June 17, 2015

Why Has Public Opinion About Marriage Equality Changed?

Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsberg has been quoted as saying the Court’s 1973 Roe v. Wade decision went “too far, too fast.”

Her comment has sometimes been cited in speculation that the Court won’t rule that people have a constitutional right to marry a same-sex partner because the Justices are reluctant to get too far ahead of public opinion.

However, public opinion may be well ahead of the Court in this arena. As we await a ruling in the Orbergefell marriage equality cases, it’s a good time to reflect on current public sentiment about marriage rights for same-sex couples, and how and why it has shifted over the last two decades.

Public Opinion Today

Last week, the Pew Research Center reported that 57% of the respondents in their latest national survey (most of whom presumably were heterosexual) said they support “allowing gays and lesbians to marry legally.” Only 39% were opposed.

Compare this to a 2001 Pew poll in which the numbers were reversed: 57% opposed marriage equality and only 35% supported it.

A recent Gallup poll showed the same remarkable turnaround: 60% of their respondents now endorse the statement that “marriages between same-sex couples should be recognized by the law as valid, with the same rights as traditional marriage.”

As with the Pew data, earlier Gallup surveys revealed a quite different pattern. In 2005, 59% opposed marriage equality and only 37% supported it. Still earlier, in 1996, marriage rights for same-sex couples were opposed by more than two thirds (68%) of Gallup respondents, with only 27% in support.

Polling data on marriage equality have been somewhat confusing because different surveys have yielded different numbers. As early as 2010, a few already showed a majority of Americans favoring marriage equality. And even today some still show less than half of the public supporting marriage equality.

This variability is largely explained by methodological differences among the polling organizations, according to a meta-analysis by UCLA political scientist Andrew Flores that was recently published in Public Opinion Quarterly.

When Dr. Flores combined the data from more than 130 different polls, controlling statistically for variations in question wording and “house effects” (i.e., differences among polling organizations in how they collect and analyze their data), he found a clear trend: Support for marriage equality has increased fairly steadily since 1996, with a majority of the public endorsing it by 2014.

The trend of shifting attitudes isn’t limited to marriage equality. We see it as well in public opinion about adoption rights, the ability of same-sex couples to be good parents, protection from employment discrimination, and other issues relevant to law and policy. And it is also evidenced by a steady increase in favorable attitudes toward lesbian and gay people in recent years. (Attitudes toward bisexual women and men have probably changed as well, but few polls have included questions designed to specifically tap those attitudes.)

Change has occurred in nearly every demographic group, although it’s more evident in some groups than in others. For example, marriage equality support has increased more among Democrats and Independents than Republicans. But Republicans’ support has nevertheless been increasing as well.

Is the Shift Generational or Individual?

How can we explain these seismic shifts over a relatively brief time span?

They’re often attributed to ongoing population turnover. According to this explanation, individuals aren’t changing their opinions. Rather, change results from older generations dying out and younger ones taking their place. On average, older people are less likely than their younger counterparts to support marriage equality or express favorable attitudes toward sexual minorities. As time passes and younger generations come of age, their attitudes become more dominant in society as a whole.

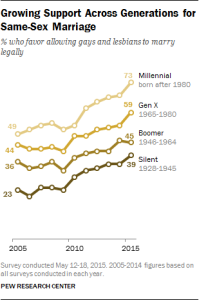

This pattern of generational replacement is evident when polling data are broken down by age groups. As shown in the Pew data, for example, support for marriage equality is lowest among adults born during the Depression Era but increases steadily in each successive generation. Baby Boomers are more supportive than their elders, GenXers are more supportive than Boomers, and Milliennials show the strongest support of any age group.

But generational replacement is only part of the story. The Pew graph shows that opinions have also been shifting within each age group. In other words, attitude change isn’t happening only in the population as a whole; heterosexual individuals have been changing their minds about sexual minorities, and at a rapid pace.

In fact, individual change is the primary force behind the big shifts in public opinion. When researchers Gregory Lewis and Lanae Hatalsky combined data from more than 128,000 respondents in nearly 100 national surveys conducted between 2004 and 2011, they found that only 25% of the shift in overall support for marriage equality during those 8 years could be attributed to generational replacement. Most of the change – 75% of it – resulted from individuals who once opposed or were undecided about marriage equality coming to support it.

Why Are People Changing Their Minds?

Why have so many individual Americans changed their minds? There’s no single answer to this question; people have different reasons. But we can see a common thread running through those reasons if we assume that people generally adopt attitudes and opinions to meet their important psychological needs and to feel good about themselves. When any particular attitude stops serving these purposes, it’s susceptible to change.

For example, heterosexual people whose sense of self is grounded mainly in their personal value system – whether deriving from religion, politics, ethics, or other sources – are likely to express attitudes that serve to affirm those values. Whether they support or oppose marriage equality, their attitude functions to solidify their sense of personal identity and increase their feelings of self-worth. If they come to see their stance on marriage equality as inconsistent with key aspects of their value system, however, they may be open to change.

A 2013 Pew survey, for example, found that 28% of those who endorsed marriage equality said they hadn’t always held that view. When asked what made them change their minds, roughly one third cited values — e.g., their own moral and religious beliefs or their support for equality. For them, being true to those values came to mean expressing support for marriage equality.

Other heterosexual people have especially strong needs for social acceptance and affiliation. The main motivation underlying their marriage equality opinions is their desire to secure approval and support from friends, family, and other important groups. If group norms change, however, clinging to the old attitude may block them from meeting those affiliation needs. As support for marriage equality increasingly becomes the norm throughout much of the United States, people seeking their group’s approval are more and more likely to get it by changing their attitudes to conform with the trend.

About one sixth of respondents in the 2013 Pew survey attributed their new-found endorsement of marriage equality to their perception that social acceptance of it is inevitable. For at least some of them, changing their attitudes may have allowed them to continue to enjoy group acceptance in a changing world.

Attitudes can also function to help people make sense of their own past experiences, including their interactions with people from groups other than their own. Having an unpleasant encounter with a lesbian, gay, or bisexual person may lead heterosexuals to hold negative feelings toward all sexual minorities. Conversely, good experiences can generalize to a positive attitude toward the entire group and issues that affect it.

Interestingly, it turns out that heterosexuals’ personal contact with lesbian, gay, or bisexual people usually results in more positive attitudes, not only toward the specific person involved, but also toward sexual minorities as a group. Having a friend or relative who is gay, lesbian, or bisexual can be a potent motivator for heterosexuals to change their opinions.

We see evidence of this pattern in the 2013 Pew poll. About one third of the participants who had come to support marriage equality cited their personal experiences with gay or lesbian friends, family members, or acquaintances as the reason why.

As I’ve discussed in previous blog posts, personal contact appears to be especially influential when it includes open discussion of what it’s like to be lesbian, gay, or bisexual. Such discussions can lead heterosexuals to think about sexual minorities in a new way and to rethink the connections between their personal values and their attitudes toward sexual minorities. And when heterosexuals see that their own family or friendship circle includes sexual minorities, the desire to maintain their social ties can motivate them to rethink their attitudes.

The functional approach I’ve used to organize this discussion focuses on individual psychology. But shifts in public opinion about marriage equality aren’t simply a matter of what goes on inside people’s heads. The larger culture’s beliefs and norms make possible the relationship between particular attitudes and specific psychological needs. As cultural institutions have changed in recent years, so have the ways in which heterosexuals’ attitudes toward marriage equality and sexual minorities are linked to their values, worldview, group memberships, and personal relationships. (For a more sociological perspective on attitude change, see this post from The Conversation.com.)

Back to Justice Ginsburg

Perhaps another quotation from Justice Ginsburg is more fitting to the current moment than her “too far, too fast” comment.

Earlier this week, she displayed a clear understanding of how and why public attitudes toward lesbian, gay, and bisexual people have changed when she cited the power of personal contact and coming out in advancing sexual minority rights:

“People looked around … and it was my next-door neighbor, of whom I was very fond, my child’s best friend, even my child…. They are people we know and we love and we respect, and they are part of us…. Discrimination began to break down very rapidly once they no longer hid in a corner or in a closet.”

If, as many observers expect, she and a majority of her colleagues on the Court affirm same-sex couples’ right to marry, they won’t be getting ahead of public opinion. Rather, they’ll be following the lead of the American people.