March 24, 2017

Posted at 8:34 pm (Pacific Time)

In 1972, private consensual sexual conduct between two adults of the same sex was illegal in all but a few states. Homosexuality was officially classified as a mental illness in the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. In a national opinion survey a few years earlier, 70 percent of respondents had said they believed homosexuals were more harmful than helpful to American life. Only 1 percent believed they were more helpful than harmful. From a long list of groups named in the survey questions, only Communists and atheists were considered harmful by more respondents than homosexuals.

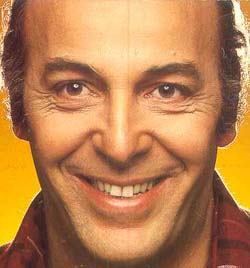

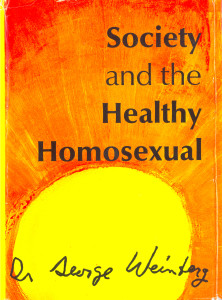

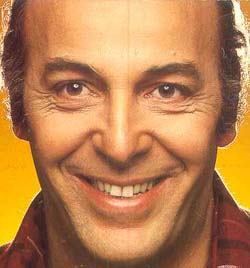

Against this backdrop, consider the audacity of George Weinberg, a heterosexual psychologist who published a book in 1972 titled Society and the Healthy Homosexual. Not only did Dr. Weinberg propose that homosexuals could be healthy, he also argued that a person’s mental health was impaired not by homosexuality but rather by society’s hostility toward it.

In his book’s opening sentence he asserted, “I would never consider a patient healthy unless he had overcome his prejudice against homosexuality.” Weinberg labeled that prejudice homophobia, which he defined as “the dread of being in close quarters with homosexuals — and in the case of homosexuals themselves, self-loathing.”

George Weinberg died of cancer on Monday, March 20, in Manhattan. He was 87 years old. What follows is a brief account of the origins of homophobia.

* * * * *

In his psychoanalytic training at Columbia University, Weinberg had learned the then-current view that homosexuality is a pathology and a homosexual patient’s problems — whether they occurred in personal relationships, work, or any other facet of life — ultimately stem from her or his sexual orientation.

Weinberg had known some gay people previously. And after he began practicing as a psychotherapist, some long-time friends disclosed to him that they were gay. He experienced dissonance between his professional training and his personal experience.

“I valued these friends for their encompassing, loving vision of literature, their gentleness of spirit, their subtlety,” he later wrote. “It was hard to be one of the chosen people, the ‘heteros,’ when so many people whom I admired were not invited to the party.”

It didn’t take him long to resolve the conflict. By the mid-1960s, Weinberg was an active supporter of New York’s fledgling gay movement and an opponent of psychiatric attempts to “cure” homosexuality.

The concept of homophobia came to him in 1965, around the time he gave an invited speech, titled “The Dangers of Psychoanalysis,” at the September conference of East Coast Homophile Organizations (ECHO). As he reflected on his professional colleagues’ and heterosexual friends’ strongly negative personal reactions to being around a homosexual in nonclinical settings “it came to me with utter clarity that this was a phobia.” Preparing the speech, he later said, “set me to thinking about ‘What’s wrong with those people?'”

During a 1998 interview, he told me “I found that no matter who they met or how they reacted, I could not get them to accept homosexuals in any way, and that none of them had any homosexual friends.” It occurred to him that these reactions could be described as a phobia.

Weinberg’s circle of gay friends at the time included Jack Nichols and Lige Clarke, the activists who first used homophobia in print. They wrote a weekly column, “The Homosexual Citizen,” for Screw magazine. Screw, described by one historian as a “raunchy sex tabloid,” was published in New York by Al Goldstein, and had a circulation of approximately 150,000 by mid-1969. “The Homosexual Citizen” was a first: a regular feature directed at gay readers in a widely circulated, decidedly heterosexual publication. Goldstein gave Nichols and Clarke control over the content of their columns but he composed the headlines.

Drawing from their conversations with Weinberg, Nichols and Clarke wrote about homophobia in their May 23, 1969 column, to which Goldstein assigned the headline “He-Man Horse Shit.” They used homophobia to refer to heterosexuals’ fears that others might believe they are homosexual. Such fear, they wrote, limited men’s experiences by declaring off limits such “sissified” things as poetry, art, movement, and touching. Although the Screw column appears to have been the first time homophobia appeared in print, Nichols always credited Weinberg with originating the term.

Homophobia soon achieved currency in popular speech, as evidenced by its appearance a few months later in a Time Magazine article.

Weinberg’s first published use of the word came in 1971 in a July 19th article he wrote for Gay, Nichols’ newsweekly. Titled “Words for the New Culture,” the essay foreshadowed Society and the Healthy Homosexual. In it, he described homophobia’s consequences, emphasizing its strong linkage to enforcement of male gender norms:

“The cost of any phobia is inhibition spreading to a whole circle of acts considered dangerously close to the illicit activity. In this case, acts that might be construed as invitational to homosexual feelings, or that are reminiscent of homosexual acts, are shunned. Since homosexuality is feared more in men than in women, this results in marked differences in permissiveness toward the sexes. For instance, a great many men are withheld from embracing each other or kissing each other, or longing for each other’s company, as openly as women do. It is expected that men will not see beauty in the physical forms of other men, or enjoy it, whereas women may openly express admiration for the beauty of other women. Ramifications of this phobic fear extend even to parent-child relationships. Millions of fathers feel that it would not befit them to kiss their sons affectionately or embrace them, whereas mothers can kiss and embrace their daughters as well as their sons. It is expected that men, even lifetime friends, will not sit as close together on a couch while talking earnestly as women may; they will not look into each other’s faces as steadily or as fondly.”

The essay also made it clear that Weinberg considered homophobia a form of prejudice directed by one group at another:

“When a phobia incapacitates a person from engaging in activities considered decent by society, the person himself is the sufferer. But here the phobia appears as antagonism directly toward a particular group of people. Inevitably, it leads to disdain toward the people themselves, and to mistreatment of them. The phobia in operation is a prejudice, and this means we can widen our understanding by considering the phobia from the point of view of its being a prejudice and then uncovering its motives.”

The same year that “Words for the New Culture” was published also saw the first appearance of homophobia in an academic journal. Kenneth Smith, a graduate student writing his thesis under Weinberg’s supervision, published a brief research report on its psychological correlates.

Society and the Healthy Homosexual was published the following year.

* * * * *

Homophobia neatly challenged entrenched thinking about the “problem” of homosexuality. It encapsulated the rejection, hostility, and invisibility that North American homosexual men and women had experienced throughout the twentieth century. It shifted the locus of the “problem” from gay men and lesbians to heterosexuals’ intolerance. In doing so, it questioned the legitimacy of society’s rules about gender, especially for males. The very existence of a term suggesting that rejection and hostility were not natural human reactions to homosexuality but instead were symptoms of an underlying psychological disorder subverted a central assumption of heterosexual society.

Homophobia has important limitations, at least for social and behavioral scientists. And, of course, Weinberg was not the only advocate to challenge traditional thinking about homosexuality. Society might have become sensitized to antigay prejudice without the term homophobia.

But by creating this simple, memorable label and thereby helping to define prejudice based on sexual orientation as a problem for individuals and for society, Weinberg made a profound and enduring contribution to sexual minority rights.

* * * * *

Portions of this post are based on my article Beyond “homophobia”: Thinking about sexual stigma and prejudice in the twenty-first century, published in Sexuality Research and Social Policy (2004). Other sources include:

- Ayyar, R. (2002, November 1). George Weinberg: Love is conspiratorial, deviant, and magical, Gay Today.

- Nichols, J. (1997, February 3). George Weinberg, Ph.D., Gay Today. Retrieved from

- Nichols, J. (2002). George Weinberg. In V. L. Bullough (Ed.), Before Stonewall: Activists for gay and lesbian rights in historical context (pp. 351-360). New York: Harrington Park Press.

- Weinberg, G. (1972). Society and the healthy homosexual. New York: St. Martin’s.

Copyright © 2017 by Gregory M. Herek. All rights reserved.

Permalink ·

September 1, 2016

Posted at 8:52 pm (Pacific Time)

September 2, 2016, marks the 109th birth anniversary of Dr. Evelyn Hooker, the psychologist whose pioneering research helped to establish that homosexuality is not inherently linked to mental illness. Here’s a link to an earlier post about Dr. Hooker’s life and work.

Copyright © 2016 by Gregory M. Herek. All rights reserved.

Permalink ·

February 3, 2015

Posted at 12:01 pm (Pacific Time)

Not so long ago, homosexuality was triply stigmatized.

Throughout much of the 20th century, in addition to being condemned as a sin and prosecuted as a crime, it was assumed by the mental health professions to be an illness.

Although that assumption was never based on valid scientific research, the stigma attached to homosexuality impelled untold numbers of lesbian, gay, and bisexual people to seek a cure for their condition. Others were coerced into treatment after being arrested or hospitalized.

Psychologists and psychiatrists used a variety of techniques on them, ranging from talk therapy to electroshock, aversive conditioning, lobotomies, hormone injections, hysterectomies, and castrations.

None were effective.

Meanwhile, new research was challenging orthodox beliefs about homosexuality and prompting some mental health professionals and researchers to question the validity of the sickness model.

Alfred Kinsey’s studies revealed that same-sex attraction and behavior were much more common than had been widely believed. Clellan Ford and Frank Beach showed that homosexual behavior was common across human societies and in other species.

And Evelyn Hooker documented the existence of well-adjusted gay men. She also demonstrated that experts in the “diagnosis” of homosexuality could not distinguish between the Rorschach protocols of well-functioning gay and heterosexual men at a level better than chance.

The larger society was also changing. By the 1960s, gay and lesbian activists were challenging the notion that they were mentally ill.

Psychiatric and psychological orthodoxy proved unable to withstand the critical scrutiny that these developments brought. On December 15, 1973, millions of people suddenly found themselves free of mental illness when the American Psychiatric Association’s Board of Directors voted to remove homosexuality as a diagnosis from its Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM).

It was arguably the biggest mass cure in the modern history of mental health.

Then, meeting in late January of 1975 – almost exactly 40 years ago – the American Psychological Association (APA) Council of Representatives voted to support the psychiatrists’ action, affirming that:

“Homosexuality per se implies no impairment in judgment, stability, reliability, or general social and vocational capabilities.”

This complete reversal in the status accorded to homosexuality by the mental health profession’s two largest and most influential organizations was to have a huge impact.

Gay, lesbian, and bisexual people would no longer have to grow up assuming they are sick. Reputable psychologists and psychiatrists would no longer tell them they can and should become heterosexual. Because a characteristic that isn’t an illness doesn’t need treatment, the raison d’etre for attempting to cure homosexuality vanished.

Nearly all therapists eventually abandoned their efforts to make gay people straight. New therapeutic approaches were developed that affirm the value of gay, lesbian, and bisexual identities and same-sex relationships while assisting sexual minorities in coping with the challenges created by societal stigma. These approaches are now integral to the education, training, and practice of psychologists and other mental health professionals.

*Â Â Â Â *Â Â Â Â *Â Â Â Â *Â Â Â Â *

But the significance of this year’s 40th anniversary extends further. The APA’s 1975 resolution also urged mental health professionals

“to take the lead in removing the stigma of mental illness that has long been associated with homosexual orientations.”

Thus, the Association committed itself to advocacy, lobbying, and educational efforts on behalf of sexual minorities. It has since followed through by promoting research and communicating scientific and clinical knowledge about sexual orientation to the courts, elected officials, policy makers, educators, and the general public.

Notably, these efforts have included filing amicus briefs in more than 40 major federal and state court cases involving the rights of sexual minorities. Roughly half of those cases involved legal recognition of same-sex couples. Others addressed state sodomy laws, discrimination, restrictions on military service, parenting rights, and related issues.

Drawing from empirical research, the APA briefs have explained important facts about sexual orientation:

*Â Â Â Â *Â Â Â Â *Â Â Â Â *Â Â Â Â *

In April, when the U.S. Supreme Court hears oral arguments for four marriage equality cases, the APA will file another amicus brief summarizing current scientific knowledge and professional opinion about sexual orientation, committed intimate relationships, parenting, and related topics.

In doing so, the Association will continue to honor its pledge to take the lead in “removing the stigma.”

*Â Â Â Â *Â Â Â Â *Â Â Â Â *Â Â Â Â *

A version of this post also appears on the APA’s blog, Psychology Benefits Society.

The APA amicus briefs are available at: http://www.apa.org/about/offices/ogc/amicus/index-issues.aspx

Copyright © 2015 by Gregory M. Herek. All rights reserved.

Permalink ·

September 16, 2014

Posted at 1:00 am (Pacific Time)

Last week, the 7th Circuit Court of Appeals upheld lower court rulings striking down anti-marriage laws in Indiana and Wisconsin. Even those of us who aren’t legal scholars can find good reading in Judge Richard Posner’s written opinion, which skewered the states’ arguments against marriage equality.

As a social scientist, I was pleased that his legal analysis was informed by data from social and behavioral research. And I was gratified that he referenced some of my own work.

Early in his 40-page decision, Judge Posner wrote,

“We begin our detailed analysis of whether prohibiting same-sex marriage denies equal protection of the laws by noting that Indiana and Wisconsin … are discriminating against homosexuals by denying them a right that these states grant to heterosexuals, namely the right to marry an unmarried adult of their choice. And there is little doubt that sexual orientation, the ground of the discrimination, is an immutable (and probably an innate, in the sense of in-born) characteristic rather than a choice. Wisely, neither Indiana nor Wisconsin argues otherwise.” (p. 9, my emphasis)

The evidence he cited in support of this assertion included materials from the American Psychological Association and a paper on which I was the lead author, describing findings from a survey I conducted with a nationally representative sample of lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults.

This blog post is about the research and the context in which I conducted it.

*Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â *Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â *Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â *Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â *

Early research on sexual minority subcultures in the United States tended to focus on gay men. And the researchers often reported that most gay men felt they hadn’t chosen their sexual orientation. For example, in his 1951 book, The Homosexual in America: A Subjective Approach, sociologist Edward Sagarin (writing under the pseudonym Donald Webster Cory) wrote:

“This does not mean that sexual inversion [homosexuality] is voluntary, and that one need only exercise good judgment and will-power in order to overcome it or to choose some other pathway. Not at all. It is entirely involuntary and beyond control, because one did not choose to want to be homosexual.” (p. 183)

And psychologist Evelyn Hooker, in her 1965 paper, Male Homosexuals and Their “Worlds” (in Judd Marmor’s edited book, Sexual Inversion: The Multiple Roots of Homosexuality), reported from her ethnographic observations of gay male communities:

“One of the important features of homosexual subcultures is the pattern of beliefs or the justification system. Central to it is the explanation of why they are homosexuals, involving the question of choice. The majority believe either that they were born as homosexuals or that familial factors operating very early in their lives determined the outcome. In any case, homosexuality is believed to be a fate over which they have no control and in which they have no choice.” (p. 102)

In recent years, religious conservatives have strongly disputed this view, and the argument that homosexuality is a sinful choice has achieved considerable prominence in their public rhetoric. In the 1990s, they mounted media campaigns promoting the notion that people can and should stop being gay. The director of one of these ex-gay campaigns told the New York Times that its goal was to strike at the assumption that homosexuality was immutable and that gay people therefore need protection under anti-discrimination laws.

Not surprisingly, public opinion reflects this dimension of the culture wars. Heterosexuals’ attitudes toward lesbians and gay men are reliably correlated with their beliefs about choice. Antigay heterosexuals are likely to assert that homosexuality is a choice, whereas unprejudiced heterosexuals are likely to believe that sexual orientation is inborn or otherwise not chosen. (As discussed below, the question of whether heterosexuals choose their orientation is rarely asked.)

*Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â *Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â *Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â *Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â *

In the 1990s, I was surprised to discover that, despite all the debate and heated rhetoric, relatively little empirical research had directly examined how people perceive their own sexual orientation.

Indirect evidence for a lack of choice was available. For example, most participants in the Kinsey studies of the 1940s and 1950s reported they had experienced sexual attraction only to one sex (men or women) throughout their entire lives; but the Kinsey team did not ask directly about perceptions of choice.

Illuminating research was conducted by sociologist Vera Whisman, who set out to study lesbians and gay men who said they had chosen their sexual orientation. However, as she reported in her book, Queer By Choice, most of her sample did not experience their patterns of sexual attractions as a choice. Those who were “queer by choice” were typically referring to choosing their sexual behaviors and the labels and identities they adopted for themselves.

Otherwise, anecdotal and autobiographical accounts were available and a few studies reported relevant questionnaire data from small samples. But as best I could tell, no large-scale studies had asked people whether they perceived their own sexual orientation (whether hetero-, homo-, or bisexual) as a choice.

*Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â *Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â *Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â *Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â *

This lack of data prompted me to begin asking about choice in my own research.

Based on the available evidence, I expected to find that many – probably most – gay men didn’t perceive their sexual orientation to be a choice.

For women, however, I thought the pattern might be different. Many feminists argued that lesbianism is a choice women can (and should) make for themselves. And in some early studies, gay men tended to report having been aware of their homosexuality at an earlier age than lesbians, which might be evidence of a gender difference in the experience of choice.

These and other patterns led me to tentatively hypothesize that lesbians would be more likely than gay men to report they experienced some degree of choice about their sexual orientation.

In an exploratory study during the 1990s with a relatively small community sample that included 125 gay and lesbian adults, these hypotheses were supported. My colleagues and I found that most of the gay men (80%) said they had no choice at all about their sexual orientation. The proportion of lesbians who said they had no choice was smaller, but still a majority (62%).

While these findings were interesting, the sample was small. I subsequently decided to ask a similar question in two survey studies with larger and more representative samples that also included enough bisexual women and men to permit meaningful analyses of their responses.

In the first of those surveys, we collected questionnaire data from 2,259 gay, lesbian, and bisexual adults in the greater Sacramento area. One questionnaire item was, “How much choice do you feel that you had about being lesbian/bisexual?” [for men the wording was “gay]/bisexual”]. The 5 response options were “no choice at all,” “very little choice,” “some choice,” “a fair amount of choice,” and “a great deal of choice.”

The results weren’t dramatically different from those we obtained in the pilot study: 87% of the gay men reported they experienced “no choice at all” or “very little choice” about their sexual orientation. Once again, women perceived having more choice than men. Even so, most lesbians (nearly 70%) reported having little or no choice.

It is perhaps not surprising that bisexuals reported feeling they had more choice about their sexual orientation. Nevertheless, nearly 59% of bisexual men and 45% of bisexual women said they experienced little or no choice. Another 15% and 20%, respectively, said they had only “some choice.”

This study’s sample was large but it wasn’t a probability sample, i.e., one that is representative of the population at large. We had recruited the participants mainly through Northern California lesbian, gay, and bisexual community organizations and at community events, most of them in the Sacramento area. People who weren’t active in the community or weren’t open about their sexual orientation were probably underrepresented.

I subsequently had the opportunity to assess how well these findings fit the population as a whole when I surveyed a nationally representative sample of self-identified lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults. We asked them “How much choice do you feel you had about being lesbian?” [Or gay or queer or bisexual or homosexual, depending on the term they had previously said they preferred for describing themselves.] Four response options were available: “no choice at all,” “a small amount of choice,” “a fair amount of choice,” and “a great deal of choice.”

The responses of gay men and lesbians were strikingly similar to those we obtained from the Sacramento-area community sample: 88% of the gay men reported “no choice at all” about being gay, with another 6.9% saying they experienced “a small amount of choice.” Only 5% reported they experienced “a fair amount” or “a great deal” of choice. Among lesbians, 68.4% reported no choice, and another 15.2% reported experiencing a small amount of choice; only 16% experienced a fair amount or a great deal of choice.

Thus, 95% of gay men and 84% of lesbians reported experiencing little or no choice about their sexual orientation. This is the finding Judge Posner cited last week in his opinion.

In contrast to the community study, a majority of bisexuals in the national sample reported having little or no choice about their sexual orientation, although they were less likely than gay men and lesbians to say they experienced no choice at all. Among bisexual men, 38.3% said they experienced no choice, and another 22.4% experienced a small amount of choice, a total of 60.7%. Among bisexual women, the numbers were 40.6% and 15.2%, respectively, a total of 55.8%.

None of these surveys explicitly defined the term choice, so we don’t know whether respondents interpreted it as referring to their pattern of attractions, their sexual behaviors, their identity, or some other facet of sexual orientation. Based on Vera Whisman’s research, cited above, it seems likely that most were referring to the amount of choice they experience in their sexual attractions and desires.

*Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â *Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â *Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â *Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â *

What about heterosexuals? Do they perceive their sexual orientation as a choice?

To the best of my knowledge, no published research based on a probability sample of heterosexual adults reports data that directly answer this question. I intended to ask it in a national survey I conducted in the 1990s, but was dissuaded from doing so by other members of my research team. They convinced me the question would create problems during data collection because most heterosexuals simply wouldn’t know how to answer it.

This asymmetry in who can answer the choice question can be understood as a reflection of sexual stigma. One manifestation of stigma is the widespread assumption that heterosexuality is normal and unproblematic. Few heterosexuals are ever asked what made them straight, and most have probably never thought about the origin of their own attractions to the other sex.

Homosexuality, by contrast, is viewed as problematic. Nonheterosexuals are routinely asked what made them “that way” and, in the course of coming out, they often ask themselves this question. Even when a scientific study evenhandedly examines the origins of all sexual orientations, its subject matter is typically characterized as what causes people to be gay or bisexual.

In this context of stigma, it is perhaps not surprising that I encountered some raised eyebrows when I initially shared my findings about perceptions of choice with other researchers – not so much because of the numbers, but simply because I had asked the question.

Some assumed that documenting how people perceive their sexual orientation would be the basis for arguing that gay, lesbian, and bisexual people shouldn’t be persecuted because “it’s not their fault” – they never chose to be “that way.” This argument is perceived (often correctly) as implicitly suggesting that (a) being lesbian, gay, or bisexual is a defect, and (b) if people did choose to be anything other than heterosexual, they would deserve to be discriminated against.

*Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â *Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â *Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â *Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â *

But although Judge Posner’s opinion takes up the question of choice – as did Judge Vaughn Walker, who cited the same research in his decision overturning California’s Proposition 8 – he doesn’t treat homosexuality as a defect. Nor does he suggest that gay, lesbian, and bisexual people would deserve to be persecuted if they freely chose their sexual orientation.

However, Judge Posner recognizes that lesbian, gay, and bisexual people constitute an identifiable minority group defined by an immutable characteristic that is irrelevant to a person’s ability to contribute to society. Consequently, any attempt by the state to discriminate against them must serve some important government objective.

And, as he concluded, the rationale offered by Wisconsin and Indiana for their laws denying marriage rights to same-sex couples, “is so full of holes that it cannot be taken seriously…. The discrimination against same-sex couples is irrational, and therefore unconstitutional…” (pp. 7-8).

*         *         *         *         *

Here are the bibliographic sources for my studies, described above.

Herek, G. M., Cogan, J. C., Gillis, J. R., & Glunt, E. K. (1998). Correlates of internalized homophobia in a community sample of lesbians and gay men. Journal of the Gay and Lesbian Medical Association, 2(1), 17-25.

Herek, G. M., Gillis, J. R., & Cogan, J. C. (2009). Internalized stigma among sexual minority adults: Insights from a social psychological perspective. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 56, 32-43.

Herek, G. M., Norton, A. T., Allen, T. J., & Sims, C. L. (2010). Demographic, psychological, and social characteristics of self-identified lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults in a U.S. probability sample. Sexuality Research and Social Policy, 7, 176-200.

A brief introduction to sampling terminology and methods is available on my website.

Copyright © 2014 by Gregory M. Herek. All rights reserved.

Permalink ·

September 2, 2014

Posted at 12:01 am (Pacific Time)

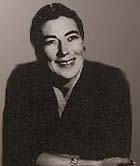

Today is the 107th anniversary of the birth of Dr. Evelyn Hooker, the psychologist who is widely credited with helping to establish that homosexuality is not inherently linked to mental illness.

In the course of her remarkable life, Dr. Hooker surmounted many of the barriers faced by women who sought an academic career in the 20th century.

In the course of her remarkable life, Dr. Hooker surmounted many of the barriers faced by women who sought an academic career in the 20th century.

She was born Evelyn Gentry on September 2, 1907, to a poor farm family in North Platte, Nebraska. The sixth of nine children, she received her early education in one-room schoolhouses on the Nebraska prairie, followed by high school in Sterling, Colorado. She subsequently earned baccalaureate and master’s degrees at the University of Colorado.

She wanted to apply to the doctoral psychology program at Yale but her University of Colorado department chairman (himself a Yale graduate) refused to recommend a woman. Instead, she entered the graduate program at Johns Hopkins University, receiving her Ph.D. in 1932.

She taught at the Maryland College for Women and then at Whittier College. While at Whittier, she received a fellowship to study psychotherapy for a year in Germany. As Hitler was ascending to power, she resided with a Jewish family in Berlin. While in Europe, she also visited Russia shortly after Stalin’s purge of 1938. Those experiences in totalitarian states further deepened her interest in working for social justice and human rights.

Whittier fired Dr. Hooker and several of her colleagues for their liberal political beliefs. She was subsequently hired by UCLA as an adjunct faculty member. According to the department chairman, she was relegated to that status because the Psychology Department faculty (all but three of whom were men) were unwilling to appoint another woman to a tenure-track position.

In 1951, she married Edward Niles Hooker, a distinguished UCLA professor of English and the man she called her “true love.” He died suddenly in 1957, a loss that deeply pained her.

Dr. Hooker is best known for her psychological research in the 1950s and 1960s with gay men.

Her studies were innovative in several important respects. Rather than simply accepting the conventional wisdom that homosexuality is a pathology, she used the scientific method to test this assumption. And rather than studying homosexual psychiatric patients, she recruited a sample of gay men who were functioning normally in society.

For her best known study, published in 1957 in The Journal of Projective Techniques, she recruited 30 homosexual males and 30 heterosexual males through community organizations in the Los Angeles area. The two groups were matched for age, IQ, and education. None of the men were in therapy at the time of the study.

She administered three projective tests to the men — the Rorschach inkblot test, the Thematic Apperception Test (TAT), and the Make-A-Picture-Story (MAPS) Test). Then she asked outside experts to use the test data to rate each man’s mental health. Although today it seems like an obvious safeguard against bias, Dr. Hooker’s was the first published study to utilize raters who did not know the sexual orientation of the study participants.

Using the Rorschach data, two of the independent experts evaluated the men’s overall adjustment using a 5-point scale. They classified two-thirds of the heterosexuals and two-thirds of the homosexuals in the three highest categories of adjustment.

Hooker presented the judges with the 60 Rorschach protocols in random order and asked them to identify each man’s sexual orientation. Only six of the homosexual men and six of the heterosexual men were correctly identified by both judges. She later gave the judges another opportunity, this time presenting them with matched pairs of protocols, one from a homosexual man and one from a heterosexual. Only 12 of the 30 pairs elicited correct responses from both judges.

A third expert used the TAT and MAPS protocols to evaluate the men’s psychological adjustment. As with the Rorschach responses, the adjustment ratings of the homosexuals and heterosexuals did not differ significantly.

Dr. Hooker concluded from her data that homosexuality is not a clinical entity and that homosexuality is not inherently associated with psychopathology. Her findings have since been replicated by other investigators using a variety of research methods.

In retrospect, we can see that Dr. Hooker’s main hypothesis — that no group differences in psychological distress should exist between heterosexual and homosexual samples — actually applied too strict a test. We know today that some members of stigmatized groups manifest elevated rates of psychological distress — for example, because of the stress imposed on them by social ostracism, harassment, discrimination, and violence. Such correlations don’t mean that group membership is itself a pathology.

By documenting that well-adjusted homosexuals not only existed but in fact were numerous, Dr. Hooker’s research demonstrated that the illness model had no scientific basis. She helped to lay the foundation for the American Psychiatric Association’s 1973 decision to remove homosexuality from its Diagnostic & Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, and for the American Psychological Association’s subsequent commitment to removing the stigma that has historically been attached to homosexuality.

Dr. Hooker died at her Santa Monica home on November 18, 1996. Her pioneering research and remarkable life were honored with awards from numerous professional organizations, including the American Psychological Association, and many advocacy and community groups.

* * * *

For more information, see the 1992 Oscar-nominated documentary, Changing Our Minds The Story of Dr. Evelyn Hooker.

A biographical sketch and a selected bibliography of Dr. Hooker’s publications can be found on my website.

* * * * *

Postscript. Although homosexuality has not been classified as a mental disorder in the United States for decades, the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) still lists several diagnoses related to homosexuality (although not homosexuality itself) as pathological. For example, “ego-dystonic” sexual orientation, which was removed from the DSM in the 1980s, remains in the ICD.

In preparation for the upcoming 11th edition of the ICD, the World Health Organization created a Working Group on the Classification of Sexual Disorders and Sexual Health to review these diagnoses. In a report released this summer, the Working Group, headed by Prof. Susan Cochran of UCLA, recommended that all of them be eliminated.

The Working Group’s recommendations will be reviewed by the ministers of health from more than 170 WHO countries, including Russia, Uganda, Nigeria, and other nations where sexual stigma is enshrined in law.

* * * * *

This entry is an expanded and updated version of a 2008 Beyond Homophobia post.

Copyright © 2014 by Gregory M. Herek. All rights reserved.

Permalink ·

September 2, 2008

Posted at 10:20 am (Pacific Time)

Today is the 101st anniversary of Dr. Evelyn Hooker’s birth.

Dr. Hooker, the psychologist who is widely credited with helping to establish that homosexuality is not inherently linked to mental illness, was born September 2, 1907, in North Platte, Nebraska. She was the sixth of nine children.

In the course of her remarkable life, Dr. Hooker surmounted many of the barriers faced by women who sought an academic career in the 20th century. She is best known for her psychological research in the 1950s and 1960s with gay men.

In the course of her remarkable life, Dr. Hooker surmounted many of the barriers faced by women who sought an academic career in the 20th century. She is best known for her psychological research in the 1950s and 1960s with gay men.

Her studies were innovative in several important respects. Rather than simply accepting the conventional wisdom that homosexuality is a pathology, she used the scientific method to test this assumption. And rather than studying homosexual psychiatric patients, she recruited a sample of gay men who were functioning normally in society.

For her best known study, published in 1957 in The Journal of Projective Techniques, she recruited 30 homosexual males and 30 heterosexual males through community organizations in the Los Angeles area. The two groups were matched for age, IQ, and education. None of the men were in therapy at the time of the study.

She administered three projective tests to the men — the Rorschach inkblot test, the Thematic Apperception Test (TAT), and the Make-A-Picture-Story (MAPS) Test). Then she asked outside experts with no prior knowledge of the men’s sexual orientation to use the test data to rate their mental health. Although today it seems like an obvious safeguard against bias, Dr. Hooker’s was the first published study to utilize raters who were “blind” to the sexual orientation of the study participants.

Using the Rorschach data, two of the independent experts evaluated the men’s overall adjustment using a 5-point scale. They classified two-thirds of the heterosexuals and two-thirds of the homosexuals in the three highest categories of adjustment. When asked to identify which Rorschach protocols were obtained from homosexuals, the experts couldn’t do it at a level better than chance.

A third expert used the TAT and MAPS protocols to evaluate the men’s psychological adjustment. As with the Rorschach responses, the adjustment ratings of the homosexuals and heterosexuals did not differ significantly.

Dr. Hooker concluded from her data that homosexuality is not a clinical entity and that homosexuality is not inherently associated with psychopathology. Her findings have since been replicated by other investigators using a variety of research methods.

In retrospect, we can see that Dr. Hooker’s main hypothesis — that no group differences in psychological distress should exist between heterosexual and homosexual samples — actually applied too strict a test. We know today that some members of stigmatized groups manifest elevated rates of psychological distress because of the stress imposed on them by social ostracism, harassment, discrimination, and violence. Such patterns don’t indicate that the group is inherently disturbed.

Nevertheless, by demonstrating that well-adjusted homosexuals not only existed but in fact were numerous, Dr. Hooker’s research demonstrated that the illness model had no scientific basis. She helped to lay the foundation for the American Psychiatric Association’s 1973 decision to remove homosexuality from its Diagnostic & Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, and for the American Psychological Association’s subsequent commitment to removing the stigma that has historically been attached to homosexuality.

Dr. Hooker died at her Santa Monica home on November 18, 1996. Her pioneering research and remarkable life were honored with awards from numerous professional organizations, including the American Psychological Association, and many advocacy and community groups.

*Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â *Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â *Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â *Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â *

For more information, see the 1992 Oscar-nominated documentary, Changing Our Minds The Story of Dr. Evelyn Hooker.

A biographical sketch and a selected bibliography of Dr. Hooker’s publications can be found at my UC Davis website.

Copyright © 2008 by Gregory M. Herek. All rights reserved.

Permalink ·

July 23, 2008

Posted at 11:02 am (Pacific Time)

Today the Military Personnel Subcommittee of the House Armed Services Committee holds hearings on “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell.”

The congressional hearings come as Democrats increasingly discuss repealing the policy under a new Administration, and in the wake of a July ABC News/Washington Post Poll in which 75% of respondents said that “homosexuals who DO publicly disclose their sexual orientation should be allowed to serve in the military.” (78% said those who DON’T disclose their sexual orientation should be allowed to serve.)

The hearings also follow the recent release of a report by a team of retired senior military officers that concluded the ban on openly gay service members is counterproductive and should end, as well as a public statement signed by more than 50 retired generals and admirals that calls on Congress to repeal DADT.

With these signs of quickening movement toward eliminating the military’s discriminatory personnel policy, I’d like to be able to discuss the social science research relevant to the policy.

However, there isn’t much to say that is new.

Revisiting the Social Science Data

To be sure, new studies have been released that consider issues related to privacy, unit cohesion, and the experiences of other countries that have integrated sexual minorities into their militaries. I’ve discussed some of this work in previous posts. The Michael D. Palm Center website at the University of California, Santa Barbara, is also an excellent resource for such research.

But the conclusions of the newer research don’t differ much from those of past studies.

Thus, it seems appropriate to revisit a previous set of hearings in which the House Armed Services Committee heard about social science research relevant to military personnel policy. They were held in May of 1993 and were chaired by Rep. Ron Dellums (D-CA).

I was invited to testify before the Committee on behalf of the American Psychological Association and five other professional organizations (the American Psychiatric Association, the National Association of Social Workers, the American Counseling Association, the American Nursing Association, and the Sex Information and Education Council of the United States).

What follows is the bulk of my oral statement (with some introductory and background material omitted):

Mr. Chairman and members of the Committee, I am pleased to have the opportunity to appear before you today to provide testimony on the policy implications of lifting the ban on homosexuals in the military….

My written testimony to the Committee summarizes the results of an extensive review of the relevant published research from the social and behavioral sciences. That review is lengthy. However, I can summarize its conclusions in a few words: The research data show that there is nothing about lesbians and gay men that makes them inherently unfit for military service, and there is nothing about heterosexuals that makes them inherently unable to work and live with gay people in close quarters.

….I would like to address two questions that have been raised repeatedly in the current discussion surrounding the military ban on service by gay men and lesbians. The first question is whether lesbians and gay men are inherently unfit for service. In the current debate, some consensus seems to have been reached that gay people are just as competent, just as dedicated, and just as patriotic as their heterosexual counterparts. However, questions still are raised concerning whether the presence of openly gay military personnel would create a heightened risk for sexual harassment, favoritism, or fraternization.

Obviously, data are not available to address these questions directly because the current policy has made collection of such data impossible in the military. However, based on research conducted with civilians, as well as reports from quasi-military organizations in the United States (such as police and fire departments) and the armed forces of other countries, there is no reason to expect that gay men and lesbians would be any more likely than heterosexuals to engage in sexual harassment or other prohibited conduct. We know that a homosexual orientation is not associated with impaired psychological functioning; it is not in any way a mental illness. In addition, there is no valid scientific evidence to indicate that gay men and lesbians are less able than heterosexuals to control their sexual or romantic urges, to refrain from the abuse of power, to obey rules and laws, to interact effectively with others, or to exercise good judgment in handling authority….

The second question I would like to address is whether unit cohesion and morale would be harmed if personnel known to be gay were allowed to serve. Would heterosexual personnel refuse to work and live in close quarters with lesbian or gay male service members? This question reflects a recognition that stigma leads many heterosexuals to hold false stereotypes about lesbians and gay men and unwarranted prejudices against them.

As with the first question, we do not currently have data that directly answer questions about morale and cohesion. We do know, however, that heterosexuals are fully capable of establishing close interpersonal relationships with gay people and that as many as one-third of the adult heterosexual population in the U.S. has already done so. We also know that heterosexuals who have a close ongoing relationship with a gay man or a lesbian tend to express favorable and accepting attitudes toward gay people as a group. And it appears that ongoing interpersonal contact in a supportive environment where common goals are emphasized, and prejudice is clearly unacceptable, is likely to foster positive feelings toward gay men and lesbians. Thus, the assumption that heterosexuals cannot overcome their prejudices toward gay people is a mistaken one.

In summary, neither heterosexuals nor homosexuals appear to possess any characteristics that would make them inherently incapable of functioning under a nondiscriminatory military policy. In my written testimony, I have offered a number of recommendations for implementing such a policy. I would like to mention five of the principal recommendations here.

The military should:

- establish clear norms that sexual orientation is irrelevant to performing one’s duty and that everyone should be judged on her or his own merits;

- eliminate false stereotypes about gay men and lesbians through education and sensitivity training for all personnel;

- set uniform standards for public conduct that apply equally to heterosexual and homosexual personnel;

- deal with sexual harassment as a form of conduct rather than as a characteristic of a class of people, and establish that all sexual harassment is unacceptable regardless of the genders or sexual orientations involved;

- take a firm and highly publicized stand that violence against gay personnel is unacceptable and will be punished quickly and severely; attach stiff penalties to antigay violence perpetrated by military personnel.

Undoubtedly, implementing a new policy will involve challenges that will require careful and planned responses from the military leadership. This has been true for racial and gender integration, and it will be true for integration of open lesbians and gay men. The important point is that such challenges can be successfully met. The real question for debate is whether the military, the government, and the country as a whole are willing to meet them.

Mr. Chairman, thank you for the opportunity to testify today. I will be happy to answer any questions that members of the Committee might have.

From 1993 to 2008

That was in 1993. Today, as then, the real question is not whether sexual minorities can be successfully integrated into the military. The social science data answered this question in the affirmative then, and do so even more clearly now.

Rather, the issue is whether the United States is willing to repudiate its current practice of antigay discrimination and address the challenges associated with a new policy.

The growing opposition to DADT among military veterans and the public indicate that we finally may be ready to take up this challenge.

*Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â *Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â *Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â *Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â *

The full text of my 1993 oral statement before the House Armed Services Committee can be read on my website.

Copyright © 2008 by Gregory M. Herek. All rights reserved.

Permalink ·

« Previous entries Next Page » Next Page »

In the course of her remarkable life, Dr. Hooker surmounted many of the barriers faced by women who sought an academic career in the 20th century.

In the course of her remarkable life, Dr. Hooker surmounted many of the barriers faced by women who sought an academic career in the 20th century. In the course of her remarkable life, Dr. Hooker surmounted many of the barriers faced by women who sought an academic career in the 20th century. She is best known for her psychological research in the 1950s and 1960s with gay men.

In the course of her remarkable life, Dr. Hooker surmounted many of the barriers faced by women who sought an academic career in the 20th century. She is best known for her psychological research in the 1950s and 1960s with gay men.