June 26, 2009

Posted at 12:15 am (Pacific Time)

President Obama is under increasing pressure to begin dismantling the military’s “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” policy.

Last month the Palm Center at the University of California, Santa Barbara, released a new report showing how the President can legally suspend discharges of gay and lesbian personnel in advance of congressional action to permanently repeal DADT. (Full disclosure: I’m a coauthor of that report; my main contribution was to the section on how to effectively implement a new, nondiscriminatory policy.)

Earlier this week, 77 members of Congress sent an open letter to the President, urging him to suspend investigations and discharges of service members in the Armed Forces because of their sexual orientation. “By taking leadership of the important issue of Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell,” said Rep. Alcee Hastings (D-FL), “President Obama would allow openly gay and lesbian service members to continue serving their country and send a clear signal to Congress to initiate the legislative repeal process.”

And Wednesday, the Center for American Progress issued a five-step plan for repealing DADT that begins with an executive order suspending discharges.

What would be the political costs for the President and Congress of eliminating DADT?

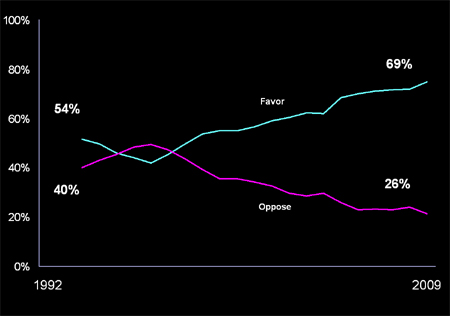

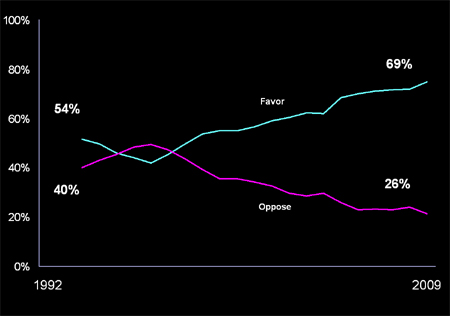

In terms of public approval, not much. In fact, repealing the policy might score points with voters. Poll data indicate that opposition to DADT has been steadily increasing in the years since it was first enacted, and that Americans now solidly support getting rid of it.

Public Opinion About DADT: Then and Now

Just before the 1992 Presidential election, by a margin of 54% to 40%, respondents to a national Harris survey supported “allowing gays and lesbians to serve in the military.” But the following year, as public debate about military policy took center stage, most polls showed public opposition to gay service members. (Also in 1993, pollsters began asking about service by openly gay and lesbian personnel.)

By 1994, however, after DADT had been enacted, public opinion again began to shift and a growing majority wanted to allow openly gay people to serve. As shown in the graph, this trend has continued to the present day. In the most recent poll – conducted last month by Gallup – 69% favored allowing openly gay people to serve. Only 26% were opposed.

This graph only includes polls that asked “Do you favor or oppose allowing openly gay men and lesbian women to serve in the military?” (or used similar wording). Other surveys that asked the question in different ways have obtained similar results.

In some surveys over the years, for example, the question about military service has been posed in terms of equal employment opportunities. With the question framed this way, the public has been even more likely to endorse military service by gay and lesbian personnel. As early as 1977, 51% of Gallup respondents said gay people “should be hired” for the armed forces, and that majority grew steadily over time. By 2005 (the last instance I could find when this question was posed in a national poll), 79% favored having the armed forces “hire” gay men and lesbians, while only 19% opposed it.

Other surveys have asked respondents to select from among three options: (a) allowing gay men and lesbians to serve openly, (b) allowing them to serve but without openly acknowledging their sexual orientation (the DADT approach), or (c) banning them entirely from military service. Over the past 15 years, relatively few respondents have advocated completely banning gay people from the military – never more than roughly 1 in 5. In July, 2007 (the most recent poll that asked this version of the question), only 15% said they wanted a total ban on gay personnel. In that same poll, 36% endorsed the DADT approach, whereas a plurality of 46% favored allowing gay people to serve openly. Compared to a similar poll in 2000, the 2007 results represented an increase of 6 points in favor of openly gay personnel, and a decrease of 7 points in support of a total ban.

Thus, regardless of how the question is asked, the long-term trend has been toward increasing support for openly gay service members.

The Unit Cohesion Argument: The Public Isn’t Buying It

Americans also have grown skeptical of the main rationale that has been offered for retaining DADT. In a 1993 Gallup/CNN/USA Today poll conducted shortly after Bill Clinton’s inauguration, 51% agreed that “admitting gays to the military would undermine discipline and morale” (46% disagreed).

But in a Quinnipiac University national poll this April, 58% disagreed that “allowing openly gay men and women to serve in the military would be divisive for the troops and hurt their ability to fight effectively.” In that same poll, a solid 56% favored repealing DADT whereas only 37% said it shouldn’t be repealed.

Support For A New Policy Is Broad-Based

A striking feature of the May 2009 Gallup poll is the breadth of support it reveals for a new military policy. Not surprisingly, self-described liberals are almost unanimous in supporting a nondiscriminatory policy (86%). But a solid majority of conservatives — 58% — also support openly gay and lesbian service members, as do 58% of Republicans and 60% of those who attend religious services weekly. Support has increased substantially in these groups since Gallup asked the same question in 2004 — by 6 points among Republicans, 11 points among regular churchgoers, and 12 points among conservatives.

Support is even higher among Democrats, Independents, and the less religious. And openly gay service members have solid support among both men and women, in all regions of the US (including 57% in the South), and in all age groups (even among those who are over 65, of whom 60% support a new policy).

The Bottom Line

This is a policy area in which the public is ahead of Congress and the President. There will certainly be an outcry from some far Right groups when President Obama suspends DADT and Congress overturns it permanently. In contrast to 1993, however, there appears to be a solid base of public support for a new policy that allows lesbian and gay Americans to serve their country without having to lie about who they are.

*Â Â Â Â *Â Â Â Â *Â Â Â Â *Â Â Â Â *

A slightly different version of this post appears on the Palm Center’s blog, Blueprints.

Copyright © 2009 by Gregory M. Herek. All rights reserved.

Permalink ·

July 23, 2008

Posted at 11:02 am (Pacific Time)

Today the Military Personnel Subcommittee of the House Armed Services Committee holds hearings on “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell.”

The congressional hearings come as Democrats increasingly discuss repealing the policy under a new Administration, and in the wake of a July ABC News/Washington Post Poll in which 75% of respondents said that “homosexuals who DO publicly disclose their sexual orientation should be allowed to serve in the military.” (78% said those who DON’T disclose their sexual orientation should be allowed to serve.)

The hearings also follow the recent release of a report by a team of retired senior military officers that concluded the ban on openly gay service members is counterproductive and should end, as well as a public statement signed by more than 50 retired generals and admirals that calls on Congress to repeal DADT.

With these signs of quickening movement toward eliminating the military’s discriminatory personnel policy, I’d like to be able to discuss the social science research relevant to the policy.

However, there isn’t much to say that is new.

Revisiting the Social Science Data

To be sure, new studies have been released that consider issues related to privacy, unit cohesion, and the experiences of other countries that have integrated sexual minorities into their militaries. I’ve discussed some of this work in previous posts. The Michael D. Palm Center website at the University of California, Santa Barbara, is also an excellent resource for such research.

But the conclusions of the newer research don’t differ much from those of past studies.

Thus, it seems appropriate to revisit a previous set of hearings in which the House Armed Services Committee heard about social science research relevant to military personnel policy. They were held in May of 1993 and were chaired by Rep. Ron Dellums (D-CA).

I was invited to testify before the Committee on behalf of the American Psychological Association and five other professional organizations (the American Psychiatric Association, the National Association of Social Workers, the American Counseling Association, the American Nursing Association, and the Sex Information and Education Council of the United States).

What follows is the bulk of my oral statement (with some introductory and background material omitted):

Mr. Chairman and members of the Committee, I am pleased to have the opportunity to appear before you today to provide testimony on the policy implications of lifting the ban on homosexuals in the military….

My written testimony to the Committee summarizes the results of an extensive review of the relevant published research from the social and behavioral sciences. That review is lengthy. However, I can summarize its conclusions in a few words: The research data show that there is nothing about lesbians and gay men that makes them inherently unfit for military service, and there is nothing about heterosexuals that makes them inherently unable to work and live with gay people in close quarters.

….I would like to address two questions that have been raised repeatedly in the current discussion surrounding the military ban on service by gay men and lesbians. The first question is whether lesbians and gay men are inherently unfit for service. In the current debate, some consensus seems to have been reached that gay people are just as competent, just as dedicated, and just as patriotic as their heterosexual counterparts. However, questions still are raised concerning whether the presence of openly gay military personnel would create a heightened risk for sexual harassment, favoritism, or fraternization.

Obviously, data are not available to address these questions directly because the current policy has made collection of such data impossible in the military. However, based on research conducted with civilians, as well as reports from quasi-military organizations in the United States (such as police and fire departments) and the armed forces of other countries, there is no reason to expect that gay men and lesbians would be any more likely than heterosexuals to engage in sexual harassment or other prohibited conduct. We know that a homosexual orientation is not associated with impaired psychological functioning; it is not in any way a mental illness. In addition, there is no valid scientific evidence to indicate that gay men and lesbians are less able than heterosexuals to control their sexual or romantic urges, to refrain from the abuse of power, to obey rules and laws, to interact effectively with others, or to exercise good judgment in handling authority….

The second question I would like to address is whether unit cohesion and morale would be harmed if personnel known to be gay were allowed to serve. Would heterosexual personnel refuse to work and live in close quarters with lesbian or gay male service members? This question reflects a recognition that stigma leads many heterosexuals to hold false stereotypes about lesbians and gay men and unwarranted prejudices against them.

As with the first question, we do not currently have data that directly answer questions about morale and cohesion. We do know, however, that heterosexuals are fully capable of establishing close interpersonal relationships with gay people and that as many as one-third of the adult heterosexual population in the U.S. has already done so. We also know that heterosexuals who have a close ongoing relationship with a gay man or a lesbian tend to express favorable and accepting attitudes toward gay people as a group. And it appears that ongoing interpersonal contact in a supportive environment where common goals are emphasized, and prejudice is clearly unacceptable, is likely to foster positive feelings toward gay men and lesbians. Thus, the assumption that heterosexuals cannot overcome their prejudices toward gay people is a mistaken one.

In summary, neither heterosexuals nor homosexuals appear to possess any characteristics that would make them inherently incapable of functioning under a nondiscriminatory military policy. In my written testimony, I have offered a number of recommendations for implementing such a policy. I would like to mention five of the principal recommendations here.

The military should:

- establish clear norms that sexual orientation is irrelevant to performing one’s duty and that everyone should be judged on her or his own merits;

- eliminate false stereotypes about gay men and lesbians through education and sensitivity training for all personnel;

- set uniform standards for public conduct that apply equally to heterosexual and homosexual personnel;

- deal with sexual harassment as a form of conduct rather than as a characteristic of a class of people, and establish that all sexual harassment is unacceptable regardless of the genders or sexual orientations involved;

- take a firm and highly publicized stand that violence against gay personnel is unacceptable and will be punished quickly and severely; attach stiff penalties to antigay violence perpetrated by military personnel.

Undoubtedly, implementing a new policy will involve challenges that will require careful and planned responses from the military leadership. This has been true for racial and gender integration, and it will be true for integration of open lesbians and gay men. The important point is that such challenges can be successfully met. The real question for debate is whether the military, the government, and the country as a whole are willing to meet them.

Mr. Chairman, thank you for the opportunity to testify today. I will be happy to answer any questions that members of the Committee might have.

From 1993 to 2008

That was in 1993. Today, as then, the real question is not whether sexual minorities can be successfully integrated into the military. The social science data answered this question in the affirmative then, and do so even more clearly now.

Rather, the issue is whether the United States is willing to repudiate its current practice of antigay discrimination and address the challenges associated with a new policy.

The growing opposition to DADT among military veterans and the public indicate that we finally may be ready to take up this challenge.

*Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â *Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â *Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â *Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â *

The full text of my 1993 oral statement before the House Armed Services Committee can be read on my website.

Copyright © 2008 by Gregory M. Herek. All rights reserved.

Permalink ·

June 21, 2008

Posted at 12:53 pm (Pacific Time)

On Thursday, President Bush awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom to General Peter Pace, the former Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, “for his steadfast leadership, his selfless devotion to keeping Americans safe, and his great courage.”

On Thursday, President Bush awarded the Presidential Medal of Freedom to General Peter Pace, the former Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, “for his steadfast leadership, his selfless devotion to keeping Americans safe, and his great courage.”

The award was greeted with widespread criticism because of remarks made by Gen. Pace last year about homosexuality and the “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” (DADT) policy.

In a March 12, 2007, interview with the Chicago Tribune, he likened homosexuality to adultery and asserted, “I believe homosexual acts between two individuals are immoral and that we should not condone immoral acts…. I do not believe the United States is well served by a policy that says it is okay to be immoral in any way.”

His remarks sparked outrage among congressional Democrats and gay advocacy groups. According to a National Public Radio report, senior Pentagon officials privately disclosed that the Secretary of Defense summoned Pace to his office after the comments were made public and demanded that he issue a statement. The following day, the Pentagon released the General’s statement, in which he downplayed the importance of his own moral views, but did not apologize for his remarks:

I made two points in support of the policy during the interview. One, “Don’t Ask Don’t Tell” allows individuals to serve this nation; and two, it does not make a judgment about the morality of individual acts. In expressing my support for the current policy, I also offered some personal opinions about moral conduct. I should have focused more on my support of the policy and less on my personal moral views.

Six months later, shortly before retiring, Gen. Pace reiterated his sentiments at a September Senate Appropriations Committee hearing. Saying he sought to clarify his earlier remarks, Pace noted that there are “wonderful Americans who happen to be homosexual serving in the military.” He continued:

We need to be very precise then, about what I said wearing my stars and being very conscious of it…. And that is, very simply, that we should respect those who want to serve the nation but not through the law of the land, condone activity that, in my upbringing, is counter to God’s law.

*Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â *Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â *Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â *Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â *

In response to Pres. Bush’s decision to award Gen. Pace with Presidential Medal of Freedom this week, Aubrey Sarvis, Executive Director of the Servicemembers’ Legal Defense Network (SLDN) said:

Honoring General Pace with the country’s highest civilian award is outrageous, insensitive and disrespectful to the 65,000 lesbian and gay troops currently serving on active duty in the armed forces. Our men and women in uniform are making tremendous sacrifices for our country and are looking for the President to recognize leaders who offer them praise and vision, not condemnation and scorn.

Mr. Sarvis makes a valid point, but perhaps we should actually be grateful to Gen. Pace. After all, most previous attempts to defend DADT have tried to justify the policy with spurious claims — for example:

- that the presence of openly gay and lesbian military personnel would damage unit cohesion and impair the military’s ability to complete its mission

- that sharing living quarters with gay and lesbian personnel would intrude unacceptably on the privacy of heterosexual personnel

- that allowing sexual minority personnel to serve openly would damage the military’s reputation and reduce reenlistment rates.

However, empirical research has consistently failed to support these assertions. A few examples:

- A 2006 Zogby poll conducted with active-duty personnel and veterans indicated that DADT isn’t strongly supported by combat personnel and veterans, and that allowing openly gay and lesbian personnel to serve is unlikely to reduce reenlistment or impair future recruitment. In addition, the poll showed that many military personnel know or suspect that their unit includes gay or lesbian members, and that most of those who knew for certain that their unit included one or more gay members did not believe that the latter’s presence affected either the respondent’s personal morale or the morale of the unit. Based on these and other data, Prof. Belkin argues in a paper recently published in Armed Forces & Society that the policy actually harms the military’s reputation.

*Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â *Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â *Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â *Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â *

Rather than trying to justify DADT on bogus factual grounds, Gen. Pace gave the world a refreshingly honest account of the real reasons why the US government still clings to the policy. By highlighting the moral worldview on which it is based, he showed that the policy is mainly about religious beliefs and longstanding prejudices, not the laundry list of concerns about the practical impact of a policy change that are routinely cited by DADT defenders.

Of course, it may not have been Gen. Pace’s intention to provide such clarity about the real roots of DADT. But perhaps he nevertheless deserves recognition for it.

And, since past Medal of Freedom awardees from within the Bush administration have included former CIA Director George Tenet, former Iraq administrator L. Paul Bremer, and Gen. Tommy Franks — all of whom have been strongly criticized for their roles in the current Administration’s early Iraq decisionmaking and policies — perhaps Gen. Pace is in the right company.

*Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â *Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â *Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â *Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â *

For further discussions of social science research relevant to DADT, consult the “Publications” page on the Michael D. Palm Center website at the University of California, Santa Barbara

For more information about DADT, consult the Servicemembers’ Legal Defense Network website.

Copyright © 2008 by Gregory M. Herek. All rights reserved.

Permalink ·

June 12, 2008

Posted at 4:33 pm (Pacific Time)

On Wednesday, Norway’s Parliament voted 84-41 to make that country’s marriage law gender-neutral, thereby granting same-sex couples the right to marry and to adopt children on an equal basis with heterosexual couples. The new law will also allow the Church of Norway to bless same-sex marriages, although each congregation may be permitted to decide for itself whether to conduct weddings for gay and lesbian couples.

Norway thus becomes the world’s sixth nation to grant marriage equality to same-sex couples, joining the Netherlands, Belgium, Spain, Canada, and South Africa.

With the exception of South Africa, all of those countries are members of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO). The Norwegian Parliament’s vote is the most recent sign of the widening gap between the United States and its NATO allies on national policies concerning human rights for sexual minorities, exemplified by laws concerning committed relationships and military service.

In addition to the 5 countries with marriage equality, 9 other NATO member countries allow same-sex couples to register their partnerships and thereby enjoy many of the same rights and obligations as married couples — the United Kingdom, France, Germany, Slovenia, the Czech Republic, Denmark, Hungary, Iceland, and Luxembourg. And Portugal recognizes unregistered cohabitation, which gives same-sex couples some of the limited rights (excluding joint adoption) enjoyed by different-sex couples living in a de facto union for more than two years.

Most of the NATO members that recognize marriage or same-sex registered partnerships also permit military service by gay people. In addition, some NATO countries that don’t recognize same-sex relationships nevertheless permit gay personnel to serve in their military. Estonia, Italy, and Lithuania are in this group.

[Note: Greece bans gay officers but permits gay enlisted conscripts, and Portugal has no formal ban on gay personnel but may screen out homosexuals during the induction process. As Profs. Aaron Belkin and Melissa Sheridan Embser-Herbert point out in a recent review of international military policies, “Because of the range of policies, it is, indeed, a complex task to track the status of regulations and customs concerning gays and lesbians in the armed forces around the world.” Thus, “it is incredibly labor intensive to determine with great accuracy what a country permits or prohibits by law and what really happens on a day-to-day basis. Not only do laws change, but the application of the law may vary from one location to another.”]

Some NATO countries neither recognize same-sex relationships nor permit military service by sexual minorities. They include Bulgaria, Latvia, Poland, Romania, and Turkey.

And, of course, the United States.

Our federal Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA) expressly prohibits the federal government from recognizing legal marriages or civil unions between same-sex couples. And our military policy (known as “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” or DADT), while ostensibly allowing gay and lesbian personnel to serve in secrecy, has resulted in widespread antigay harassment and discharge of sexual minorities. This has continued even as the military has lowered its standards in order to meet enlistment goals — for example, by granting “moral waivers” to convicted felons and recruiting individuals lacking a high school diploma.

Social science research has failed to support the premises on which DADT is based, and opinion polls generally indicate that the US public favors allowing sexual minority military personnel to serve openly. Even onetime supporters of DADT have recognized that it hasn’t worked. Former Senator Sam Nunn and the late Charles Moskos both expressed second thoughts about the policy’s implementation. Gen. John M. Shalikashvili, chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff when DADT was adopted, now argues for its repeal.

And, while a majority of the US public still opposes marriage equality, most American adults favor some form of legal recognition for same-sex couples.

Yet, Congress has shown little willingness to change current laws. In an Associated Press story today, Anne Flaherty reported that congressional Democrats have been reluctant to push a legislative repeal of the DADT law, citing resistance from their more conservative members and the inevitability of a veto by President Bush. There are no immediate prospects for Congress to repeal DOMA.

All of this might change if Barack Obama is elected and the Democrats gain a significant number of new congressional seats in November. Whereas presumptive Republican nominee John McCain has endorsed DADT, Sen. Obama has called for its repeal. Nevertheless, Sen. Obama hasn’t made DADT a major talking point in his campaign, probably because he wants to avoid repeating President Bill Clinton’s missteps in 1993 when DADT was enacted into law. (Prior to that time, the military’s ban on service by gay personnel was a matter of Executive Branch policy, not federal law.) Sen. Obama has also expressed support for limited recognition of same-sex couples and the repeal of DOMA, although he opposes marriage equality. Sen. McCain opposes marriage equality and, apparently, civil unions and similar legal recognition for same-sex couples.

For now, the gay citizens of Norway — including those in the military — can look forward to marrying. Meanwhile, in the US, marriage equality exists in only two states, with its status in California threatened by a major ballot initiative. And the Servicemembers’ Legal Defense Network (SLDN) has had to warn active-duty military personnel that marrying someone of the same sex in California or Massachusetts means risking their military careers, noting that the federal statute enacting Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell clearly states “A member of the armed forces shall be separated from the armed forces” if “the member has married or attempted to marry a person known to be of the same biological sex.”

Copyright © 2008 by Gregory M. Herek. All rights reserved.

Permalink ·

June 3, 2008

Posted at 3:36 pm (Pacific Time)

Charles Moskos, the military sociologist who helped to craft the “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” policy, died of cancer on May 31.

Moskos, a professor of sociology at Northwestern University from 1966 until his retirement in 2003, is credited with helping to design AmeriCorps and was an expert on racial integration in the military. His books include The Military: More Than Just a Job?, Black Leadership and Racial Integration the Army Way, and The Postmodern Military. He received numerous honors and awards, including membership in the American Academy of Arts and Sciences and the Distinguished Service Award, the US Army’s highest decoration for a civilian.

In recent years, however, he was best known for his role in helping to design the US military’s current policy on gay personnel.

According to an obituary posted on the Michael D. Palm Center website:

Until the end of his life, Moskos was always willing to engage his colleagues in discussions of ideas, and he held steadfastly to his beliefs even when they were unpopular. According to Palm Center Director Aaron Belkin, “Charlie consistently defended the ‘don’t ask, don’t tell’ policy, but was also concerned about the effect it was having on gay and lesbian troops.” Scholars and activists on all sides of this issue were impressed over the years with Moskos’s ability to defend and critique the policy. In 2000, for instance, he called the effects of the policy “insidious” because gays and lesbians have sometimes been cowed into tolerating harassment because they were fearful that reporting it could bring them unwanted scrutiny.

Belkin added that, “Moskos operated in a tradition of practical sociology that affected people’s lives in tangible ways. His passion, intellect and good nature will be sorely missed.”

Palm Center Senior Research Fellow Nathaniel Frank’s review of Moskos’ role in the DADT debate can be found on their website.

Discussions of the social science data relevant to the DADT policy can be found in my 2006 post, “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” Redux, and in the Beyond Homophobia archives.

Copyright © 2008 by Gregory M. Herek. All rights reserved.

Permalink ·

December 20, 2006

Posted at 11:17 am (Pacific Time)

In an interview with the Washington Post yesterday, President Bush disclosed his plans to increase the US military’s troop strength “to meet the challenges of a long-term global struggle against terrorists.”

In light of this proposal, it’s appropriate to ask (yet again) whether excluding sexual minorities from the US armed forces makes any sense.

The Pentagon has repeatedly predicted that the presence of openly gay and lesbian personnel would reduce the military’s morale and effectiveness and would deter heterosexuals from enlisting. As I’ve detailed in previous postings, empirical support for those claims has always been lacking. Now data from a new survey cast fresh doubts on their validity.

The survey was conducted by Zogby International for the Michael D. Palm Center (formerly the Center for the Study of Sexual Minorities in the Military), located at the University of California, Santa Barbara. It measured the opinions of 545 current and former military personnel, all of whom served in Iraq or Afghanistan or in combat support roles directly related to those operations.

A detailed report of the survey results can be downloaded from the Michael D. Palm Center. Here are four key findings.

1. The “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” policy is not strongly supported by combat personnel and veterans.

Only a minority (37%) supported DADT, saying they disagree “with allowing gays and lesbians to serve openly in the military.” The remainder agreed with allowing openly gay service members (26%), were neutral (32%), or weren’t sure (5%).

2. Many military personnel know or suspect that their unit includes gay or lesbian members.

Nearly one fourth (23%) of the respondents knew for certain that at least one member of their unit was gay or lesbian. A larger proportion (45%) suspected their unit included a gay or lesbian member. Of those who knew for certain, 55% said the presence of homosexual personnel in the unit was well known by others. Most of them (59%) had been told directly by the gay or lesbian individual.

3. Personnel who know their unit includes gay or lesbian members generally don’t perceive damage to morale.

About two thirds of those who knew for certain that their unit included one or more gay members did not believe that the latter’s presence affected either the respondent’s personal morale (66%) or the morale of the unit (64%). Only 28% believed it had a negative effect on their own morale, and 27% perceived a negative effect on their unit’s morale. By contrast, among respondents who neither knew nor suspected that a member of their unit was gay or lesbian, 58% expected that an openly gay or lesbian member would have a negative impact on their unit’s morale.

4. Allowing openly gay and lesbian personnel to serve is unlikely to reduce reenlistment or impair future recruitment.

The vast majority of respondents (78%) said their decision to join the military was based on their sense of duty and a desire to serve their country. A substantial proportion also said their decision was influenced by non-wage benefits, such as retirement or health care (62%), and by the prospect of receiving funds for college tuition (54%). Only 2% acknowledged “knowing that gays are not allowed to serve openly” as a factor in their decision. In a separate question, only 10% of respondents said they would not have joined the military if gay and lesbian personnel were allowed to serve openly.

* * * * *

In recent years, opinion polls of US civilian samples have shown strong support for allowing gay men and lesbians to serve openly in the military. The new Palm Center poll indicates that DADT isn’t strongly supported by combat personnel and doesn’t appear to play a significant role in enlistment decisions. Moreover, fears that the presence of openly gay personnel will damage morale are much greater among those who haven’t actually had any lesbians or gay men in their unit (insofar as they know) than among those who knew their unit included at least one sexual minority member.

In response to the survey, Congressman Marty Meehan (D-MA) said, “It is long past time to strike down ‘Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell’ and create a new policy that allows gays and lesbians to serve openly.”

Let’s hope the new Congress will consider data such as these and follow Mr. Meehan’s lead.

Copyright © 2006 by Gregory M. Herek. All rights reserved.

Permalink ·

November 19, 2006

Posted at 1:49 pm (Pacific Time)

The Pentagon is encountering an inconvenient obstacle in justifying its antigay policies. It’s slowly learning it can no longer get away with equating homosexuality and sickness.

The Department of Defense (DoD) recently came under public scrutiny for its 1996 Instruction on Physical Disability Evaluation. The final appendix of the 88-page memo listed “conditions and defects” that are not considered physical disabilities but nevertheless warrant separation from the armed services. Among these conditions and defects: “Certain Mental Disorders including … Homosexuality.”

In June, the Pentagon was called to task by the US mental health profession’s two major organizations — the American Psychiatric Association and the American Psychological Association. Both APAs challenged the DoD’s factual error of labeling homosexuality a mental disorder and requested that the Instruction be corrected.

The DoD subsequently released a revised Instruction in which homosexuality was moved out of the “Certain Mental Disorders” category. But it’s still listed as a “defect” along with dyslexia, motion sickness, enuresis (bed-wetting), and “repeated veneral disease infections,” among others.

As was widely reported last week, the two APAs once again sent letters to the Pentagon. They acknowledged the DoD’s correction of the mental illness error, but noted that homosexuality isn’t a defect and pointed out that labeling it as such stigmatizes sexual minorities.

What’s particularly noteworthy about this story is the historic realignment it represents in how homosexuality is regarded by the institutions of American society.

The US military didn’t maintain regulations against homosexual activity until 1917, and then the sanctions focused on conduct, not sexual orientation. It wasn’t until the years immediately prior to World War II that the military began to exclude homosexual persons from its ranks, and that policy was based on a medical-psychiatric rationale.

Thus, the mental health profession played a central role in the original policy barring homosexuals from military service.

In 1973, however, the American Psychiatric Association removed homosexuality from its official list of mental illnesses, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, or DSM, which had included homosexuality since 1952. The American Psychological Association quickly endorsed this action and, in the years since, the two professional associations have taken a leading role in working to eradicate the stigma historically associated with homosexuality.

After it lost the support of psychiatry and psychology, the military sought other justifications for barring gay, lesbian, and bisexual personnel. Eventually, it settled on a rationale that emphasized supposed threats to unit cohesion and heterosexuals’ privacy rights. In essence, the Pentagon now argues that heterosexual personnel have so much antipathy toward gay people that they would be unable and unwilling to set aside that hostility for the good of the military mission. Moreover, the DoD portrays itself as powerless to confront this hostility in the manner it deals with, for example, racial discrimination or sexual harassment.

Of course, this argument is based on ideology rather than empirical data. US allies have successfully instituted policies that allow gay personnel to serve in their militaries. And empirical research reveals serious flaws in the Pentagon’s reasoning.

In the past, society’s major institutions spoke with one voice in condemning homosexuality. Organized religion declared it a sin. The law declared it a crime. And medicine — specifically psychiatry and psychology — declared it a sickness. The vocabularies used by these different institutions provided a quiver of rhetorical arrows for denigrating homosexuality and gay people — as immoral, criminal, sick.

The hegemony of heterosexism is crumbling, however. After the Supreme Court’s Lawrence v. Texas ruling, consenting adult homosexual conduct isn’t illegal in the civilan world. And, as every student of introductory psychology learns, homosexuality hasn’t been considered a sickness for more than three decades.

Maybe the recent interventions by the two APAs will help the Pentagon to begin to grasp this fact.

Copyright © 2006 by Gregory M. Herek. All rights reserved.

Permalink ·

« Previous entries Next Page » Next Page »