March 24, 2017

Posted at 8:34 pm (Pacific Time)

In 1972, private consensual sexual conduct between two adults of the same sex was illegal in all but a few states. Homosexuality was officially classified as a mental illness in the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. In a national opinion survey a few years earlier, 70 percent of respondents had said they believed homosexuals were more harmful than helpful to American life. Only 1 percent believed they were more helpful than harmful. From a long list of groups named in the survey questions, only Communists and atheists were considered harmful by more respondents than homosexuals.

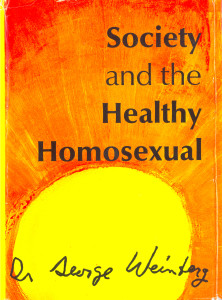

Against this backdrop, consider the audacity of George Weinberg, a heterosexual psychologist who published a book in 1972 titled Society and the Healthy Homosexual. Not only did Dr. Weinberg propose that homosexuals could be healthy, he also argued that a person’s mental health was impaired not by homosexuality but rather by society’s hostility toward it.

In his book’s opening sentence he asserted, “I would never consider a patient healthy unless he had overcome his prejudice against homosexuality.” Weinberg labeled that prejudice homophobia, which he defined as “the dread of being in close quarters with homosexuals — and in the case of homosexuals themselves, self-loathing.”

George Weinberg died of cancer on Monday, March 20, in Manhattan. He was 87 years old. What follows is a brief account of the origins of homophobia.

* * * * *

In his psychoanalytic training at Columbia University, Weinberg had learned the then-current view that homosexuality is a pathology and a homosexual patient’s problems — whether they occurred in personal relationships, work, or any other facet of life — ultimately stem from her or his sexual orientation.

Weinberg had known some gay people previously. And after he began practicing as a psychotherapist, some long-time friends disclosed to him that they were gay. He experienced dissonance between his professional training and his personal experience.

“I valued these friends for their encompassing, loving vision of literature, their gentleness of spirit, their subtlety,” he later wrote. “It was hard to be one of the chosen people, the ‘heteros,’ when so many people whom I admired were not invited to the party.”

It didn’t take him long to resolve the conflict. By the mid-1960s, Weinberg was an active supporter of New York’s fledgling gay movement and an opponent of psychiatric attempts to “cure” homosexuality.

The concept of homophobia came to him in 1965, around the time he gave an invited speech, titled “The Dangers of Psychoanalysis,” at the September conference of East Coast Homophile Organizations (ECHO). As he reflected on his professional colleagues’ and heterosexual friends’ strongly negative personal reactions to being around a homosexual in nonclinical settings “it came to me with utter clarity that this was a phobia.” Preparing the speech, he later said, “set me to thinking about ‘What’s wrong with those people?'”

During a 1998 interview, he told me “I found that no matter who they met or how they reacted, I could not get them to accept homosexuals in any way, and that none of them had any homosexual friends.” It occurred to him that these reactions could be described as a phobia.

Weinberg’s circle of gay friends at the time included Jack Nichols and Lige Clarke, the activists who first used homophobia in print. They wrote a weekly column, “The Homosexual Citizen,” for Screw magazine. Screw, described by one historian as a “raunchy sex tabloid,” was published in New York by Al Goldstein, and had a circulation of approximately 150,000 by mid-1969. “The Homosexual Citizen” was a first: a regular feature directed at gay readers in a widely circulated, decidedly heterosexual publication. Goldstein gave Nichols and Clarke control over the content of their columns but he composed the headlines.

Drawing from their conversations with Weinberg, Nichols and Clarke wrote about homophobia in their May 23, 1969 column, to which Goldstein assigned the headline “He-Man Horse Shit.” They used homophobia to refer to heterosexuals’ fears that others might believe they are homosexual. Such fear, they wrote, limited men’s experiences by declaring off limits such “sissified” things as poetry, art, movement, and touching. Although the Screw column appears to have been the first time homophobia appeared in print, Nichols always credited Weinberg with originating the term.

Homophobia soon achieved currency in popular speech, as evidenced by its appearance a few months later in a Time Magazine article.

Weinberg’s first published use of the word came in 1971 in a July 19th article he wrote for Gay, Nichols’ newsweekly. Titled “Words for the New Culture,” the essay foreshadowed Society and the Healthy Homosexual. In it, he described homophobia’s consequences, emphasizing its strong linkage to enforcement of male gender norms:

“The cost of any phobia is inhibition spreading to a whole circle of acts considered dangerously close to the illicit activity. In this case, acts that might be construed as invitational to homosexual feelings, or that are reminiscent of homosexual acts, are shunned. Since homosexuality is feared more in men than in women, this results in marked differences in permissiveness toward the sexes. For instance, a great many men are withheld from embracing each other or kissing each other, or longing for each other’s company, as openly as women do. It is expected that men will not see beauty in the physical forms of other men, or enjoy it, whereas women may openly express admiration for the beauty of other women. Ramifications of this phobic fear extend even to parent-child relationships. Millions of fathers feel that it would not befit them to kiss their sons affectionately or embrace them, whereas mothers can kiss and embrace their daughters as well as their sons. It is expected that men, even lifetime friends, will not sit as close together on a couch while talking earnestly as women may; they will not look into each other’s faces as steadily or as fondly.”

The essay also made it clear that Weinberg considered homophobia a form of prejudice directed by one group at another:

“When a phobia incapacitates a person from engaging in activities considered decent by society, the person himself is the sufferer. But here the phobia appears as antagonism directly toward a particular group of people. Inevitably, it leads to disdain toward the people themselves, and to mistreatment of them. The phobia in operation is a prejudice, and this means we can widen our understanding by considering the phobia from the point of view of its being a prejudice and then uncovering its motives.”

The same year that “Words for the New Culture” was published also saw the first appearance of homophobia in an academic journal. Kenneth Smith, a graduate student writing his thesis under Weinberg’s supervision, published a brief research report on its psychological correlates.

Society and the Healthy Homosexual was published the following year.

* * * * *

Homophobia neatly challenged entrenched thinking about the “problem” of homosexuality. It encapsulated the rejection, hostility, and invisibility that North American homosexual men and women had experienced throughout the twentieth century. It shifted the locus of the “problem” from gay men and lesbians to heterosexuals’ intolerance. In doing so, it questioned the legitimacy of society’s rules about gender, especially for males. The very existence of a term suggesting that rejection and hostility were not natural human reactions to homosexuality but instead were symptoms of an underlying psychological disorder subverted a central assumption of heterosexual society.

Homophobia has important limitations, at least for social and behavioral scientists. And, of course, Weinberg was not the only advocate to challenge traditional thinking about homosexuality. Society might have become sensitized to antigay prejudice without the term homophobia.

But by creating this simple, memorable label and thereby helping to define prejudice based on sexual orientation as a problem for individuals and for society, Weinberg made a profound and enduring contribution to sexual minority rights.

* * * * *

Portions of this post are based on my article Beyond “homophobia”: Thinking about sexual stigma and prejudice in the twenty-first century, published in Sexuality Research and Social Policy (2004). Other sources include:

- Ayyar, R. (2002, November 1). George Weinberg: Love is conspiratorial, deviant, and magical, Gay Today.

- Nichols, J. (1997, February 3). George Weinberg, Ph.D., Gay Today. Retrieved from

- Nichols, J. (2002). George Weinberg. In V. L. Bullough (Ed.), Before Stonewall: Activists for gay and lesbian rights in historical context (pp. 351-360). New York: Harrington Park Press.

- Weinberg, G. (1972). Society and the healthy homosexual. New York: St. Martin’s.

Copyright © 2017 by Gregory M. Herek. All rights reserved.

Permalink ·

September 1, 2016

Posted at 8:52 pm (Pacific Time)

September 2, 2016, marks the 109th birth anniversary of Dr. Evelyn Hooker, the psychologist whose pioneering research helped to establish that homosexuality is not inherently linked to mental illness. Here’s a link to an earlier post about Dr. Hooker’s life and work.

Copyright © 2016 by Gregory M. Herek. All rights reserved.

Permalink ·

September 2, 2008

Posted at 10:20 am (Pacific Time)

Today is the 101st anniversary of Dr. Evelyn Hooker’s birth.

Dr. Hooker, the psychologist who is widely credited with helping to establish that homosexuality is not inherently linked to mental illness, was born September 2, 1907, in North Platte, Nebraska. She was the sixth of nine children.

In the course of her remarkable life, Dr. Hooker surmounted many of the barriers faced by women who sought an academic career in the 20th century. She is best known for her psychological research in the 1950s and 1960s with gay men.

In the course of her remarkable life, Dr. Hooker surmounted many of the barriers faced by women who sought an academic career in the 20th century. She is best known for her psychological research in the 1950s and 1960s with gay men.

Her studies were innovative in several important respects. Rather than simply accepting the conventional wisdom that homosexuality is a pathology, she used the scientific method to test this assumption. And rather than studying homosexual psychiatric patients, she recruited a sample of gay men who were functioning normally in society.

For her best known study, published in 1957 in The Journal of Projective Techniques, she recruited 30 homosexual males and 30 heterosexual males through community organizations in the Los Angeles area. The two groups were matched for age, IQ, and education. None of the men were in therapy at the time of the study.

She administered three projective tests to the men — the Rorschach inkblot test, the Thematic Apperception Test (TAT), and the Make-A-Picture-Story (MAPS) Test). Then she asked outside experts with no prior knowledge of the men’s sexual orientation to use the test data to rate their mental health. Although today it seems like an obvious safeguard against bias, Dr. Hooker’s was the first published study to utilize raters who were “blind” to the sexual orientation of the study participants.

Using the Rorschach data, two of the independent experts evaluated the men’s overall adjustment using a 5-point scale. They classified two-thirds of the heterosexuals and two-thirds of the homosexuals in the three highest categories of adjustment. When asked to identify which Rorschach protocols were obtained from homosexuals, the experts couldn’t do it at a level better than chance.

A third expert used the TAT and MAPS protocols to evaluate the men’s psychological adjustment. As with the Rorschach responses, the adjustment ratings of the homosexuals and heterosexuals did not differ significantly.

Dr. Hooker concluded from her data that homosexuality is not a clinical entity and that homosexuality is not inherently associated with psychopathology. Her findings have since been replicated by other investigators using a variety of research methods.

In retrospect, we can see that Dr. Hooker’s main hypothesis — that no group differences in psychological distress should exist between heterosexual and homosexual samples — actually applied too strict a test. We know today that some members of stigmatized groups manifest elevated rates of psychological distress because of the stress imposed on them by social ostracism, harassment, discrimination, and violence. Such patterns don’t indicate that the group is inherently disturbed.

Nevertheless, by demonstrating that well-adjusted homosexuals not only existed but in fact were numerous, Dr. Hooker’s research demonstrated that the illness model had no scientific basis. She helped to lay the foundation for the American Psychiatric Association’s 1973 decision to remove homosexuality from its Diagnostic & Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, and for the American Psychological Association’s subsequent commitment to removing the stigma that has historically been attached to homosexuality.

Dr. Hooker died at her Santa Monica home on November 18, 1996. Her pioneering research and remarkable life were honored with awards from numerous professional organizations, including the American Psychological Association, and many advocacy and community groups.

*Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â *Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â *Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â *Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â Â *

For more information, see the 1992 Oscar-nominated documentary, Changing Our Minds The Story of Dr. Evelyn Hooker.

A biographical sketch and a selected bibliography of Dr. Hooker’s publications can be found at my UC Davis website.

Copyright © 2008 by Gregory M. Herek. All rights reserved.

Permalink ·

July 4, 2008

Posted at 12:49 pm (Pacific Time)

I’m not going to put a lesbian in a position like that….

If you want to call me a bigot, fine.”

—Jesse Helms, in response to President Clinton’s 1993 nomination of Roberta Achtenberg as an assistant secretary at the Department of Housing and Urban Development.

Future students of 20th-century US history may puzzle over a section of the 1990 Hate Crimes Statistics Act. After mandating the federal government’s annual collection of data about “crimes that manifest evidence of prejudice based on race, religion, sexual orientation, or ethnicity,” the Act includes the following passage:

“SEC. 2.

(a) Congress finds that:

- the American family life is the foundation of American Society,

- Federal policy should encourage the well-being, financial security, and health of the American family,

- schools should not de-emphasize the critical value of American family life.

(b) Nothing in this Act shall be construed, nor shall any funds appropriated to carry out the purpose of the Act be used, to promote or encourage homosexuality”

This section of the Act is the legacy of Jesse Helms, who died today at the age of 86.

When the Hate Crimes Statistics Act was being considered by the Senate, Helms played a leading role in efforts to block it because it included antigay violence among the crimes to be monitored by law enforcement personnel. Aware of the bill’s popularity and having failed to remove sexual orientation from it, Helms attempted to thwart its passage by introducing an amendment that its supporters would find unacceptable but politically difficult to vote down.

The Helms amendment would have added the following language to the bill:

“It is the sense of the Senate that:

- the homosexual movement threatens the strength and survival of the American family as the basic unit of society;

- State sodomy laws should be enforced because they are in the best interest of public health;

- the Federal Government should not provide discrimination protections on the basis of sexual orientation; and

- school curriculums should not condone homosexuality as an acceptable lifestyle in American society.”

Such tactics were typical of Helms, who regularly used his parliamentary skills to get his own way in the Senate. On this occasion, however, he was outmaneuvered by Senators Paul Simon (D-IL) and Orrin Hatch (R-UT), who proposed alternative language that was less antigay.

The Simon-Hatch amendment was approved before Helms’ amendment was considered, thus providing political cover for senators. By supporting the Simon-Hatch language, they could safely vote against Helms’ amendment without being labeled pro-gay and anti-family.

And that’s why the Hate Crimes Statistics Act includes statements about “the American family” and denials that it was intended to “promote or encourage homosexuality.”

Helms’ failure at preventing passage of the Hate Crimes Statistics Act was unusual. His mastery of Senate procedure, coupled with lawmakers’ fear of appearing pro-gay, frequently allowed him to succeed in enacting his anti-gay agenda.

When the US was first confronting the AIDS epidemic in the 1980s, for example, Helms was instrumental in preventing the government from funding effective prevention programs among gay and bisexual men. The Senate twice endorsed his amendments prohibiting federal funds for AIDS education materials that “promote or encourage, directly or indirectly, homosexual activities.” By constricting the scope of risk-reduction education, Helms’ actions were widely believed to have contributed to the epidemic’s rapid spread.

Throughout his 30-year tenure in the US Senate, Helms was consistently associated with antigay stands. Given this fact, as well as his longstanding opposition to racial equality and the race-baiting tactics he used in election campaigns throughout his career, it is a fairly easy matter to accept his invitation to label him a bigot.

Personal bigotry aside, however, Helms’ legacy includes the many institutional manifestations of heterosexism that he was able to implement during his years in the Senate. Through the laws he sponsored and those he helped to defeat, he created real hardships for sexual minorities while also fostering sexual prejudice in American society. And his efforts probably contributed to the spread of HIV in the United States and the infection and deaths of many gay and bisexual men.

On this Independence Day and the occasion of Jesse Helms’ death, it is fitting to note how personal bigotry combined with political power can enable one politician to do so much harm to so many people.

And, recalling the general unwillingness of elected leaders to stand up to Jesse Helms’ antigay campaigns over the years, it is appropriate to reflect upon the words attributed to Edmund Burke: “The only thing necessary for the triumph of evil is for good men to do nothing.”

Copyright © 2008 by Gregory M. Herek. All rights reserved.

Permalink ·

June 3, 2008

Posted at 3:36 pm (Pacific Time)

Charles Moskos, the military sociologist who helped to craft the “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” policy, died of cancer on May 31.

Moskos, a professor of sociology at Northwestern University from 1966 until his retirement in 2003, is credited with helping to design AmeriCorps and was an expert on racial integration in the military. His books include The Military: More Than Just a Job?, Black Leadership and Racial Integration the Army Way, and The Postmodern Military. He received numerous honors and awards, including membership in the American Academy of Arts and Sciences and the Distinguished Service Award, the US Army’s highest decoration for a civilian.

In recent years, however, he was best known for his role in helping to design the US military’s current policy on gay personnel.

According to an obituary posted on the Michael D. Palm Center website:

Until the end of his life, Moskos was always willing to engage his colleagues in discussions of ideas, and he held steadfastly to his beliefs even when they were unpopular. According to Palm Center Director Aaron Belkin, “Charlie consistently defended the ‘don’t ask, don’t tell’ policy, but was also concerned about the effect it was having on gay and lesbian troops.” Scholars and activists on all sides of this issue were impressed over the years with Moskos’s ability to defend and critique the policy. In 2000, for instance, he called the effects of the policy “insidious” because gays and lesbians have sometimes been cowed into tolerating harassment because they were fearful that reporting it could bring them unwanted scrutiny.

Belkin added that, “Moskos operated in a tradition of practical sociology that affected people’s lives in tangible ways. His passion, intellect and good nature will be sorely missed.”

Palm Center Senior Research Fellow Nathaniel Frank’s review of Moskos’ role in the DADT debate can be found on their website.

Discussions of the social science data relevant to the DADT policy can be found in my 2006 post, “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” Redux, and in the Beyond Homophobia archives.

Copyright © 2008 by Gregory M. Herek. All rights reserved.

Permalink ·

December 12, 2007

Posted at 11:17 am (Pacific Time)

Pioneering gay historian Allan Bérubé died yesterday from complications related to stomach ulcers. He was 61. Allan wrote the award-winning book Coming Out Under Fire: The History of Gay Men and Women in World War II.

Here is the text of an obituary written by author Wayne Hoffman, Allan’s longtime friend:

Gay historian Allan Bérubé, award-winning author of Coming Out Under Fire, died on December 11, 2007. He was 61.

His death was due to sudden complications following the discovery of two stomach ulcers, according to his close friend Jonathan Ned Katz, a fellow gay historian.

Bérubé was, for decades, an independent historian and community activist. He first came to progressive political activism in opposition to the Vietnam war, working with the American Friends Service Committee in Boston in the late 1960s, after dropping out of the University of Chicago. After coming out in 1969, he joined a “gay liberation collective household,” and later moved to San Francisco to join a gay commune for craftspeople. He remained in San Francisco for many years, and was one of the founders of the San Francisco Lesbian and Gay History Project in 1978. His slide shows about women who dressed and passed as men – and married other women – were welcomed by enthusiastic audiences around the country.

Bérubé is best remembered for his groundbreaking work of gay history, published in 1990: Coming Out Under Fire: The History of Gay Men and Women in World War II. The Lambda Literary Award-winning book, which was later adapted by Arthur Dong into a Peabody Award-winning documentary, was often cited in Senate hearings on the military’s anti-gay policies in 1993.

Martin Duberman, distinguished professor of history emeritus at the City University of New York, called Bérubé’s book “superb…not only in terms of his prose style, which was absolutely lucid and even elegant, but also in terms of the very fine-spun analysis. Allan was not one to create shallow generalizations about either a given individual or a series of events. He was utterly meticulous and utterly careful. No one will ever, I think, have to redo the book on World War II, and you can almost never say that about a historian or a given piece of historical research.”

In 1996, Bérubé received a “genius grant” from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation for his work.

For the past decade, while living in New York City and the Catskills, Bérubé had been working on a history of queer working class men in the Marine Cooks and Stewards Union in the 1930s and ’40s, a project for which he received a Rockefeller Residency Fellowship in the Humanities from the Center for Lesbian and Gay Studies at CUNY.

Bérubé traveled the country presenting slide shows about his current research, and lectured on gay and lesbian history at Stanford University and the University of California, Santa Cruz. He wrote stories for numerous publications, including Mother Jones, Gay Community News, The Advocate, The Washington Blade, Out/Look, and the Body Politic. He also published articles in several anthologies, including White Trash (which included a rare personal essay in which he recounted his childhood in a trailer park in Bayonne, N.J.) and Policing Public Sex, in which he detailed the history of gay bathhouses.

“Allan took great pride in his role as a community historian,” said John D’Emilio, professor of history at the University of Illinois at Chicago and author of several books on gay history. “He loved the excitement that his talks and slide shows generated in an audience, and he loved that he, a college dropout, had written a book that made a difference in the world. He was an inspiration to everyone who knew him, as sweet and kind and genuinely moral a human being as anyone could hope to meet.”

For the past several years, Bérubé lived in Liberty, N.Y., in the Catskills. There, he owned a bed & breakfast, and operated Intelligent Design, a store selling mid-century modern collectibles. Berube’s partner, John Nelson, said, “Allan just loved it when people walked into the Liberty story, looked around, and were happy.”

Bérubé was twice elected a trustee of the village of Liberty.

“Allan was extremely proud of helping to preserve Liberty’s historic character,” said Katz. “Allan initiated the successful nomination of Liberty’s whole Main Street as a historic district, saved from demolition a major building with a classic 1950s façade, and bought and renovated the Shelburne Playhouse, one of the last remaining performance halls that were once part of the area’s many hotels.”

In addition to Nelson, Bérubé is also survived by his mother and three sisters.

I had the pleasure and privilege of knowing Allan and watching him complete the manuscript for Coming Out Under Fire. I can only echo John D’Emilio’s observation that Allan was an inspiration, and “as sweet and kind and genuinely moral a human being as anyone could hope to meet.”

Copyright © 2007 by Gregory M. Herek. All rights reserved.

Permalink ·

In the course of her remarkable life, Dr. Hooker surmounted many of the barriers faced by women who sought an academic career in the 20th century. She is best known for her psychological research in the 1950s and 1960s with gay men.

In the course of her remarkable life, Dr. Hooker surmounted many of the barriers faced by women who sought an academic career in the 20th century. She is best known for her psychological research in the 1950s and 1960s with gay men.