June 26, 2009

Posted at 12:15 am (Pacific Time)

President Obama is under increasing pressure to begin dismantling the military’s “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” policy.

Last month the Palm Center at the University of California, Santa Barbara, released a new report showing how the President can legally suspend discharges of gay and lesbian personnel in advance of congressional action to permanently repeal DADT. (Full disclosure: I’m a coauthor of that report; my main contribution was to the section on how to effectively implement a new, nondiscriminatory policy.)

Earlier this week, 77 members of Congress sent an open letter to the President, urging him to suspend investigations and discharges of service members in the Armed Forces because of their sexual orientation. “By taking leadership of the important issue of Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell,” said Rep. Alcee Hastings (D-FL), “President Obama would allow openly gay and lesbian service members to continue serving their country and send a clear signal to Congress to initiate the legislative repeal process.”

And Wednesday, the Center for American Progress issued a five-step plan for repealing DADT that begins with an executive order suspending discharges.

What would be the political costs for the President and Congress of eliminating DADT?

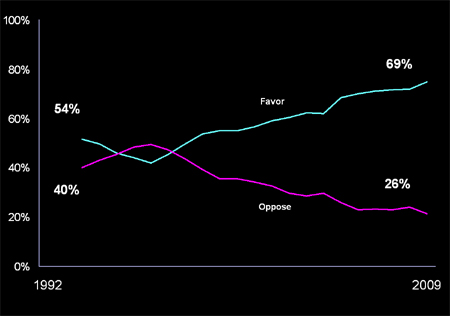

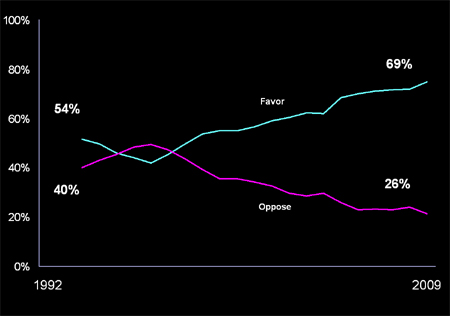

In terms of public approval, not much. In fact, repealing the policy might score points with voters. Poll data indicate that opposition to DADT has been steadily increasing in the years since it was first enacted, and that Americans now solidly support getting rid of it.

Public Opinion About DADT: Then and Now

Just before the 1992 Presidential election, by a margin of 54% to 40%, respondents to a national Harris survey supported “allowing gays and lesbians to serve in the military.” But the following year, as public debate about military policy took center stage, most polls showed public opposition to gay service members. (Also in 1993, pollsters began asking about service by openly gay and lesbian personnel.)

By 1994, however, after DADT had been enacted, public opinion again began to shift and a growing majority wanted to allow openly gay people to serve. As shown in the graph, this trend has continued to the present day. In the most recent poll – conducted last month by Gallup – 69% favored allowing openly gay people to serve. Only 26% were opposed.

This graph only includes polls that asked “Do you favor or oppose allowing openly gay men and lesbian women to serve in the military?” (or used similar wording). Other surveys that asked the question in different ways have obtained similar results.

In some surveys over the years, for example, the question about military service has been posed in terms of equal employment opportunities. With the question framed this way, the public has been even more likely to endorse military service by gay and lesbian personnel. As early as 1977, 51% of Gallup respondents said gay people “should be hired” for the armed forces, and that majority grew steadily over time. By 2005 (the last instance I could find when this question was posed in a national poll), 79% favored having the armed forces “hire” gay men and lesbians, while only 19% opposed it.

Other surveys have asked respondents to select from among three options: (a) allowing gay men and lesbians to serve openly, (b) allowing them to serve but without openly acknowledging their sexual orientation (the DADT approach), or (c) banning them entirely from military service. Over the past 15 years, relatively few respondents have advocated completely banning gay people from the military – never more than roughly 1 in 5. In July, 2007 (the most recent poll that asked this version of the question), only 15% said they wanted a total ban on gay personnel. In that same poll, 36% endorsed the DADT approach, whereas a plurality of 46% favored allowing gay people to serve openly. Compared to a similar poll in 2000, the 2007 results represented an increase of 6 points in favor of openly gay personnel, and a decrease of 7 points in support of a total ban.

Thus, regardless of how the question is asked, the long-term trend has been toward increasing support for openly gay service members.

The Unit Cohesion Argument: The Public Isn’t Buying It

Americans also have grown skeptical of the main rationale that has been offered for retaining DADT. In a 1993 Gallup/CNN/USA Today poll conducted shortly after Bill Clinton’s inauguration, 51% agreed that “admitting gays to the military would undermine discipline and morale” (46% disagreed).

But in a Quinnipiac University national poll this April, 58% disagreed that “allowing openly gay men and women to serve in the military would be divisive for the troops and hurt their ability to fight effectively.” In that same poll, a solid 56% favored repealing DADT whereas only 37% said it shouldn’t be repealed.

Support For A New Policy Is Broad-Based

A striking feature of the May 2009 Gallup poll is the breadth of support it reveals for a new military policy. Not surprisingly, self-described liberals are almost unanimous in supporting a nondiscriminatory policy (86%). But a solid majority of conservatives — 58% — also support openly gay and lesbian service members, as do 58% of Republicans and 60% of those who attend religious services weekly. Support has increased substantially in these groups since Gallup asked the same question in 2004 — by 6 points among Republicans, 11 points among regular churchgoers, and 12 points among conservatives.

Support is even higher among Democrats, Independents, and the less religious. And openly gay service members have solid support among both men and women, in all regions of the US (including 57% in the South), and in all age groups (even among those who are over 65, of whom 60% support a new policy).

The Bottom Line

This is a policy area in which the public is ahead of Congress and the President. There will certainly be an outcry from some far Right groups when President Obama suspends DADT and Congress overturns it permanently. In contrast to 1993, however, there appears to be a solid base of public support for a new policy that allows lesbian and gay Americans to serve their country without having to lie about who they are.

*Â Â Â Â *Â Â Â Â *Â Â Â Â *Â Â Â Â *

A slightly different version of this post appears on the Palm Center’s blog, Blueprints.

Copyright © 2009 by Gregory M. Herek. All rights reserved.

Permalink ·

June 16, 2009

Posted at 5:25 pm (Pacific Time)

Late last month, Gallup released findings from a new poll demonstrating that opposition to marriage equality is higher among American adults who say they don’t know anyone who is lesbian or gay.

The survey, which was conducted earlier in May, found that Americans oppose legalizing marriage between same-sex couples by 57% to 40% . That margin hasn’t changed notably since a previous Gallup poll about a year ago.

When the May sample was split into those who said they have a gay or lesbian friend, relative, or coworker (58% of the sample) and those who didn’t (40%), the differences in marriage attitudes were striking.

The latter group registered overwhelming opposition to marriage equality — 72% opposed it whereas only 27% favored it. Within this group, 63% said legalizing marriage for same-sex couples will change society for the worse, compared to six percent who said it will change society for the better. 30% believed it won’t have any effect on society.

By contrast, respondents reporting personal contact with a gay man or lesbian were almost evenly split — 49% supported marriage equality and 47% opposed it. They were also divided over whether marriage equality will change society for the worse (39% believed it will) or will have no effect (40% believed this). Only about one in five said it will change society for the better, but that percentage was more than three times higher than the comparable figure for respondents without a gay or lesbian friend, relative, or coworker.

Consistent with past research, the poll found that attitudes toward marriage equality are linked with a person’s political ideology, and that liberal respondents were more likely than their conservative counterparts to personally know gay people. But Gallup found that the correlation between personal contact and opinions about marriage remained significant, even when political ideology was statistically controlled.

But Why Only 49%?

The Gallup report prominently characterized the survey as showing that “Opposition to gay marriage [is] higher among those who do not know someone who is gay/lesbian.”

But we might well ask why there wasn’t greater support for marriage equality among poll respondents with gay or lesbian family or acquaintances. Why did only about half of that group support marriage rights? After all, research conducted over the past two decades has consistently shown that heterosexuals are less prejudiced against gay people if they know someone who is gay, and such prejudice is closely associated with opposition to marriage equality. (Data are lacking on how knowing a bisexual man or woman affects sexual prejudice among heterosexuals, but there’s reason to believe that the pattern is similar.)

My own reading of the research literature suggests that the strength of the correlation between prejudice and mere contact has diminished in recent years. A decade ago, knowing whether a heterosexual had a gay or lesbian friend or relative provided a very good indication of that person’s attitudes toward gay people in general. Today, personal contact remains a good predictor of prejudice, but it’s not as reliable as it once was.

I believe this diminution of the predictive power of mere contact may provide insight into what it is about contact that links it to nonprejudiced attitudes. My hypothesis is that the key variable isn’t — and never was — whether heterosexuals simply know a gay man or lesbian. Rather, what’s always been critical is the nature of that relationship. Perhaps the central variable is whether or not heterosexuals have talked with their gay friend or relative about the latter’s experiences and, in the course of those discussions, developed a better understanding of and more empathy for the situation of sexual minorities.

My hunch is that in the past, when most gay men and lesbians were highly selective about coming out, it was sufficient for researchers to simply ask heterosexual survey respondents whether they knew gay men or lesbians. If they had a gay friend or relative, more likely than not, they’d found out directly from that individual about her or his sexual orientation. Or, subsequent to finding out through some other means, they talked about it with her or him.

Today, by contrast, gay men and lesbians are more publicly visible. Many more heterosexuals probably have the experience of knowing that a relative, friend, or (especially) a coworker or neighbor is gay without ever having discussed it directly with that individual. Thus, knowing the details about a heterosexual person’s contact experiences is more important today than it was a few years (or decades) ago.

Some Data

This hypothesis is partly supported by data I collected in a 2005 telephone survey with a representative national sample of more than 2100 adults who identified as heterosexual. Along with questions about the nature and extent of their personal relationships with lesbian and gay individuals, respondents were asked a series of questions about their general feelings toward gay men and toward lesbians, their comfort or discomfort around both and, using a standard psychological attitude scale, their general attitudes toward them.

For purposes of analysis, I divided the sample into three groups: (1) those who said they had no gay or lesbian friends, acquaintances, or relatives as far as they knew, (2) those who knew at least one gay or lesbian person but hadn’t ever talked with that individual about being gay, and (3) those who had talked with a gay or lesbian friend or relative about the latter’s experiences as a sexual minority.

Compared to Group 1, Group 2 had more positive feelings, less discomfort, and generally more favorable attitudes toward gay men and lesbians. But Group 3 had significantly more positive views of lesbians and gay men than either Group 1 (those with no personal contact) or Group 2 (those with personal contact but no open discussion).

Implications

Combined with other survey findings that I’m still analyzing, these data suggest it often isn’t enough for heterosexuals to simply know that a member of their family or immediate social circle is gay or lesbian. In order for the experience to reduce their sexual prejudice, they also must communicate directly with their friend or relative about what it’s like to be gay.

But although such discussions probably play a key role in reducing sexual prejudice and increasing support for the civil rights of sexual minorities, they can be difficult. Not surprisingly, they don’t occur often enough. In a separate study (which is not yet published), I’ve found that most gay men and lesbians say they are out to their immediate family and close heterosexual friends, but many aren’t out to their extended family, coworkers, or heterosexual acquaintances. And many of those who are out never discuss their experiences with their family or friends.

These findings highlight the importance of assisting gay, lesbian, and bisexual people in having conversations — giving them support and helping them find the best way to talk with their heterosexual friends and family members about their lives and how they’re affected by issues like marriage equality. The Tell 3 Campaign is one strategy for promoting such discussions. If the marriage equality movement is going to succeed in changing public opinion, it will have to devote more resources to Tell 3 and other programs like it.

*Â Â Â *Â Â Â Â *Â Â Â Â *Â Â Â Â *

More information about my 2005 survey can be found in the following chapter:

Herek, G. M. (2009). Sexual stigma and sexual prejudice in the United States: A conceptual framework. In D.A. Hope (Ed.), Contemporary perspectives on lesbian, gay and bisexual identities: The 54th Nebraska Symposium on Motivation (pp. 65-111). New York: Springer.

Copyright © 2009 by Gregory M. Herek. All rights reserved.

Permalink ·

June 12, 2009

Posted at 12:22 pm (Pacific Time)

Larry Kurdek, one of the world’s leading social science researchers on lesbian and gay committed relationships, died yesterday in Ohio.

Over the past 25 years, Larry published dozens of important empirical and theoretical articles and chapters about gay and lesbian couples. Among other findings, his research demonstrated that the factors predicting relationship satisfaction, commitment, and stability are remarkably similar for both same-sex cohabiting couples and heterosexual married couples. His work was featured prominently in amicus briefs that the American Psychological Association (APA) filed in court cases challenging marriage laws in New Jersey, Connecticut, California, Iowa, and elsewhere. He received the 2003 Award for Distinguished Scientific Contributions from the Society for the Psychological Study of Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual Issues (APA Division 44).

Larry helped to craft the APA’s Resolution on Sexual Orientation and Marriage, in which the Association committed itself to “take a leadership role in opposing all discrimination in legal benefits, rights, and privileges against same-sex couples.” He also helped to develop the APA’s Resolution on Sexual Orientation, Parents, and Children, in which the Association went on record opposing “any discrimination based on sexual orientation in matters of adoption, child custody and visitation, foster care, and reproductive health services.”

Larry was a great lover of dogs. After receiving his cancer diagnosis, he decided to pursue research on the emotional bonds between people and their dogs. In 2008, he published a paper titled “Pet dogs as attachment figures” in the Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. In it, he documented similarities between the attachments people form with their dogs and those they form with other humans.

According to Gene Siesky, Larry’s partner, he passed away peacefully at home with his dogs by his side, just as he had wanted.

I first met Larry back in the 1980s. I got to see him only infrequently over the years, but we had an ongoing e-mail correspondence. He gave me lots of information and guidance about my own work and writing on marriage and relationships. During the time that I chaired the Scientific Review Committee for the Wayne F. Placek Awards, he was always willing to provide thoughtful reviews of proposals. And we sent each other condolences when we lost beloved dogs.

I’ll miss Larry as both a colleague and a friend. His premature passing is a great loss to the field of psychology and to everyone who supports marriage equality.

*Â Â Â Â *Â Â Â Â *Â Â Â Â *Â Â Â Â *

John Flach, Chair of the Psychology Department at Wright State University, shared these thoughts about Larry in an e-mail:

Larry had been battling cancer for several years. Up until a few weeks ago he was still working and working out. Those of you who know Larry, know that he was very dedicated to his work and his personal fitness.

Larry will be greatly missed by his colleagues in the Psych department. In many respects, Larry was the spiritual center of our department – helping us to always focus on quality.

Larry completed the Ph.D. at University of Illinois, Chicago in 1976 and began as an assistant professor at WSU that same year. He was promoted to Professor in 1984. He was an excellent teacher – teaching courses in statistics and developmental psychology. He was a leading researcher on commitment and satisfaction in family relationships with over 145 journal publications. And he was dedicated to serving the department, college, and university. For example, he was instrumental in developing the department bylaws.

I relied heavily on Larry’s support and guidance and will personally miss him very much.

*Â Â Â Â *Â Â Â Â *Â Â Â Â *Â Â Â Â *

A viewing and memorial service will be held this weekend at Newcomer Funeral Home, Beavercreek, Ohio. In lieu of flowers, contributions can be made to the Larry Kurdek Memorial Scholarship Fund in care of the Psychology Department at Wright State University, Dayton, Ohio.

Copyright © 2009 by Gregory M. Herek. All rights reserved.

Permalink ·