June 17, 2015

Posted at 2:00 pm (Pacific Time)

Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsberg has been quoted as saying the Court’s 1973 Roe v. Wade decision went “too far, too fast.”

Her comment has sometimes been cited in speculation that the Court won’t rule that people have a constitutional right to marry a same-sex partner because the Justices are reluctant to get too far ahead of public opinion.

However, public opinion may be well ahead of the Court in this arena. As we await a ruling in the Orbergefell marriage equality cases, it’s a good time to reflect on current public sentiment about marriage rights for same-sex couples, and how and why it has shifted over the last two decades.

Public Opinion Today

Last week, the Pew Research Center reported that 57% of the respondents in their latest national survey (most of whom presumably were heterosexual) said they support “allowing gays and lesbians to marry legally.” Only 39% were opposed.

Compare this to a 2001 Pew poll in which the numbers were reversed: 57% opposed marriage equality and only 35% supported it.

A recent Gallup poll showed the same remarkable turnaround: 60% of their respondents now endorse the statement that “marriages between same-sex couples should be recognized by the law as valid, with the same rights as traditional marriage.”

As with the Pew data, earlier Gallup surveys revealed a quite different pattern. In 2005, 59% opposed marriage equality and only 37% supported it. Still earlier, in 1996, marriage rights for same-sex couples were opposed by more than two thirds (68%) of Gallup respondents, with only 27% in support.

Polling data on marriage equality have been somewhat confusing because different surveys have yielded different numbers. As early as 2010, a few already showed a majority of Americans favoring marriage equality. And even today some still show less than half of the public supporting marriage equality.

This variability is largely explained by methodological differences among the polling organizations, according to a meta-analysis by UCLA political scientist Andrew Flores that was recently published in Public Opinion Quarterly.

When Dr. Flores combined the data from more than 130 different polls, controlling statistically for variations in question wording and “house effects” (i.e., differences among polling organizations in how they collect and analyze their data), he found a clear trend: Support for marriage equality has increased fairly steadily since 1996, with a majority of the public endorsing it by 2014.

The trend of shifting attitudes isn’t limited to marriage equality. We see it as well in public opinion about adoption rights, the ability of same-sex couples to be good parents, protection from employment discrimination, and other issues relevant to law and policy. And it is also evidenced by a steady increase in favorable attitudes toward lesbian and gay people in recent years. (Attitudes toward bisexual women and men have probably changed as well, but few polls have included questions designed to specifically tap those attitudes.)

Change has occurred in nearly every demographic group, although it’s more evident in some groups than in others. For example, marriage equality support has increased more among Democrats and Independents than Republicans. But Republicans’ support has nevertheless been increasing as well.

Is the Shift Generational or Individual?

How can we explain these seismic shifts over a relatively brief time span?

They’re often attributed to ongoing population turnover. According to this explanation, individuals aren’t changing their opinions. Rather, change results from older generations dying out and younger ones taking their place. On average, older people are less likely than their younger counterparts to support marriage equality or express favorable attitudes toward sexual minorities. As time passes and younger generations come of age, their attitudes become more dominant in society as a whole.

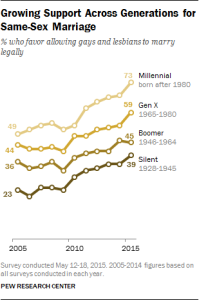

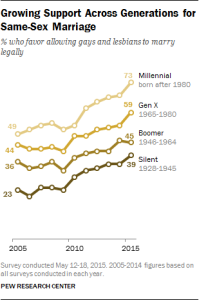

This pattern of generational replacement is evident when polling data are broken down by age groups. As shown in the Pew data, for example, support for marriage equality is lowest among adults born during the Depression Era but increases steadily in each successive generation. Baby Boomers are more supportive than their elders, GenXers are more supportive than Boomers, and Milliennials show the strongest support of any age group.

But generational replacement is only part of the story. The Pew graph shows that opinions have also been shifting within each age group. In other words, attitude change isn’t happening only in the population as a whole; heterosexual individuals have been changing their minds about sexual minorities, and at a rapid pace.

In fact, individual change is the primary force behind the big shifts in public opinion. When researchers Gregory Lewis and Lanae Hatalsky combined data from more than 128,000 respondents in nearly 100 national surveys conducted between 2004 and 2011, they found that only 25% of the shift in overall support for marriage equality during those 8 years could be attributed to generational replacement. Most of the change – 75% of it – resulted from individuals who once opposed or were undecided about marriage equality coming to support it.

Why Are People Changing Their Minds?

Why have so many individual Americans changed their minds? There’s no single answer to this question; people have different reasons. But we can see a common thread running through those reasons if we assume that people generally adopt attitudes and opinions to meet their important psychological needs and to feel good about themselves. When any particular attitude stops serving these purposes, it’s susceptible to change.

For example, heterosexual people whose sense of self is grounded mainly in their personal value system – whether deriving from religion, politics, ethics, or other sources – are likely to express attitudes that serve to affirm those values. Whether they support or oppose marriage equality, their attitude functions to solidify their sense of personal identity and increase their feelings of self-worth. If they come to see their stance on marriage equality as inconsistent with key aspects of their value system, however, they may be open to change.

A 2013 Pew survey, for example, found that 28% of those who endorsed marriage equality said they hadn’t always held that view. When asked what made them change their minds, roughly one third cited values — e.g., their own moral and religious beliefs or their support for equality. For them, being true to those values came to mean expressing support for marriage equality.

Other heterosexual people have especially strong needs for social acceptance and affiliation. The main motivation underlying their marriage equality opinions is their desire to secure approval and support from friends, family, and other important groups. If group norms change, however, clinging to the old attitude may block them from meeting those affiliation needs. As support for marriage equality increasingly becomes the norm throughout much of the United States, people seeking their group’s approval are more and more likely to get it by changing their attitudes to conform with the trend.

About one sixth of respondents in the 2013 Pew survey attributed their new-found endorsement of marriage equality to their perception that social acceptance of it is inevitable. For at least some of them, changing their attitudes may have allowed them to continue to enjoy group acceptance in a changing world.

Attitudes can also function to help people make sense of their own past experiences, including their interactions with people from groups other than their own. Having an unpleasant encounter with a lesbian, gay, or bisexual person may lead heterosexuals to hold negative feelings toward all sexual minorities. Conversely, good experiences can generalize to a positive attitude toward the entire group and issues that affect it.

Interestingly, it turns out that heterosexuals’ personal contact with lesbian, gay, or bisexual people usually results in more positive attitudes, not only toward the specific person involved, but also toward sexual minorities as a group. Having a friend or relative who is gay, lesbian, or bisexual can be a potent motivator for heterosexuals to change their opinions.

We see evidence of this pattern in the 2013 Pew poll. About one third of the participants who had come to support marriage equality cited their personal experiences with gay or lesbian friends, family members, or acquaintances as the reason why.

As I’ve discussed in previous blog posts, personal contact appears to be especially influential when it includes open discussion of what it’s like to be lesbian, gay, or bisexual. Such discussions can lead heterosexuals to think about sexual minorities in a new way and to rethink the connections between their personal values and their attitudes toward sexual minorities. And when heterosexuals see that their own family or friendship circle includes sexual minorities, the desire to maintain their social ties can motivate them to rethink their attitudes.

The functional approach I’ve used to organize this discussion focuses on individual psychology. But shifts in public opinion about marriage equality aren’t simply a matter of what goes on inside people’s heads. The larger culture’s beliefs and norms make possible the relationship between particular attitudes and specific psychological needs. As cultural institutions have changed in recent years, so have the ways in which heterosexuals’ attitudes toward marriage equality and sexual minorities are linked to their values, worldview, group memberships, and personal relationships. (For a more sociological perspective on attitude change, see this post from The Conversation.com.)

Back to Justice Ginsburg

Perhaps another quotation from Justice Ginsburg is more fitting to the current moment than her “too far, too fast” comment.

Earlier this week, she displayed a clear understanding of how and why public attitudes toward lesbian, gay, and bisexual people have changed when she cited the power of personal contact and coming out in advancing sexual minority rights:

“People looked around … and it was my next-door neighbor, of whom I was very fond, my child’s best friend, even my child…. They are people we know and we love and we respect, and they are part of us…. Discrimination began to break down very rapidly once they no longer hid in a corner or in a closet.”

If, as many observers expect, she and a majority of her colleagues on the Court affirm same-sex couples’ right to marry, they won’t be getting ahead of public opinion. Rather, they’ll be following the lead of the American people.

Copyright © 2015 by Gregory M. Herek. All rights reserved.

Permalink ·

September 16, 2014

Posted at 1:00 am (Pacific Time)

Last week, the 7th Circuit Court of Appeals upheld lower court rulings striking down anti-marriage laws in Indiana and Wisconsin. Even those of us who aren’t legal scholars can find good reading in Judge Richard Posner’s written opinion, which skewered the states’ arguments against marriage equality.

As a social scientist, I was pleased that his legal analysis was informed by data from social and behavioral research. And I was gratified that he referenced some of my own work.

Early in his 40-page decision, Judge Posner wrote,

“We begin our detailed analysis of whether prohibiting same-sex marriage denies equal protection of the laws by noting that Indiana and Wisconsin … are discriminating against homosexuals by denying them a right that these states grant to heterosexuals, namely the right to marry an unmarried adult of their choice. And there is little doubt that sexual orientation, the ground of the discrimination, is an immutable (and probably an innate, in the sense of in-born) characteristic rather than a choice. Wisely, neither Indiana nor Wisconsin argues otherwise.” (p. 9, my emphasis)

The evidence he cited in support of this assertion included materials from the American Psychological Association and a paper on which I was the lead author, describing findings from a survey I conducted with a nationally representative sample of lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults.

This blog post is about the research and the context in which I conducted it.

*Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â *Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â *Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â *Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â *

Early research on sexual minority subcultures in the United States tended to focus on gay men. And the researchers often reported that most gay men felt they hadn’t chosen their sexual orientation. For example, in his 1951 book, The Homosexual in America: A Subjective Approach, sociologist Edward Sagarin (writing under the pseudonym Donald Webster Cory) wrote:

“This does not mean that sexual inversion [homosexuality] is voluntary, and that one need only exercise good judgment and will-power in order to overcome it or to choose some other pathway. Not at all. It is entirely involuntary and beyond control, because one did not choose to want to be homosexual.” (p. 183)

And psychologist Evelyn Hooker, in her 1965 paper, Male Homosexuals and Their “Worlds” (in Judd Marmor’s edited book, Sexual Inversion: The Multiple Roots of Homosexuality), reported from her ethnographic observations of gay male communities:

“One of the important features of homosexual subcultures is the pattern of beliefs or the justification system. Central to it is the explanation of why they are homosexuals, involving the question of choice. The majority believe either that they were born as homosexuals or that familial factors operating very early in their lives determined the outcome. In any case, homosexuality is believed to be a fate over which they have no control and in which they have no choice.” (p. 102)

In recent years, religious conservatives have strongly disputed this view, and the argument that homosexuality is a sinful choice has achieved considerable prominence in their public rhetoric. In the 1990s, they mounted media campaigns promoting the notion that people can and should stop being gay. The director of one of these ex-gay campaigns told the New York Times that its goal was to strike at the assumption that homosexuality was immutable and that gay people therefore need protection under anti-discrimination laws.

Not surprisingly, public opinion reflects this dimension of the culture wars. Heterosexuals’ attitudes toward lesbians and gay men are reliably correlated with their beliefs about choice. Antigay heterosexuals are likely to assert that homosexuality is a choice, whereas unprejudiced heterosexuals are likely to believe that sexual orientation is inborn or otherwise not chosen. (As discussed below, the question of whether heterosexuals choose their orientation is rarely asked.)

*Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â *Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â *Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â *Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â *

In the 1990s, I was surprised to discover that, despite all the debate and heated rhetoric, relatively little empirical research had directly examined how people perceive their own sexual orientation.

Indirect evidence for a lack of choice was available. For example, most participants in the Kinsey studies of the 1940s and 1950s reported they had experienced sexual attraction only to one sex (men or women) throughout their entire lives; but the Kinsey team did not ask directly about perceptions of choice.

Illuminating research was conducted by sociologist Vera Whisman, who set out to study lesbians and gay men who said they had chosen their sexual orientation. However, as she reported in her book, Queer By Choice, most of her sample did not experience their patterns of sexual attractions as a choice. Those who were “queer by choice” were typically referring to choosing their sexual behaviors and the labels and identities they adopted for themselves.

Otherwise, anecdotal and autobiographical accounts were available and a few studies reported relevant questionnaire data from small samples. But as best I could tell, no large-scale studies had asked people whether they perceived their own sexual orientation (whether hetero-, homo-, or bisexual) as a choice.

*Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â *Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â *Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â *Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â *

This lack of data prompted me to begin asking about choice in my own research.

Based on the available evidence, I expected to find that many – probably most – gay men didn’t perceive their sexual orientation to be a choice.

For women, however, I thought the pattern might be different. Many feminists argued that lesbianism is a choice women can (and should) make for themselves. And in some early studies, gay men tended to report having been aware of their homosexuality at an earlier age than lesbians, which might be evidence of a gender difference in the experience of choice.

These and other patterns led me to tentatively hypothesize that lesbians would be more likely than gay men to report they experienced some degree of choice about their sexual orientation.

In an exploratory study during the 1990s with a relatively small community sample that included 125 gay and lesbian adults, these hypotheses were supported. My colleagues and I found that most of the gay men (80%) said they had no choice at all about their sexual orientation. The proportion of lesbians who said they had no choice was smaller, but still a majority (62%).

While these findings were interesting, the sample was small. I subsequently decided to ask a similar question in two survey studies with larger and more representative samples that also included enough bisexual women and men to permit meaningful analyses of their responses.

In the first of those surveys, we collected questionnaire data from 2,259 gay, lesbian, and bisexual adults in the greater Sacramento area. One questionnaire item was, “How much choice do you feel that you had about being lesbian/bisexual?” [for men the wording was “gay]/bisexual”]. The 5 response options were “no choice at all,” “very little choice,” “some choice,” “a fair amount of choice,” and “a great deal of choice.”

The results weren’t dramatically different from those we obtained in the pilot study: 87% of the gay men reported they experienced “no choice at all” or “very little choice” about their sexual orientation. Once again, women perceived having more choice than men. Even so, most lesbians (nearly 70%) reported having little or no choice.

It is perhaps not surprising that bisexuals reported feeling they had more choice about their sexual orientation. Nevertheless, nearly 59% of bisexual men and 45% of bisexual women said they experienced little or no choice. Another 15% and 20%, respectively, said they had only “some choice.”

This study’s sample was large but it wasn’t a probability sample, i.e., one that is representative of the population at large. We had recruited the participants mainly through Northern California lesbian, gay, and bisexual community organizations and at community events, most of them in the Sacramento area. People who weren’t active in the community or weren’t open about their sexual orientation were probably underrepresented.

I subsequently had the opportunity to assess how well these findings fit the population as a whole when I surveyed a nationally representative sample of self-identified lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults. We asked them “How much choice do you feel you had about being lesbian?” [Or gay or queer or bisexual or homosexual, depending on the term they had previously said they preferred for describing themselves.] Four response options were available: “no choice at all,” “a small amount of choice,” “a fair amount of choice,” and “a great deal of choice.”

The responses of gay men and lesbians were strikingly similar to those we obtained from the Sacramento-area community sample: 88% of the gay men reported “no choice at all” about being gay, with another 6.9% saying they experienced “a small amount of choice.” Only 5% reported they experienced “a fair amount” or “a great deal” of choice. Among lesbians, 68.4% reported no choice, and another 15.2% reported experiencing a small amount of choice; only 16% experienced a fair amount or a great deal of choice.

Thus, 95% of gay men and 84% of lesbians reported experiencing little or no choice about their sexual orientation. This is the finding Judge Posner cited last week in his opinion.

In contrast to the community study, a majority of bisexuals in the national sample reported having little or no choice about their sexual orientation, although they were less likely than gay men and lesbians to say they experienced no choice at all. Among bisexual men, 38.3% said they experienced no choice, and another 22.4% experienced a small amount of choice, a total of 60.7%. Among bisexual women, the numbers were 40.6% and 15.2%, respectively, a total of 55.8%.

None of these surveys explicitly defined the term choice, so we don’t know whether respondents interpreted it as referring to their pattern of attractions, their sexual behaviors, their identity, or some other facet of sexual orientation. Based on Vera Whisman’s research, cited above, it seems likely that most were referring to the amount of choice they experience in their sexual attractions and desires.

*Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â *Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â *Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â *Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â *

What about heterosexuals? Do they perceive their sexual orientation as a choice?

To the best of my knowledge, no published research based on a probability sample of heterosexual adults reports data that directly answer this question. I intended to ask it in a national survey I conducted in the 1990s, but was dissuaded from doing so by other members of my research team. They convinced me the question would create problems during data collection because most heterosexuals simply wouldn’t know how to answer it.

This asymmetry in who can answer the choice question can be understood as a reflection of sexual stigma. One manifestation of stigma is the widespread assumption that heterosexuality is normal and unproblematic. Few heterosexuals are ever asked what made them straight, and most have probably never thought about the origin of their own attractions to the other sex.

Homosexuality, by contrast, is viewed as problematic. Nonheterosexuals are routinely asked what made them “that way” and, in the course of coming out, they often ask themselves this question. Even when a scientific study evenhandedly examines the origins of all sexual orientations, its subject matter is typically characterized as what causes people to be gay or bisexual.

In this context of stigma, it is perhaps not surprising that I encountered some raised eyebrows when I initially shared my findings about perceptions of choice with other researchers – not so much because of the numbers, but simply because I had asked the question.

Some assumed that documenting how people perceive their sexual orientation would be the basis for arguing that gay, lesbian, and bisexual people shouldn’t be persecuted because “it’s not their fault” – they never chose to be “that way.” This argument is perceived (often correctly) as implicitly suggesting that (a) being lesbian, gay, or bisexual is a defect, and (b) if people did choose to be anything other than heterosexual, they would deserve to be discriminated against.

*Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â *Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â *Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â *Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â *

But although Judge Posner’s opinion takes up the question of choice – as did Judge Vaughn Walker, who cited the same research in his decision overturning California’s Proposition 8 – he doesn’t treat homosexuality as a defect. Nor does he suggest that gay, lesbian, and bisexual people would deserve to be persecuted if they freely chose their sexual orientation.

However, Judge Posner recognizes that lesbian, gay, and bisexual people constitute an identifiable minority group defined by an immutable characteristic that is irrelevant to a person’s ability to contribute to society. Consequently, any attempt by the state to discriminate against them must serve some important government objective.

And, as he concluded, the rationale offered by Wisconsin and Indiana for their laws denying marriage rights to same-sex couples, “is so full of holes that it cannot be taken seriously…. The discrimination against same-sex couples is irrational, and therefore unconstitutional…” (pp. 7-8).

*         *         *         *         *

Here are the bibliographic sources for my studies, described above.

Herek, G. M., Cogan, J. C., Gillis, J. R., & Glunt, E. K. (1998). Correlates of internalized homophobia in a community sample of lesbians and gay men. Journal of the Gay and Lesbian Medical Association, 2(1), 17-25.

Herek, G. M., Gillis, J. R., & Cogan, J. C. (2009). Internalized stigma among sexual minority adults: Insights from a social psychological perspective. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 56, 32-43.

Herek, G. M., Norton, A. T., Allen, T. J., & Sims, C. L. (2010). Demographic, psychological, and social characteristics of self-identified lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults in a U.S. probability sample. Sexuality Research and Social Policy, 7, 176-200.

A brief introduction to sampling terminology and methods is available on my website.

Copyright © 2014 by Gregory M. Herek. All rights reserved.

Permalink ·

June 12, 2009

Posted at 12:22 pm (Pacific Time)

Larry Kurdek, one of the world’s leading social science researchers on lesbian and gay committed relationships, died yesterday in Ohio.

Over the past 25 years, Larry published dozens of important empirical and theoretical articles and chapters about gay and lesbian couples. Among other findings, his research demonstrated that the factors predicting relationship satisfaction, commitment, and stability are remarkably similar for both same-sex cohabiting couples and heterosexual married couples. His work was featured prominently in amicus briefs that the American Psychological Association (APA) filed in court cases challenging marriage laws in New Jersey, Connecticut, California, Iowa, and elsewhere. He received the 2003 Award for Distinguished Scientific Contributions from the Society for the Psychological Study of Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Issues (APA Division 44).

Larry helped to craft the APA’s Resolution on Sexual Orientation and Marriage, in which the Association committed itself to “take a leadership role in opposing all discrimination in legal benefits, rights, and privileges against same-sex couples.” He also helped to develop the APA’s Resolution on Sexual Orientation, Parents, and Children, in which the Association went on record opposing “any discrimination based on sexual orientation in matters of adoption, child custody and visitation, foster care, and reproductive health services.”

Larry was a great lover of dogs. After receiving his cancer diagnosis, he decided to pursue research on the emotional bonds between people and their dogs. In 2008, he published a paper titled “Pet dogs as attachment figures” in the Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. In it, he documented similarities between the attachments people form with their dogs and those they form with other humans.

According to Gene Siesky, Larry’s partner, he passed away peacefully at home with his dogs by his side, just as he had wanted.

I first met Larry back in the 1980s. I got to see him only infrequently over the years, but we had an ongoing e-mail correspondence. He gave me lots of information and guidance about my own work and writing on marriage and relationships. During the time that I chaired the Scientific Review Committee for the Wayne F. Placek Awards, he was always willing to provide thoughtful reviews of proposals. And we sent each other condolences when we lost beloved dogs.

I’ll miss Larry as both a colleague and a friend. His premature passing is a great loss to the field of psychology and to everyone who supports marriage equality.

*Â Â Â Â *Â Â Â Â *Â Â Â Â *Â Â Â Â *

John Flach, Chair of the Psychology Department at Wright State University, shared these thoughts about Larry in an e-mail:

Larry had been battling cancer for several years. Up until a few weeks ago he was still working and working out. Those of you who know Larry, know that he was very dedicated to his work and his personal fitness.

Larry will be greatly missed by his colleagues in the Psych department. In many respects, Larry was the spiritual center of our department – helping us to always focus on quality.

Larry completed the Ph.D. at University of Illinois, Chicago in 1976 and began as an assistant professor at WSU that same year. He was promoted to Professor in 1984. He was an excellent teacher – teaching courses in statistics and developmental psychology. He was a leading researcher on commitment and satisfaction in family relationships with over 145 journal publications. And he was dedicated to serving the department, college, and university. For example, he was instrumental in developing the department bylaws.

I relied heavily on Larry’s support and guidance and will personally miss him very much.

*Â Â Â Â *Â Â Â Â *Â Â Â Â *Â Â Â Â *

A viewing and memorial service will be held this weekend at Newcomer Funeral Home, Beavercreek, Ohio. In lieu of flowers, contributions can be made to the Larry Kurdek Memorial Scholarship Fund in care of the Psychology Department at Wright State University, Dayton, Ohio.

Copyright © 2009 by Gregory M. Herek. All rights reserved.

Permalink ·

May 31, 2009

Posted at 12:38 pm (Pacific Time)

Now that the California Supreme Court has upheld Proposition 8’s constitutionality, some marriage equality supporters are ready to begin collecting signatures for a new ballot measure to overturn it in next year’s election.

Instead, I hope Californians who support marriage rights for same-sex couples will take a deep collective breath and engage in level-headed strategizing about how best to achieve the long-range goal of marriage equality.

There are at least two good reasons not to put an anti-Prop. 8 measure on the 2010 ballot.

First, such an initiative stands a strong chance of losing. Highly respected statewide polls, such as those conducted by Field and the Public Policy Institute of California (PPIC), indicate that support for marriage rights for California same-sex couples hasn’t increased noticeably since November. In a February Field Poll, for example, fewer than half of registered voters said they would support a new ballot measure to legalize same-sex marriage, and about the same percentage would oppose it. Only a 49% plurality said they generally support “California allowing homosexuals to marry members of their own sex and have regular marriage laws apply to them.” And a March PPIC survey found that the state’s likely voters oppose marriage equality by a 49-45% margin.

These numbers don’t bode well for a 2010 ballot campaign to overturn Prop. 8. Just over a year ago, the Field Poll found that more than half of likely voters opposed changing the state constitution to define marriage as between a man and a woman. PPIC surveys similarly revealed a widespread reluctance to enact Prop. 8. Yet that solid majority evaporated during the final months of last fall’s campaign. Launching a new initiative with support from less than half of the electorate is ill advised. And if the next campaign fails, it’s highly unlikely that the necessary resources will be available anytime soon to mount yet another ballot fight.

Second, win or lose, another initiative campaign will exact a substantial psychological toll. Research shows that marriage amendment campaigns have negative mental health effects on the people whose lives they target. A recently published nationwide study, for example, found that during the months leading up to the 2006 November election, psychological distress increased among lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults living in states where an antigay marriage measure was on the ballot, but not among their counterparts living elsewhere. By Election Day, sexual minority residents of the states with antigay ballot measures had, on average, significantly higher levels of stress and more symptoms of depression than their neighbors in other states.

Comparable research on the 2008 election isn’t yet available but the limited data I’ve seen, supplemented by my own observations, lead me to believe that the Proposition 8 campaign had a similar, negative effect on many Californians. Perhaps the psychological fallout of another statewide campaign will be tolerable if Prop. 8 is repealed. But without a strong likelihood of succeeding, it is irresponsible to subject lesbian, gay, and bisexual Californians to another prolonged period of daily attacks on the legitimacy of their relationships and families.

It has become almost a cliche to assert that time is on the side of the marriage equality movement. Younger voters support marriage rights for same-sex couples more strongly than their elders (although the strength of support among young voters shouldn’t be overstated). That view will eventually achieve majority status in California, perhaps even by 2012. But almost certainly not by next year.

I’m not suggesting that marriage equality supporters should sit on their hands. There’s much work to be done to create a solid majority of California voters who feel they have a personal stake in overturning Prop. 8.

For example, heterosexuals who support marriage rights for same-sex couples can become agents of change by making their opinions known to their spouse, family, neighbors, and coworkers.

And it’s critically important for lesbian, gay, and bisexual Californians to speak directly with their straight relatives and friends about their own experiences, to explain how measures like Prop. 8 personally affect them. In the wake of the November election, the American Civil Liberties Union and other groups launched the Tell 3 Campaign to encourage and assist sexual minority adults in telling their stories to the people who love and respect them. Having such conversations is one of the most potent strategies for changing attitudes. Yet, according to my own research, they occur all too infrequently.

Last week’s Supreme Court decision has rightly evoked strong feelings among gay, lesbian, and bisexual Californians and their heterosexual supporters. That emotion can be harnessed to build a successful movement for marriage equality in California. But it shouldn’t push us prematurely into a ballot campaign that poses a significant risk not only of losing, but also of ultimately harming many lesbian, gay, and bisexual Californians.

* * * * *

A briefer version of this essay appeared in the Sacramento Bee on Sunday, May 31, 2009.

Copyright © 2009 by Gregory M. Herek. All rights reserved.

Permalink ·

May 24, 2008

Posted at 2:40 pm (Pacific Time)

A new Los Angeles Times/KTLA poll reveals some of the challenges facing supporters of marriage equality in California during the next 5 months. But it also suggests that passage of a state constitutional amendment to restrict marriage to heterosexual couples is hardly a certainty.

The Bad News

At first glance, the poll results are likely to be disheartening to marriage equality supporters. A majority of participants said they disapprove of last week’s California Supreme Court decision that denying marriage rights to same-sex couples is unconstitutional. Here’s the relevant question:

“As you may know, last week the California Supreme Court ruled that the California Constitution requires that same-sex couples be given the same right to marry that opposite-sex couples have. Based on what you know, do you approve or disapprove of the Court’s decision to allow same-sex marriage in California?”

- 41% Approve

- 52% Disapprove

- 7% Don’t know

The depth of public opposition to the Court’s ruling is indicated by the fact that 42% of those polled strongly disapproved of it, compared to only 29% who strongly approved.

These opinions generally translated into support for the proposed ballot initiative:

“As you may also know, a proposed amendment to the state’s constitution may appear on the November ballot which would reverse the Supreme Court’s decision and reinstate a ban on same-sex marriage. The amendment would state that marriage is only between a man and a woman. If the November election were held today, would you vote for or against the amendment to make marriage only between a man and a woman?”

- 54% of registered voters would vote FOR it

- 35% of registered voters would vote AGAINST it

- 9% don’t know

A question about general attitudes toward legal recognition of relationships between two people of the same sex revealed that nearly two-thirds of California adults believe the state should recognize same-sex couples through marriage or civil unions:

- 35% said “Same-sex couples should be allowed to legally marry.”

- 30% said “Same-sex couples should be allowed to legally form civil unions, but not marry.”

- 29% said “Same -sex couples should not be allowed to either marry or form civil unions.”

- 6% were undecided.

These numbers indicate a small increase in support for marriage equality since April of 2004, when 31% of Californians said same-sex couples should be able to marry. They also indicate a similar rise in the proportion of Californians opposing any recognition of same-sex relationships, from 25% in 2004 to 29% now. The proportion endorsing civil unions but not marriage (effectively, the situation before last week’s Court ruling) decreased from 40% in 2004 to 30% now.

Respondents’ opinions about same-sex relationships didn’t perfectly predict their stated voting intentions. The LA Times‘ extended report on the poll includes the following breakdown of poll respondents:

- 27% support marriage equality and plan to vote against the November initiative.

- 21% oppose any legal recognition and plan to vote for the initiative.

- 21% support civil unions but not marriage and plan to vote for the initiative.

These patterns are somewhat predictable. In addition, however:

- 10% oppose marriage equality but plan to vote against the initiative.

- 7% support marriage equality but plan to vote for the initiative.

Another 14% of respondents gave other combinations of answers to the two questions. Thus, a person’s stated attitudes toward marriage equality don’t necessarily reveal her or his voting intentions. In addition, some voters may be confused about the meaning of voting for the initiative versus opposing it.

Cause for Hope

At first glance, the polling numbers are likely to be disheartening to supporters of marriage equality. Some additional findings, however, offer hope for the fall election and suggest potential strategies for combating the ballot initiative.

First, whether or not the initiative passes will depend on who votes in the fall election. The Times‘ extended report on the poll noted that partisan affiliation and political ideology are key predictors of opinion about the initiative. And, compared to the voters who enacted the anti-marriage Proposition 22 in the March 2000 primary, historical turnout patterns suggest that those who vote this November will be more likely to be Democratic and liberal. When the LA Times analysts constructed a statistical model that factored in the likely characteristics of November voters, they found that “the amendment would still be ahead, but by half the margin found in the survey today.”

Second, although many California voters are currently opposed to marriage equality per se, their views of same-sex relationships are fairly positive. Consider the following results:

- 59% agreed with the statement “As long as two people are in love and are committed to each other it doesn’t matter if they are a same-sex couple or a heterosexual couple.”

- 54% disagreed with the statement, “If gays are allowed to marry, the institution of marriage will be degraded,” while 41% agreed. At the extremes, 38% strongly disagreed and 31% strongly agreed.

- Overall, only 39% said they “personally believe that same-sex relationships between consenting adults are morally wrong,” compared to 54% who said such relationships are “not a moral issue.”

Third, the poll reflects voters’ intentions “if the November election were held today.” More than 5 months remain until the actual vote, however, and the fact that only a small majority supports the initiative at this point may be a sign that its passage is in doubt. The LA Times article noted that “ballot measures on controversial topics often lose support during the course of a campaign” and, for this reason, “strategists typically want to start out well above the 50% support level.” According to Susan Pinkus, the Times Poll Director, “Although the amendment to reinstate the ban on same-sex marriage is winning by a small majority, this may not bode well for the measure.”

Thus, California voters don’t overwhelmingly favor the initiative and, based on historical patterns, their support is likely to erode in the months ahead. Nor do most of them hold exceedingly hostile attitudes toward same-sex relationships. Moreover, those who will turn out to vote in November may be more supportive of marriage equality than the California population as a whole.

Strategies for Winning in November

Nevertheless, supporters of marriage rights in California clearly have a big job ahead of them. In that regard, the poll also highlights some key correlates of attitudes toward the ballot initiative, and thereby suggests approaches to confronting this challenge. In upcoming postings, I’ll discuss several such strategies. For now, I’ll focus on one.

For sexual minority Californians who want to rally opposition to the ballot measure, the poll highlights the importance of reaching out to heterosexual relatives, friends, and colleagues. Among survey respondents who said they don’t have a friend, family member or co-worker whom they know to be gay or lesbian, the ballot initiative was supported by a huge margin — 63% to 25%. But among those who said they know a gay or lesbian person, the initiative was supported by only a plurality — 47% to 41%.

Based on other empirical research about the effects of personal contact on heterosexuals’ attitudes toward sexual minorities, my guess is that these differences would have been even more pronounced if the poll had distinguished between participants who have a close relationship with a sexual minority individual and those who simply are acquainted with someone who isn’t heterosexual.

Interestingly, the benefits of having personal relationships were most pronounced among Democrats and independents. Support for marriage equality was 7 points higher among Democrats who know someone who is gay or lesbian than among Democrats who don’t. Among independents, the difference was 6 points.

Similarly, support for marriage equality was 9 points higher among liberals who know someone who is gay or lesbian, and 5 points higher among moderates. Among Republicans and conservatives, however, knowing a gay person added only a few percentage points.

This pattern could mean that political ideology and partisanship trump personal relationships in shaping attitudes toward marriage equality. Or it could mean that conservatives and Republicans have different kinds of relationships with sexual minorities than do moderates, liberals, Democrats, and independents. My own research, for example, indicates that personal relationships are more likely to reduce heterosexuals’ prejudices when they include open discussion of what it’s like to be gay or lesbian. Maybe conservative Republicans are less likely than others to have those conversations with their sexual minority acquaintances.

At any rate, this pattern — considered in conjunction with other research on sexual prejudice — suggests some actions that sexual minority Californians can start taking today:

- Come out to your relatives and friends. Talk with them about what it’s like to be gay, lesbian, or bisexual.

- If you’re in a committed relationship, introduce your partner to your heterosexual friends and family.

- Talk with them about the initiative. Explain how it will adversely affect you and other people they care about.

- Enlist them as allies; encourage them to persuade their friends to vote against the initiative.

- If you’re planning a wedding, help your heterosexual guests to understand that your marriage may be rendered invalid if the initiative passes.

During the coming months, millions of dollars will be spent on advertising and mass media by both sides in the marriage debate. Those expensive campaigns, however, won’t have nearly as much impact on the vote as will California’s millions of gay, lesbian, and bisexual residents personally reaching out to their heterosexual friends and family members, and urging them to embrace marriage equality.

* * * * *

The Los Angeles Times/KTLA Poll contacted 834 adults (including 705 registered voters) in the state of California by telephone May 20 –21, 2008. An extended report on the poll results is available from the Times website.

Copyright © 2008 by Gregory M. Herek. All rights reserved.

Permalink ·

May 15, 2008

Posted at 4:48 pm (Pacific Time)

Leading up to today’s historic decision striking down state laws that prohibit same-sex couples from marrying, the California Supreme Court received 45 amicus curiae (friend of the court) briefs. The briefs were filed by diverse sources, including California cities, elected officials, law professors, and religious, business, and professional organizations.

It’s often difficult to know what impact such briefs have on judicial decision making. As a contributor to briefs filed by the American Psychological Association (APA) in other cases, I’ve sometimes wondered whether they were even read by the Court.

In today’s written opinion, however, the California Court majority characterized the briefs they’d received as “extensively researched and well-written” and acknowledged having “benefited from the considerable assistance provided by these amicus curiae briefs in analyzing the significant issues presented by this case” (Note 10, pp. 22-23).

While many of the briefs may have influenced the justices’ thinking in a variety of ways, three of them were specifically referenced by the Court.

Two of those briefs were filed by opponents of marriage equality.

- The Court responded to a passage in the brief filed by Pat Robertson’s American Center for Law & Justice, which cited the philosopher John Rawls to argue that recognizing a constitutional right to marry for same-sex couples will devalue the institution and will have detrimental effects on children. The Court responded that, elsewhere in the same work, Rawls explicitly argued that if gay and lesbian “rights and duties are consistent with orderly family life and the education of children, they are, ceteris paribus [all other things being equal], fully admissible” (Note 51, pp. 78-79).

The third amicus brief explicitly cited by the Court was filed by the American Psychological Association, American Psychiatric Association, National Association of Social Workers, and some of their California state affiliates. (In the interests of full disclosure, it’s appropriate to acknowledge that I played a role in writing this brief.)

The APA brief was quoted in reference to the Court’s decision that, while California marriage laws don’t constitute discrimination on the basis of gender or sex, they do unlawfully discriminate on the basis of sexual orientation:

In our view, the statutory provisions restricting marriage to a man and a woman cannot be understood as having merely a disparate impact on gay persons, but instead properly must be viewed as directly classifying and prescribing distinct treatment on the basis of sexual orientation. By limiting marriage to opposite-sex couples, the marriage statutes, realistically viewed, operate clearly and directly to impose different treatment on gay individuals because of their sexual orientation. By definition, gay individuals are persons who are sexually attracted to persons of the same sex and thus, if inclined to enter into a marriage relationship, would choose to marry a person of their own sex or gender.[59] A statute that limits marriage to a union of persons of opposite sexes, thereby placing marriage outside the reach of couples of the same sex, unquestionably imposes different treatment on the basis of sexual orientation (pp. 94-95).

Here’s Footnote 59:

[59] As explained in the amicus curiae brief filed by a number of leading mental health organizations, including the American Psychological Association and the American Psychiatric Association:

“Sexual orientation is commonly discussed as a characteristic of the individual, like biological sex, gender identity, or age. This perspective is incomplete because sexual orientation is always defined in relational terms and necessarily involves relationships with other individuals. Sexual acts and romantic attractions are categorized as homosexual or heterosexual according to the biological sex of the individuals involved in them, relative to each other. Indeed, it is by acting — or desiring to act — with another person that individuals express their heterosexuality, homosexuality, or bisexuality. . . .

Thus, sexual orientation is integrally linked to the intimate personal relationships that human beings form with others to meet their deeply felt needs for love, attachment, and intimacy. In addition to sexual behavior, these bonds encompass nonsexual physical affection between partners, shared goals and values, mutual support, and ongoing commitment.

Consequently, sexual orientation is not merely a personal characteristic that can be defined in isolation. Rather, one’s sexual orientation defines the universe of persons with whom one is likely to find the satisfying and fulfilling relationships that, for many individuals, comprise an essential component of personal identity.”

We made this point to explain that sexual orientation is inherently about relationships. As we documented in the brief (and as I’ve discussed in earlier posts), empirical research indicates that same-sex committed relationships don’t differ from heterosexual committed relationships in their essential psychosocial qualities, their capacity for long-term commitment, and the context they provide for rearing healthy and well-adjusted children.

Thus, the basis for according same-sex couples a legal status different from that of heterosexual couples ultimately boils down to the partners’ sexual orientation and the State’s role in stigmatizing sexual minorities.

The California justices agreed and forcefully rejected sexual orientation discrimination as unconstitutional, not only in the realm of marriage but in all areas. In fact, the Court ruled that instances of sexual orientation discrimination should be subjected to strict judicial scrutiny — the same standard that is applied in cases of racial and gender discrimination.

Of course, the story doesn’t end here. Court rulings typically don’t go into effect until 30 days after they’re issued. And opponents of marriage equality plan to ask the Court to place its decision on hold until the November election, when they hope to qualify a ballot proposition that would amend the state constitution to bar same-sex couples from legally marrying.

Today, however, many Californians — gay, lesbian, bisexual, and heterosexual — are celebrating a tremendous, long sought victory. And, no doubt, many are thinking of themselves as friends of this Court.

Copyright © 2008 by Gregory M. Herek. All rights reserved.

Permalink ·

December 27, 2006

Posted at 10:33 am (Pacific Time)

An early episode of the old TV sitcom, The Many Loves of Dobie Gillis, was titled “Love Is A Science.” In it, Zelda Gilroy introduced Dobie to the concept of propinquity as a source of romantic attraction.

Propinquity refers to physical proximity. Because of their last names, Dobie and Zelda regularly experienced it, thanks to Central High School’s alphabetically arranged student seating charts.

As it happens, social scientists who study relationships have indeed found that propinquity is often a precursor to attraction. In fact, researchers have learned quite a bit about romantic relationships during the decades since Dobie and Zelda’s first on-camera meeting in 1959.

For years, that research focused on heterosexual couples. In the late 1970s, however, Dr. Anne Peplau, a respected social psychologist and relationship researcher, began to study the intimate relationships of same-sex couples with the goal of broadening scientific understanding of all close relationships.

Three decades later, Prof. Peplau is still a leading scholar in relationship science. With new challenges to state marriage laws now proceeding through the Maryland, Connecticut, and Iowa courts, the recent publication of her newest review of the scientific literature on same-sex couples is especially timely.

The article, by Dr. Peplau and her UCLA graduate student, Adam Fingerhut, appears in the 2007 volume of the Annual Review of Psychology, a widely-cited source of authoritative and analytic reviews of current research on a variety of topics.

Titled “TheClose Relationships of Lesbians and Gay Men,” the article summarizes the current state of scientific knowledge about same-sex relationships. It also highlights recent research trends and discusses how the growing body of research on same-sex couples has contributed to scientific understanding of close relationships in general.

Here are some of the main research findings discussed by Peplau and Fingerhut:

- Lesbians, gay men, and heterosexuals seek similar qualities in their romantic partners. “Regardless of sexual orientation, most individuals value affection, dependability, shared interests, and similarity of religious beliefs. Men, regardless of sexual orientation, are more likely to emphasize a partner’s physical attractiveness; women, regardless of sexual orientation, give greater emphasis to personality characteristics.”

- Traditional heterosexual marriages are organized around a gender-based division of labor and a norm of greater power and decision-making authority for the man. By contrast, same-sex couples appear to place greater value on achieving a fair distribution of household labor that is not linked to traditional roles and they often strive for power equality. However, like many heterosexual couples that espouse equality, not all same-sex couples actually achieve equal sharing of day-to-day household responsibilities or power equality.

- Heterosexual and same-sex couples display “striking similarities” in their reports of love and relationship satisfaction. “Like their heterosexual counterparts, gay and lesbian couples generally benefit when partners are similar in background, attitudes, and values” and when they both “perceive many rewards and few costs from their relationship.”

- “Among same-sex and heterosexual couples, there is wide variability in sexual frequency and a general decline in frequency as relationships continue over time. In the early stages of a relationship, gay male couples have sex more often than do other couples…. Lesbian couples report having sex less often than either heterosexual or gay male couples.”

- While having a sexually exclusive relationship tends to be associated with satisfaction in lesbian and heterosexual couples, this pattern is less common among gay male couples. Gay men are less likely than lesbians or heterosexuals to believe sexual exclusivity is important for their relationship, and are more likely to engage in sex with someone other than their partner. Gay male couples often explicitly negotiate the extent to which they will or won’t be sexually exclusive.

- “Lesbian, gay male, and heterosexual couples report a similar frequency of arguments and tend to disagree about similar topics, with finances, affection, sex, criticism, and household tasks heading the list.” The problem-solving skills of lesbian and gay couples appear to be at least as good as those of heterosexual couples. “As with heterosexual couples, happy lesbian and gay male couples are more likely than are unhappy couples to use constructive problem-solving approaches.”

- As with heterosexual couples, three main factors affect gay and lesbian partners’ psychological commitment to each other and the longevity of their relationship: (1) positive attraction forces, such as love and satisfaction, that make partners want to stay together; (2) the availability of alternatives to the current relationship, such as a more desirable partner; and (3) barriers that make it difficult for a person to leave the relationship, including investments that increase the psychological, emotional, or financial costs of ending a relationship, as well as moral or religious feelings of obligation or duty to one’s partner.

Of course, these conclusions are based on aggregate data and refer to general patterns in the population at large. Every couple — gay, lesbian, or heterosexual — is unique and doesn’t necessarily conform to all of the patterns described here.

As for Zelda and Dobie, propinquity apparently was important after all. They appeared as a married couple in the 1987 reunion movie Bring Me the Head of Dobie Gillis.

In real life, however, events took a different turn. The role of Zelda was played by Sheila James, now the Honorable Sheila James Kuehl, state senator for California’s 23rd District. When she joined the California Assembly in 1994, Sen. Kuehl became the first openly gay person elected to the California legislature. She has been a leading advocate for children, civil rights, the environment, and women’s issues.

* * * * *

Peplau and Fingerhut’s Annual Review of Psychology article has been published on-line (access is restricted to subscribers) and will be available in print in January.

Copyright © 2006 by Gregory M. Herek. All rights reserved.

Permalink ·

« Previous entries Next Page » Next Page »