March 24, 2017

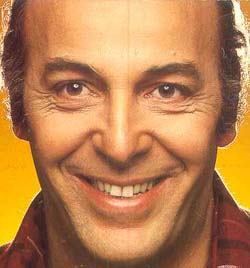

The Father of “Homophobia”: George Weinberg (1929-2017)

In 1972, private consensual sexual conduct between two adults of the same sex was illegal in all but a few states. Homosexuality was officially classified as a mental illness in the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. In a national opinion survey a few years earlier, 70 percent of respondents had said they believed homosexuals were more harmful than helpful to American life. Only 1 percent believed they were more helpful than harmful. From a long list of groups named in the survey questions, only Communists and atheists were considered harmful by more respondents than homosexuals.

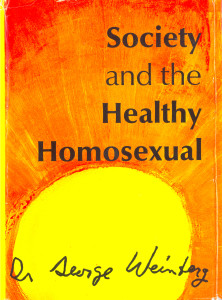

Against this backdrop, consider the audacity of George Weinberg, a heterosexual psychologist who published a book in 1972 titled Society and the Healthy Homosexual. Not only did Dr. Weinberg propose that homosexuals could be healthy, he also argued that a person’s mental health was impaired not by homosexuality but rather by society’s hostility toward it.

In his book’s opening sentence he asserted, “I would never consider a patient healthy unless he had overcome his prejudice against homosexuality.” Weinberg labeled that prejudice homophobia, which he defined as “the dread of being in close quarters with homosexuals — and in the case of homosexuals themselves, self-loathing.”

George Weinberg died of cancer on Monday, March 20, in Manhattan. He was 87 years old. What follows is a brief account of the origins of homophobia.

* * * * *

In his psychoanalytic training at Columbia University, Weinberg had learned the then-current view that homosexuality is a pathology and a homosexual patient’s problems — whether they occurred in personal relationships, work, or any other facet of life — ultimately stem from her or his sexual orientation.

Weinberg had known some gay people previously. And after he began practicing as a psychotherapist, some long-time friends disclosed to him that they were gay. He experienced dissonance between his professional training and his personal experience.

“I valued these friends for their encompassing, loving vision of literature, their gentleness of spirit, their subtlety,” he later wrote. “It was hard to be one of the chosen people, the ‘heteros,’ when so many people whom I admired were not invited to the party.”

It didn’t take him long to resolve the conflict. By the mid-1960s, Weinberg was an active supporter of New York’s fledgling gay movement and an opponent of psychiatric attempts to “cure” homosexuality.

The concept of homophobia came to him in 1965, around the time he gave an invited speech, titled “The Dangers of Psychoanalysis,” at the September conference of East Coast Homophile Organizations (ECHO). As he reflected on his professional colleagues’ and heterosexual friends’ strongly negative personal reactions to being around a homosexual in nonclinical settings “it came to me with utter clarity that this was a phobia.” Preparing the speech, he later said, “set me to thinking about ‘What’s wrong with those people?'”

During a 1998 interview, he told me “I found that no matter who they met or how they reacted, I could not get them to accept homosexuals in any way, and that none of them had any homosexual friends.” It occurred to him that these reactions could be described as a phobia.

Weinberg’s circle of gay friends at the time included Jack Nichols and Lige Clarke, the activists who first used homophobia in print. They wrote a weekly column, “The Homosexual Citizen,” for Screw magazine. Screw, described by one historian as a “raunchy sex tabloid,” was published in New York by Al Goldstein, and had a circulation of approximately 150,000 by mid-1969. “The Homosexual Citizen” was a first: a regular feature directed at gay readers in a widely circulated, decidedly heterosexual publication. Goldstein gave Nichols and Clarke control over the content of their columns but he composed the headlines.

Drawing from their conversations with Weinberg, Nichols and Clarke wrote about homophobia in their May 23, 1969 column, to which Goldstein assigned the headline “He-Man Horse Shit.” They used homophobia to refer to heterosexuals’ fears that others might believe they are homosexual. Such fear, they wrote, limited men’s experiences by declaring off limits such “sissified” things as poetry, art, movement, and touching. Although the Screw column appears to have been the first time homophobia appeared in print, Nichols always credited Weinberg with originating the term.

Homophobia soon achieved currency in popular speech, as evidenced by its appearance a few months later in a Time Magazine article.

Weinberg’s first published use of the word came in 1971 in a July 19th article he wrote for Gay, Nichols’ newsweekly. Titled “Words for the New Culture,” the essay foreshadowed Society and the Healthy Homosexual. In it, he described homophobia’s consequences, emphasizing its strong linkage to enforcement of male gender norms:

“The cost of any phobia is inhibition spreading to a whole circle of acts considered dangerously close to the illicit activity. In this case, acts that might be construed as invitational to homosexual feelings, or that are reminiscent of homosexual acts, are shunned. Since homosexuality is feared more in men than in women, this results in marked differences in permissiveness toward the sexes. For instance, a great many men are withheld from embracing each other or kissing each other, or longing for each other’s company, as openly as women do. It is expected that men will not see beauty in the physical forms of other men, or enjoy it, whereas women may openly express admiration for the beauty of other women. Ramifications of this phobic fear extend even to parent-child relationships. Millions of fathers feel that it would not befit them to kiss their sons affectionately or embrace them, whereas mothers can kiss and embrace their daughters as well as their sons. It is expected that men, even lifetime friends, will not sit as close together on a couch while talking earnestly as women may; they will not look into each other’s faces as steadily or as fondly.”

The essay also made it clear that Weinberg considered homophobia a form of prejudice directed by one group at another:

“When a phobia incapacitates a person from engaging in activities considered decent by society, the person himself is the sufferer. But here the phobia appears as antagonism directly toward a particular group of people. Inevitably, it leads to disdain toward the people themselves, and to mistreatment of them. The phobia in operation is a prejudice, and this means we can widen our understanding by considering the phobia from the point of view of its being a prejudice and then uncovering its motives.”

The same year that “Words for the New Culture” was published also saw the first appearance of homophobia in an academic journal. Kenneth Smith, a graduate student writing his thesis under Weinberg’s supervision, published a brief research report on its psychological correlates.

Society and the Healthy Homosexual was published the following year.

* * * * *

Homophobia neatly challenged entrenched thinking about the “problem” of homosexuality. It encapsulated the rejection, hostility, and invisibility that North American homosexual men and women had experienced throughout the twentieth century. It shifted the locus of the “problem” from gay men and lesbians to heterosexuals’ intolerance. In doing so, it questioned the legitimacy of society’s rules about gender, especially for males. The very existence of a term suggesting that rejection and hostility were not natural human reactions to homosexuality but instead were symptoms of an underlying psychological disorder subverted a central assumption of heterosexual society.

Homophobia has important limitations, at least for social and behavioral scientists. And, of course, Weinberg was not the only advocate to challenge traditional thinking about homosexuality. Society might have become sensitized to antigay prejudice without the term homophobia.

But by creating this simple, memorable label and thereby helping to define prejudice based on sexual orientation as a problem for individuals and for society, Weinberg made a profound and enduring contribution to sexual minority rights.

* * * * *

Portions of this post are based on my article Beyond “homophobia”: Thinking about sexual stigma and prejudice in the twenty-first century, published in Sexuality Research and Social Policy (2004). Other sources include:

- Ayyar, R. (2002, November 1). George Weinberg: Love is conspiratorial, deviant, and magical, Gay Today.

- Nichols, J. (1997, February 3). George Weinberg, Ph.D., Gay Today. Retrieved from

- Nichols, J. (2002). George Weinberg. In V. L. Bullough (Ed.), Before Stonewall: Activists for gay and lesbian rights in historical context (pp. 351-360). New York: Harrington Park Press.

- Weinberg, G. (1972). Society and the healthy homosexual. New York: St. Martin’s.