Perhaps more importantly, none of the students could be considered mentally ill. Prior to the study, a team of clinical psychologists screened potential participants for severe psychological problems, a procedure that led to the exclusion of nine students who had been diagnosed and treated for a psychiatric disorder.

Consequently, although the students’ scores on the various psychological measures differed (as is routinely the case), the variation presumably was, as psychologists often phrase it, within normal limits.

And the sample may have included few students, if any, who would be considered “homophobic.”

Homophobia was measured using a questionnaire called the Homophobia Scale (HS), which asks respondents how much they agree or disagree with each of 25 statements such as “Gay people make me nervous” and “Homosexuality is immoral” and “Homosexual behavior should not be against the law.”

Here again, there was normal variation among the students in HS scores. But overall, the sample was very low in sexual prejudice. HS scores can range from zero to 100, with higher scores indicating greater prejudice. The average score in this study was about 26. Given that the scale consists of 25 items, a substantial portion of participants must have given a “low-prejudice” response (i.e., a 1 or 2 on a 5-point scale) to all 25 items.

So the participants weren’t mentally ill and few, if any, could be labeled homophobic.

Now let’s consider each of the study’s main findings.

Psychoticism and Depression. In addition to the HS scale, the students also completed the Symptom Check List (SCL-90), a widely used questionnaire on which respondents use a 5-point scale (ranging from Not at all to Extremely) to report how much they’ve been bothered or distressed during the previous week by each of 90 problems and complaints, e.g., “Heart pounding or racing,” “Feeling that most people cannot be trusted.”

The SCL-90 can be scored to indicate the extent to which a respondent reports symptoms and feelings that are commonly associated with various psychological problems. Here again, scores vary. Two people with different scores can both be within the “normal” range, i.e., not reporting symptoms to a degree that would warrant a clinical diagnosis.

Using a statistical procedure called multiple regression analysis, the researchers found that scores on the SCL-90 Psychoticism and Depression scales were significantly associated with Homophobia Scale scores, as noted above. This doesn’t mean that students with high HS scores were psychotic or that those with low HS scores were clinically depressed. It simply means that responses to the SCL-90 varied in a way that corresponded to variations in HS scores.

To make sense of this pattern, it’s instructive to examine the symptoms included in the SCL-90. For example, the Psychoticism scale includes “The idea that you should be punished for your sins” and “Having thoughts about sex that bother you a lot.”

It’s easy to imagine the most religious college students in this predominantly Catholic sample being more bothered than their peers by thoughts about sex and believing that they (and all people) should be punished for their sins.

Highly religious students are also more likely than others to score high on the HS scale. Many empirical studies (including my own) have shown that conservative religious beliefs are strongly associated with higher levels of sexual prejudice.

Thus, there’s ample reason — having nothing to do with psychoticism — to expect that students with higher HS scores would also report more distress from thoughts about sex and sin. Responses to these two SCL-90 items alone may well account for the correlation observed between HS and Psychoticism scores. Unfortunately, the researchers’ statistical analysis didn’t take differences in religious belief into account.

Defense Mechanisms. The concept of defense mechanisms derives mainly from psychoanalytic theory, which posits that they are unconscious strategies for avoiding anxiety. Psychoanalysts have developed a long list of them which includes, for example, projection and reaction formation.

In the extreme, they can be associated with psychopathology. Most of them, however, are also used by psychologically healthy people, at least occasionally.

Students in the Ciocca et al. study completed the Defense Style Questionnaire (DSQ), which consists of 40 statements, each of which is intended to indicate a tendency to use one of 20 different defenses. For example, agreeing that “People tend to mistreat me” is supposed to indicate a tendency to use projection. Agreeing that “If someone mugged me and stole my money, I’d rather he be helped than punished” is supposed to be consistent with using reaction formation.

Of course, there are many reasons — having nothing to do with defense — why a person might agree with one or more of these statements.

DSQ scores for individual defenses can be combined into larger categories. Using one of the most common categorization systems, the researchers found that students with higher HS scores tended to score somewhat higher on “immature” defenses (a group that includes projection), while low HS scorers tended to score higher on “neurotic” defenses (which includes reaction formation). In this system, using neurotic defenses to excess is considered less pathological than using immature defenses.

As noted above, however, most of the defenses are used by mentally healthy people (like the students in this sample). Minor variations within a healthy group don’t indicate pathology.

Attachment. Finally, the researchers categorized students according to their predominant attachment style, as assessed by the Relationships Questionnaire (RQ). Respondents to the RQ rate the extent to which their own patterns of relating to others correspond to each of four descriptions.

In the Ciocca et al. study, students in one attachment category (“Fearful”) scored significantly higher on the Homophobia Scale than students in another category (“Secure”). HS scores for students in the other two attachment categories (“Preoccupied” and “Dismissing”) didn’t differ significantly from each other or from the Fearful or Secure groups.

For at least three reasons, no conclusions about homophobia and mental illness can be drawn from this finding.

First, the Relationships Questionnaire isn’t a measure of psychopathology. Mentally healthy people can (and do) occupy any of the four categories.

Second, some research has suggested that high levels of attachment anxiety may be linked to derogation of all outgroups. So the findings of Ciocci et al. may reflect this more general tendency.

Third, results from other published studies that have looked for links between attachment style and homophobia have been inconsistent and contradictory. Like Ciocca et al., none of these studies used a representative sample. The safest conclusion to draw about homophobia and attachment style is that the jury is still out.

Beyond Homophobia

In summary, the Ciocca et al., study doesn’t provide evidence that would justify categorizing homophobia as a mental illness. Nor does any other empirical research.

Labeling homophobia a form of psychopathology may score rhetorical points but is inaccurate. And doing so distracts us from achieving a better understanding of the phenomena encompassed by the term homophobia.

As readers of my empirical and theoretical papers know, I’ve been arguing for much of my professional career that scientific research must move beyond homophobia in order to yield insights about cultural stigma and individual prejudice based on sexual orientation.

To facilitate that shift, I’ve developed a conceptual framework for thinking about and studying these phenomena.

I’ll discuss that framework and relevant empirical research in future posts.

Copyright © 2015 by Gregory M. Herek. All rights reserved.

Permalink ·

June 17, 2015

Posted at 2:00 pm (Pacific Time)

Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsberg has been quoted as saying the Court’s 1973 Roe v. Wade decision went “too far, too fast.”

Her comment has sometimes been cited in speculation that the Court won’t rule that people have a constitutional right to marry a same-sex partner because the Justices are reluctant to get too far ahead of public opinion.

However, public opinion may be well ahead of the Court in this arena. As we await a ruling in the Orbergefell marriage equality cases, it’s a good time to reflect on current public sentiment about marriage rights for same-sex couples, and how and why it has shifted over the last two decades.

Public Opinion Today

Last week, the Pew Research Center reported that 57% of the respondents in their latest national survey (most of whom presumably were heterosexual) said they support “allowing gays and lesbians to marry legally.” Only 39% were opposed.

Compare this to a 2001 Pew poll in which the numbers were reversed: 57% opposed marriage equality and only 35% supported it.

A recent Gallup poll showed the same remarkable turnaround: 60% of their respondents now endorse the statement that “marriages between same-sex couples should be recognized by the law as valid, with the same rights as traditional marriage.”

As with the Pew data, earlier Gallup surveys revealed a quite different pattern. In 2005, 59% opposed marriage equality and only 37% supported it. Still earlier, in 1996, marriage rights for same-sex couples were opposed by more than two thirds (68%) of Gallup respondents, with only 27% in support.

Polling data on marriage equality have been somewhat confusing because different surveys have yielded different numbers. As early as 2010, a few already showed a majority of Americans favoring marriage equality. And even today some still show less than half of the public supporting marriage equality.

This variability is largely explained by methodological differences among the polling organizations, according to a meta-analysis by UCLA political scientist Andrew Flores that was recently published in Public Opinion Quarterly.

When Dr. Flores combined the data from more than 130 different polls, controlling statistically for variations in question wording and “house effects” (i.e., differences among polling organizations in how they collect and analyze their data), he found a clear trend: Support for marriage equality has increased fairly steadily since 1996, with a majority of the public endorsing it by 2014.

The trend of shifting attitudes isn’t limited to marriage equality. We see it as well in public opinion about adoption rights, the ability of same-sex couples to be good parents, protection from employment discrimination, and other issues relevant to law and policy. And it is also evidenced by a steady increase in favorable attitudes toward lesbian and gay people in recent years. (Attitudes toward bisexual women and men have probably changed as well, but few polls have included questions designed to specifically tap those attitudes.)

Change has occurred in nearly every demographic group, although it’s more evident in some groups than in others. For example, marriage equality support has increased more among Democrats and Independents than Republicans. But Republicans’ support has nevertheless been increasing as well.

Is the Shift Generational or Individual?

How can we explain these seismic shifts over a relatively brief time span?

They’re often attributed to ongoing population turnover. According to this explanation, individuals aren’t changing their opinions. Rather, change results from older generations dying out and younger ones taking their place. On average, older people are less likely than their younger counterparts to support marriage equality or express favorable attitudes toward sexual minorities. As time passes and younger generations come of age, their attitudes become more dominant in society as a whole.

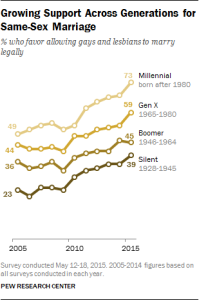

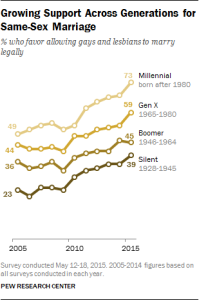

This pattern of generational replacement is evident when polling data are broken down by age groups. As shown in the Pew data, for example, support for marriage equality is lowest among adults born during the Depression Era but increases steadily in each successive generation. Baby Boomers are more supportive than their elders, GenXers are more supportive than Boomers, and Milliennials show the strongest support of any age group.

But generational replacement is only part of the story. The Pew graph shows that opinions have also been shifting within each age group. In other words, attitude change isn’t happening only in the population as a whole; heterosexual individuals have been changing their minds about sexual minorities, and at a rapid pace.

In fact, individual change is the primary force behind the big shifts in public opinion. When researchers Gregory Lewis and Lanae Hatalsky combined data from more than 128,000 respondents in nearly 100 national surveys conducted between 2004 and 2011, they found that only 25% of the shift in overall support for marriage equality during those 8 years could be attributed to generational replacement. Most of the change – 75% of it – resulted from individuals who once opposed or were undecided about marriage equality coming to support it.

Why Are People Changing Their Minds?

Why have so many individual Americans changed their minds? There’s no single answer to this question; people have different reasons. But we can see a common thread running through those reasons if we assume that people generally adopt attitudes and opinions to meet their important psychological needs and to feel good about themselves. When any particular attitude stops serving these purposes, it’s susceptible to change.

For example, heterosexual people whose sense of self is grounded mainly in their personal value system – whether deriving from religion, politics, ethics, or other sources – are likely to express attitudes that serve to affirm those values. Whether they support or oppose marriage equality, their attitude functions to solidify their sense of personal identity and increase their feelings of self-worth. If they come to see their stance on marriage equality as inconsistent with key aspects of their value system, however, they may be open to change.

A 2013 Pew survey, for example, found that 28% of those who endorsed marriage equality said they hadn’t always held that view. When asked what made them change their minds, roughly one third cited values — e.g., their own moral and religious beliefs or their support for equality. For them, being true to those values came to mean expressing support for marriage equality.

Other heterosexual people have especially strong needs for social acceptance and affiliation. The main motivation underlying their marriage equality opinions is their desire to secure approval and support from friends, family, and other important groups. If group norms change, however, clinging to the old attitude may block them from meeting those affiliation needs. As support for marriage equality increasingly becomes the norm throughout much of the United States, people seeking their group’s approval are more and more likely to get it by changing their attitudes to conform with the trend.

About one sixth of respondents in the 2013 Pew survey attributed their new-found endorsement of marriage equality to their perception that social acceptance of it is inevitable. For at least some of them, changing their attitudes may have allowed them to continue to enjoy group acceptance in a changing world.

Attitudes can also function to help people make sense of their own past experiences, including their interactions with people from groups other than their own. Having an unpleasant encounter with a lesbian, gay, or bisexual person may lead heterosexuals to hold negative feelings toward all sexual minorities. Conversely, good experiences can generalize to a positive attitude toward the entire group and issues that affect it.

Interestingly, it turns out that heterosexuals’ personal contact with lesbian, gay, or bisexual people usually results in more positive attitudes, not only toward the specific person involved, but also toward sexual minorities as a group. Having a friend or relative who is gay, lesbian, or bisexual can be a potent motivator for heterosexuals to change their opinions.

We see evidence of this pattern in the 2013 Pew poll. About one third of the participants who had come to support marriage equality cited their personal experiences with gay or lesbian friends, family members, or acquaintances as the reason why.

As I’ve discussed in previous blog posts, personal contact appears to be especially influential when it includes open discussion of what it’s like to be lesbian, gay, or bisexual. Such discussions can lead heterosexuals to think about sexual minorities in a new way and to rethink the connections between their personal values and their attitudes toward sexual minorities. And when heterosexuals see that their own family or friendship circle includes sexual minorities, the desire to maintain their social ties can motivate them to rethink their attitudes.

The functional approach I’ve used to organize this discussion focuses on individual psychology. But shifts in public opinion about marriage equality aren’t simply a matter of what goes on inside people’s heads. The larger culture’s beliefs and norms make possible the relationship between particular attitudes and specific psychological needs. As cultural institutions have changed in recent years, so have the ways in which heterosexuals’ attitudes toward marriage equality and sexual minorities are linked to their values, worldview, group memberships, and personal relationships. (For a more sociological perspective on attitude change, see this post from The Conversation.com.)

Back to Justice Ginsburg

Perhaps another quotation from Justice Ginsburg is more fitting to the current moment than her “too far, too fast” comment.

Earlier this week, she displayed a clear understanding of how and why public attitudes toward lesbian, gay, and bisexual people have changed when she cited the power of personal contact and coming out in advancing sexual minority rights:

“People looked around … and it was my next-door neighbor, of whom I was very fond, my child’s best friend, even my child…. They are people we know and we love and we respect, and they are part of us…. Discrimination began to break down very rapidly once they no longer hid in a corner or in a closet.”

If, as many observers expect, she and a majority of her colleagues on the Court affirm same-sex couples’ right to marry, they won’t be getting ahead of public opinion. Rather, they’ll be following the lead of the American people.

Copyright © 2015 by Gregory M. Herek. All rights reserved.

Permalink ·

February 3, 2015

Posted at 12:01 pm (Pacific Time)

Not so long ago, homosexuality was triply stigmatized.

Throughout much of the 20th century, in addition to being condemned as a sin and prosecuted as a crime, it was assumed by the mental health professions to be an illness.

Although that assumption was never based on valid scientific research, the stigma attached to homosexuality impelled untold numbers of lesbian, gay, and bisexual people to seek a cure for their condition. Others were coerced into treatment after being arrested or hospitalized.

Psychologists and psychiatrists used a variety of techniques on them, ranging from talk therapy to electroshock, aversive conditioning, lobotomies, hormone injections, hysterectomies, and castrations.

None were effective.

Meanwhile, new research was challenging orthodox beliefs about homosexuality and prompting some mental health professionals and researchers to question the validity of the sickness model.

Alfred Kinsey’s studies revealed that same-sex attraction and behavior were much more common than had been widely believed. Clellan Ford and Frank Beach showed that homosexual behavior was common across human societies and in other species.

And Evelyn Hooker documented the existence of well-adjusted gay men. She also demonstrated that experts in the “diagnosis” of homosexuality could not distinguish between the Rorschach protocols of well-functioning gay and heterosexual men at a level better than chance.

The larger society was also changing. By the 1960s, gay and lesbian activists were challenging the notion that they were mentally ill.

Psychiatric and psychological orthodoxy proved unable to withstand the critical scrutiny that these developments brought. On December 15, 1973, millions of people suddenly found themselves free of mental illness when the American Psychiatric Association’s Board of Directors voted to remove homosexuality as a diagnosis from its Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM).

It was arguably the biggest mass cure in the modern history of mental health.

Then, meeting in late January of 1975 – almost exactly 40 years ago – the American Psychological Association (APA) Council of Representatives voted to support the psychiatrists’ action, affirming that:

“Homosexuality per se implies no impairment in judgment, stability, reliability, or general social and vocational capabilities.”

This complete reversal in the status accorded to homosexuality by the mental health profession’s two largest and most influential organizations was to have a huge impact.

Gay, lesbian, and bisexual people would no longer have to grow up assuming they are sick. Reputable psychologists and psychiatrists would no longer tell them they can and should become heterosexual. Because a characteristic that isn’t an illness doesn’t need treatment, the raison d’etre for attempting to cure homosexuality vanished.

Nearly all therapists eventually abandoned their efforts to make gay people straight. New therapeutic approaches were developed that affirm the value of gay, lesbian, and bisexual identities and same-sex relationships while assisting sexual minorities in coping with the challenges created by societal stigma. These approaches are now integral to the education, training, and practice of psychologists and other mental health professionals.

*Â Â Â Â *Â Â Â Â *Â Â Â Â *Â Â Â Â *

But the significance of this year’s 40th anniversary extends further. The APA’s 1975 resolution also urged mental health professionals

“to take the lead in removing the stigma of mental illness that has long been associated with homosexual orientations.”

Thus, the Association committed itself to advocacy, lobbying, and educational efforts on behalf of sexual minorities. It has since followed through by promoting research and communicating scientific and clinical knowledge about sexual orientation to the courts, elected officials, policy makers, educators, and the general public.

Notably, these efforts have included filing amicus briefs in more than 40 major federal and state court cases involving the rights of sexual minorities. Roughly half of those cases involved legal recognition of same-sex couples. Others addressed state sodomy laws, discrimination, restrictions on military service, parenting rights, and related issues.

Drawing from empirical research, the APA briefs have explained important facts about sexual orientation:

*Â Â Â Â *Â Â Â Â *Â Â Â Â *Â Â Â Â *

In April, when the U.S. Supreme Court hears oral arguments for four marriage equality cases, the APA will file another amicus brief summarizing current scientific knowledge and professional opinion about sexual orientation, committed intimate relationships, parenting, and related topics.

In doing so, the Association will continue to honor its pledge to take the lead in “removing the stigma.”

*Â Â Â Â *Â Â Â Â *Â Â Â Â *Â Â Â Â *

A version of this post also appears on the APA’s blog, Psychology Benefits Society.

The APA amicus briefs are available at: http://www.apa.org/about/offices/ogc/amicus/index-issues.aspx

Copyright © 2015 by Gregory M. Herek. All rights reserved.

Permalink ·

« Previous entries Next Page » Next Page »